By 1967, Miroslav Cerar had been a major player on the international gymnastics scene for nearly a decade. His first major international competition was the 1958 World Championships in Moscow, where he finished thirteenth in the all-around and third on pommel horse. He was 18 at the time, and as the 1960s progressed, he watched as many of his fellow competitors retired from the sport. In 1967, he was the last of the men’s artistic medalists from the 1958 World Championships to continue competing.

What follows is a translation of an interview that ran in Stadión, a weekly Czechoslovak sports magazine.

Note: The Mohicans were an indigenous tribe from the area that the present-day United States occupy. The title of this article comes from James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel by the same name, the last line of which is, “I have lived to see the last warrior of the wise race of the Mohicans,” referring to Chingachgook. Nowadays, the phrase “the last of the Mohicans” refers to the last survivor of a noble race. I recognize that it’s problematic to call a white European the “last of the Mohicans,” but I can’t go back and change the title of the piece.

The Last of the Mohicans

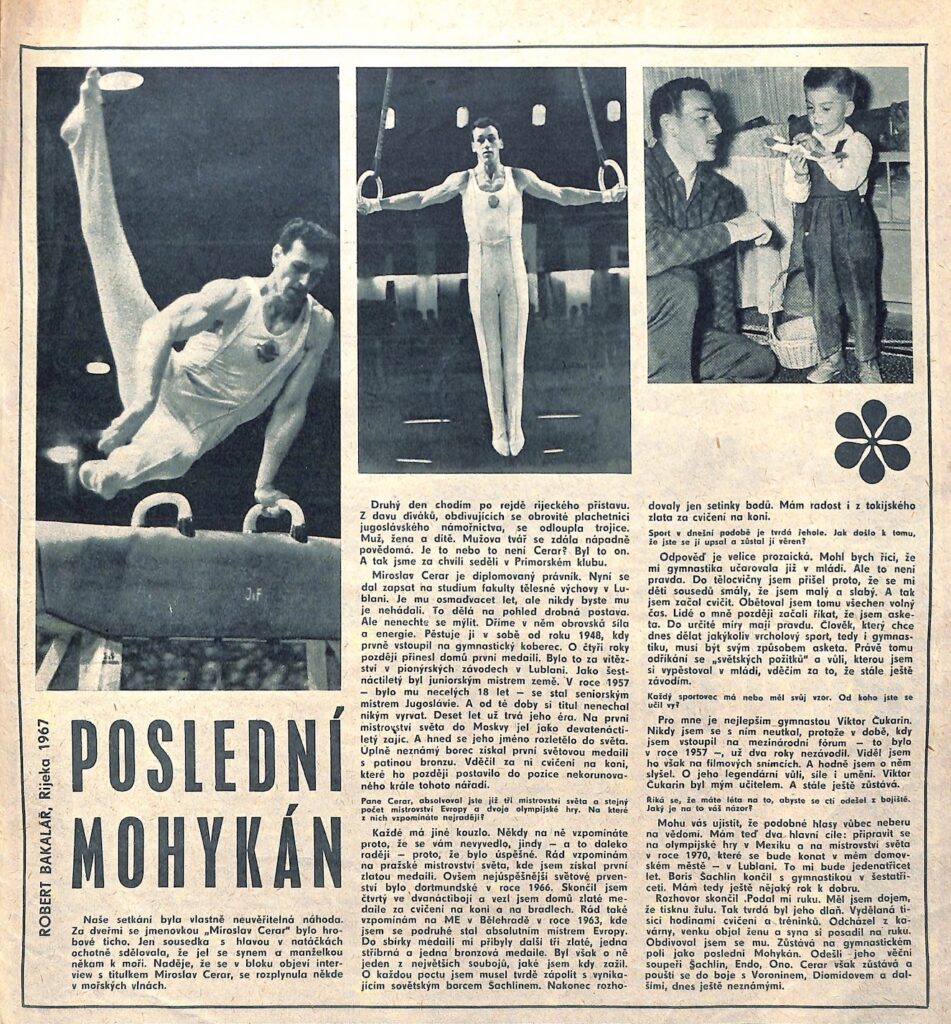

Our meeting was actually an incredible coincidence. Behind the door with the name tag “Miroslav Cerar,” there was a grave silence; only the neighbor with her head in the curlers willingly told us that he had gone with his son and his wife somewhere to the sea. The hope that an interview with the headline Miroslav Cerar would appear in the notepad had vanished somewhere in the sea waves.

The next day I walk along the waterfront of the port of Rijeka. From the crowd of onlookers admiring the huge sailing ship of the Yugoslav navy, a trio peeled off, a man, a woman and a child. The man’s face looked strikingly familiar. Is it or is it not Cerar? It was him. And so, we soon were sitting in the Primorsky Club.

Miroslav Cerar is a graduated lawyer. He has now enrolled at the Faculty of Physical Education in Ljubljana. He’s twenty-eight years old, but you’d never guess it. That’s what a slight figure makes you look like. But make no mistake. There’s tremendous strength and energy in him. He’s been cultivating the strength since 1948, when he first stepped onto the gymnastics carpet. Four years later, he brought home his first medal. It was for winning the pioneer competition in Ljubljana. At the age of 16, he was the junior national champion. In 1957 – he was just 18 years old – he became the champion of Yugoslavia in the senior category. And he hasn’t let anyone snatch the title from him since. His era has lasted ten years already. He went to his first world championship in Moscow as a 19-year-old spring chicken.* And immediately his name was heard all around the world. A complete unknown won the world’s first medal with the patina of bronze. He owed it to his training on the horse, which later made him the uncrowned king of this apparatus.

[*Note: Cerar turned 19 in 1958, but at the time of the Moscow World Championships, he was still 18.]

Mr. Cerar, you have already attended three World Championships and the same number of European Championships and two Olympic Games. Which of them are your favorite memories?

Each has a different charm. Sometimes you remember them because they didn’t work out, sometimes — and much more preferably — because they were successful. I like to remember the World Championships in Prague, where I won my first gold medal. But the most successful world championship was Dortmund in 1966. I finished fourth in the 12-discipline fight [i.e. the all-around] and took home gold medals for the pommel horse and the parallel bars. I also fondly remember the 1963 European Championships in Belgrade, where I became the overall European champion for the second time. I added three more golds, one silver, and one bronze medals to my medal collection. However, it was one of the greatest battles I have ever experienced. I had to fight hard for every honor with the outstanding Soviet fighter Shakhlin. In the end, only hundredths of points were decisive. I’m also happy about the Tokyo gold for pommel horse.

Sport, as we know it today, is hard work. How did it come about that you signed up for it and stayed true to it?

The answer is very prosaic. I could say that I was enchanted by gymnastics at a young age. But that’s not true. I came to the gym because the neighbors’ kids laughed at me for being small and weak. And so I started working out. I devoted all my free time to it. Later, people started calling me an ascetic. To a certain extent, they’re right. Anyone who wants to do any top sport today, including gymnastics, has to be an ascetic in a way. It’s that renunciation. It is to this renunciation of “worldly pleasures” and the will I developed in my youth that I owe the fact that I am still competing.

Every athlete has or had a role model. Whom did you learn from?

For me, the best gymnast is Viktor Chukarin. I never met him because by the time I joined the International Forum — that was in 1957 — he hadn’t competed for two years. But I have seen him on film. And I heard a lot about him. About his legendary will, his strength and his art. Viktor Chukarin was my teacher. And he still is.

They say you have reached the age to leave the battlefield with honor. What’s your opinion on that?

I can assure you that I do not take note of such voices at all. I now have two main goals: to prepare for the Olympic Games in Mexico and for the 1970 World Championships, which will be held in my hometown, Ljubljana. I will be thirty-one years old by then. Boris Shakhlin quit gymnastics at thirty-six. So I still have a few years to go.

The interview ended. He shook my hand. I felt like I was squeezing granite, so hard was his palm. Earned through thousands of hours of practice and training. He left the cafe, hugged his wife outside, and sat his son on his hand. I admired him. He remains on the gymnastic field as the last of the Mohicans. Gone are his eternal rivals, Shakhlin, Endo, Ono. But Cerar remains and takes on Voronin, Diomidov and others, now still unknown.

Stadión, 14 September 1967

Poslední Mohykán

Naše setkání byla vlastně neuvěřitelná náhoda. Za dveřmi se jmenovkou „Miroslav Cerar“ bylo hrobové ticho, Jen sousedka s hlavou v natáčkách ochotně sdělovala, že jel se synem a manželkou někam k moři. Naděje, že se v bloku objeví interview s titulkem Miroslav Cerar, se rozplynula někde v mořských vlnách.

Druhý den chodím po rejdě rijeckého přístavu. Z davu diváků, obdivujících se obrovité plachetnici jugoslávského námořnictva, se odloupla trojice, Muž, žena a dítě. Mužova tvář se zdála nápadně povědomá. Je to nebo to není Cerar? Byl to on. A tak jsme za chvíli seděli v Primorském klubu.

Miroslav Cerar je diplomovaný právník. Nyní se dal zapsat na studium fakulty tělesné výchovy v Lublaní. Je mu osmadvacet let, ale nikdy byste mu je nehádali. To dělá na pohled drobná postava. Ale nenechte se mýlit. Dříme v něm obrovská síla a energie. Pěstuje ji v sobě od roku 1948, kdy prvně vstoupil na gymnastický koberec. O čtyři roky později přinesl domů první medaili. Bylo to za vítězství v pionýrských závodech v Lublani. Jako šestnáctiletý byl juniorským mistrem země. V roce 1957 — bylo mu necelých 18 let — se stal seniorským mistrem Jugoslávie. A od té doby si titul nenechal nikým vyrvat. Deset let už trvá jeho éra. Na první mistrovství světa do Moskvy jel jako devatenáctiletý zajíc. A hned se jeho jméno rozletělo do světa. Úplně neznámý borec získal první světovou medaili s patinou bronzu. Vděčil za ni cvičení na koni, které ho později postavilo do pozice nekorunovaného krále tohoto nářadí.

Pane Cerar, absolvoval jste již tři. mistrovství světa a stejný počet mistrovství Evropy a dvoje olympijské hry. Na které z nich vzpomínáte nejraději?

Každé má jiné kouzlo. Někdy na ně vzpomínáte proto, že se vám nevyvedlo, jindy — a to daleko raději — proto, že bylo úspěšné. Rád vzpomínám na pražské mistrovství světa, kde jsem získal první zlatou medaili. Ovšem nejúspěšnější světové prvenství bylo, dortmundské v. roce. 1966. Skončil jsem čtvrtý ve dvanáctiboji a vezl jsem domů zlaté medaile za cvičení na koni a na bradlech. Rád také vzpomínám na ME v Bělehradě v roce 1963, kde jsem se podruhé stal absolutním mistrem Evropy. Do sbírky medailí mi přibyly další tři zlaté, jedna stříbrná a jedna bronzová medaile. Byl však o ně jeden z největších soubojů, jaké jsem kdy zažil. O každou poctu jsem musel tvrdě zápolit s vynikajícím sovětským borcem Šachlinem. Nakonec rozhodovaly jen setinky bodů. Mám radost i z tokijského zlata za cvičení na koni.

Sport v dnešní podobě je tvrdá řehole. Jak došlo k tomu, že jste se ji upsal a zůstal jí věren?

Odpověď je velice prozaická. Mohl bych říci, že mi gymnastika učarovala již v mládí. Ale to není pravda. Do tělocvičny jsem přišel proto, že se mi děti sousedů smály, že jsem malý a slabý. A tak jsem začal cvičit. Obětoval jsem tomu všechen volný čas. Lidé o mně později začali říkat, že jsem asketa. Do určité míry mají pravdu. Člověk, který chce dnes dělat jakýkoliv vrcholový sport, tedy i gymnastiku, musí být svým způsobem asketa. Právě tomu odříkání se. „světských požitků“ a vůli, kterou jsem si vypěstoval v mládí, vděčím za to, že stále ještě závodím.

Každý sportovec má nebo měl svůj vzor. Od koho jste se učil vy?

Pro mne je nejlepším gymnastou Viktor Čukarin. Nikdy jsem se s ním neutkal, protože v době, kdy jsem vstoupil na mezinárodní fórum — to bylo v roce 1957 —, už dva roky nezávodil. Viděl jsem ho však na filmových snímcích. A hodně jsem o něm slyšel. O jeho legendární vůli, síle i umění. Viktor Čukarin byl mým učitelem. A stále ještě zůstává. Říká se, že máte léta na to, abyste se ctí odešel r bojiště.

Říká se, že máte léta na to, abyste se ctí odešel z bojiště. Jaký je na to váš názor?

Mohu, vás ujistit, že podobné hlasy vůbec neberu na vědomí. Mám teď dva hlavní cíle: připravit se na olympijské hry v Mexiku a na mistrovství světa v roce 1970, které se bude konat v mém domovském městě — v Lublani. To mi bude jedenatřicet let. Boris Šachlin končil s gymnastikou v šestatřiceti. Mám tedy ještě nějaký rok k dobru.

Rozhovor skončil „Podal mi ruku. Měl jsem dojem, že tisknu žulu, Tak tvrdá byl jeho dlaň. Vydělaná tisíci hodinami cvičení a tréninků. Odcházel z kavárny, venku objal ženu a syna si posadil na ruku. Obdivoval jsem se mu. Zůstává na gymnastickém poli jako poslední Mohykán. Odešli jeho věční soupeři Šachlin, Endo, Ono. Cerar však zůstává a pouští se do boje s Voroninem, Diomidovem a dalšími, dnes ještě neznámými.

Note: Cerar did not continue to compete until he was 36 like Shakhlin. His last major competition was in 1970 in Ljubljana.

One reply on “1967: Miroslav Cerar, The Last of the Greats”

He is one of the nicest persons you could ever meet.