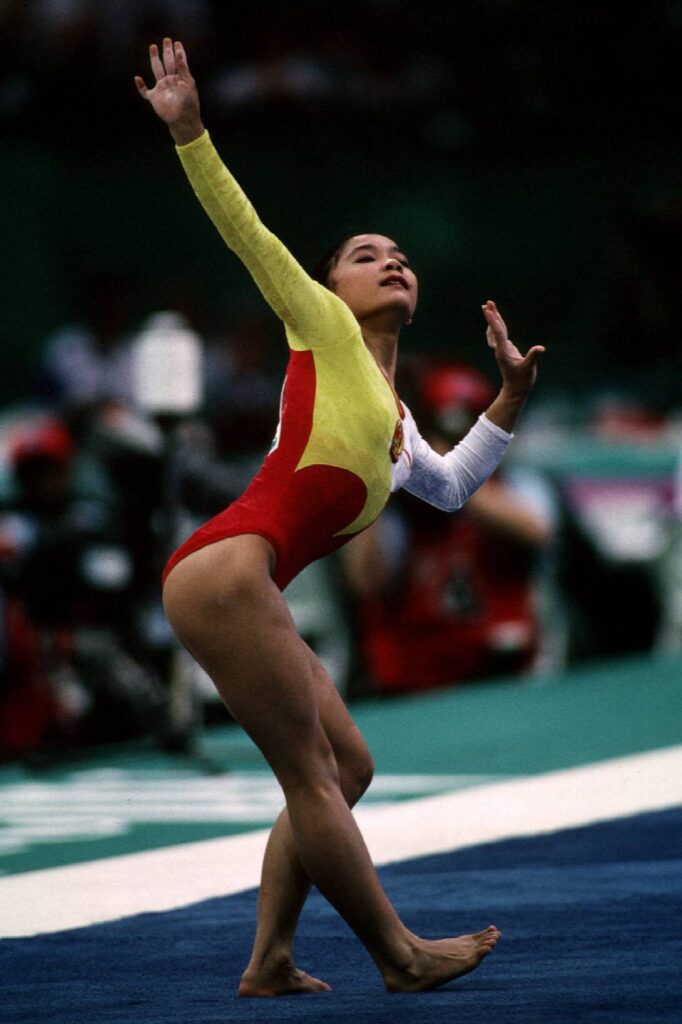

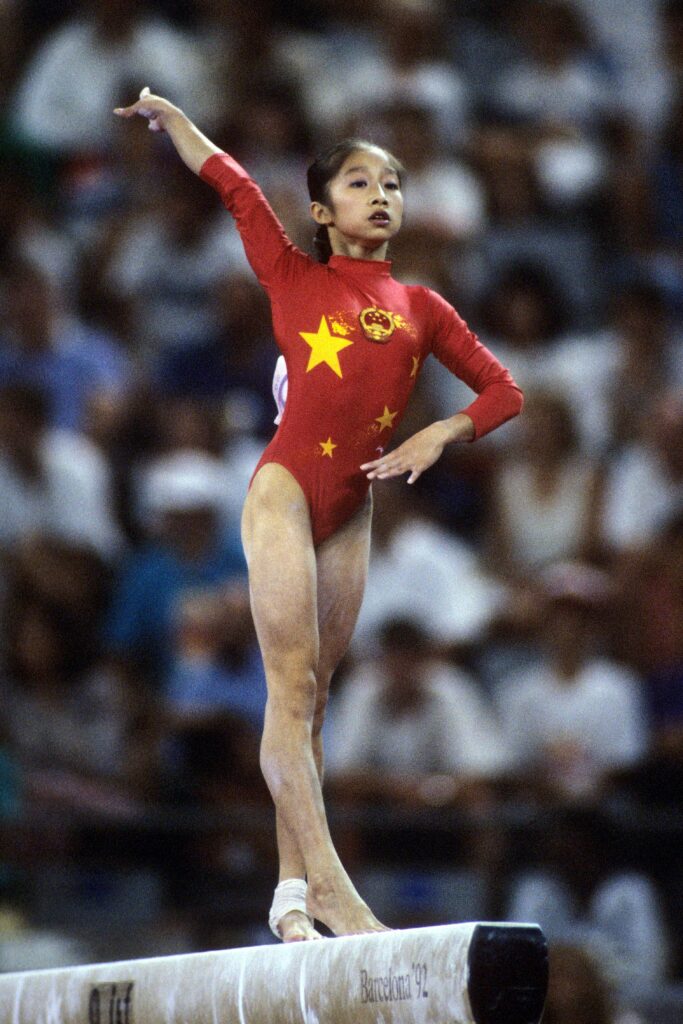

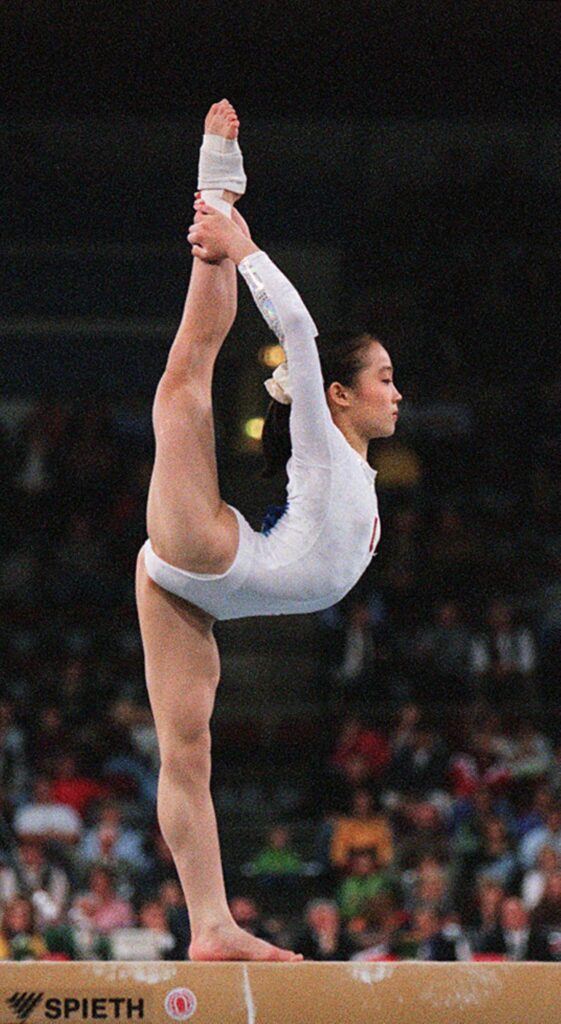

In Gymnastics’ Greatest Stars, Kathy Johnson introduced American audiences to a rising Chinese gymnast:

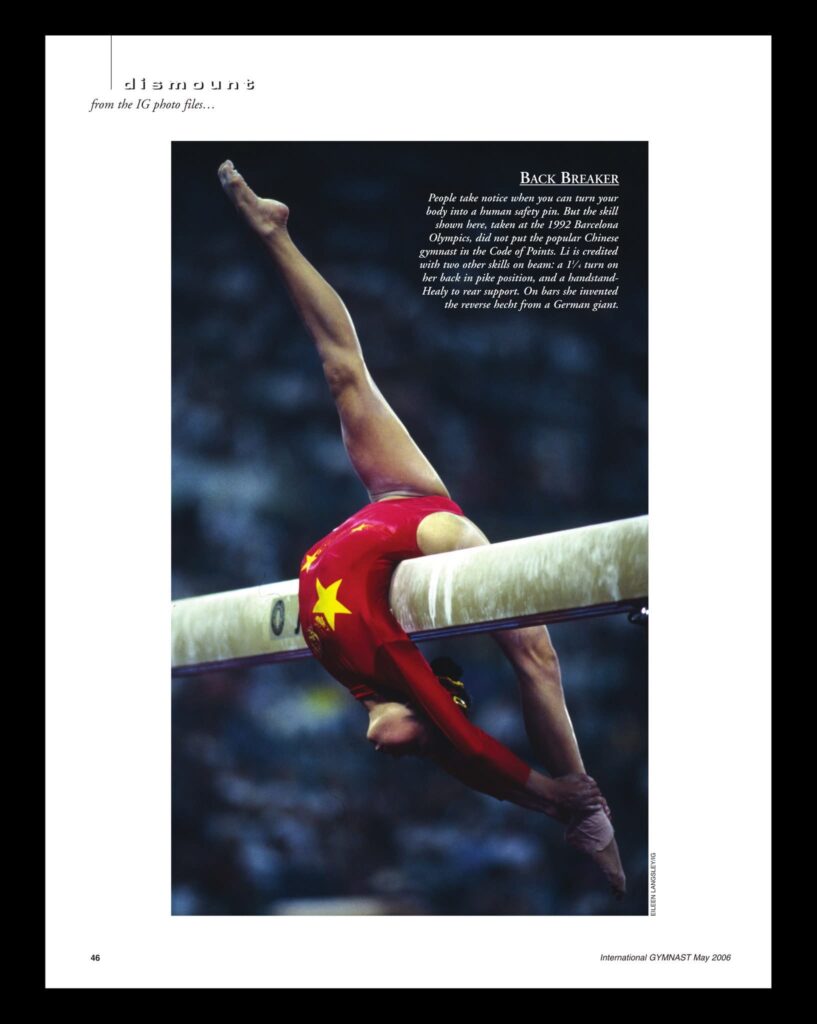

“Her name is Yang Bo, and in Chinese, Bo means waves, which is exactly what she made at the ’89 Worlds with this move on the beam. She is one of the fresh new faces who has pushed the Chinese women back into the top three.”

The move Johnson was describing was a layout step-out directly into a high Rulfová—one of the most breathtaking combinations ever performed on balance beam.

Yang Bo has long since earned her place in the pantheon of great beam workers. But there is one small complication. She should not have been at the 1989 World Championships at all.

Officially, Yang Bo competed with a 1973 birthdate. In reality, she appears to have been born in 1975, according to her profile on the Beijing Sport University website. That would have made her just fourteen in Stuttgart.

In other words, one of the most celebrated beam routines of the late 1980s may also have been performed by an underage gymnast.

And in a twist that feels almost ironic, Yang Bo herself never particularly loved the sport. As she reflected years later:

“Choosing gymnastics was not really my decision. I didn’t actually love gymnastics—I just happened to be good at it. After becoming an athlete, I sometimes wanted to quit, but my parents told me to persevere.”

Her real passion, it turned out, was singing.

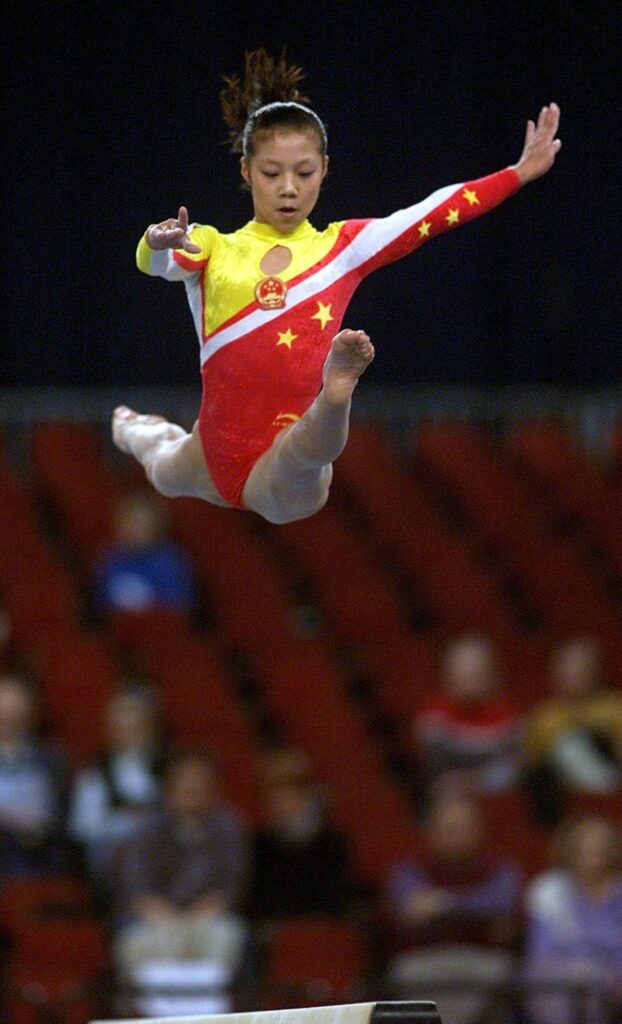

The article below—published in 2007 by Bund Pictorial—captures Yang Bo years after her gymnastics career ended, as she attempted to reinvent herself on an entirely different stage.

Note: The interview itself appears to assume a 1974 birth year, while Yang Bo’s Beijing Sport University profile lists 1975.