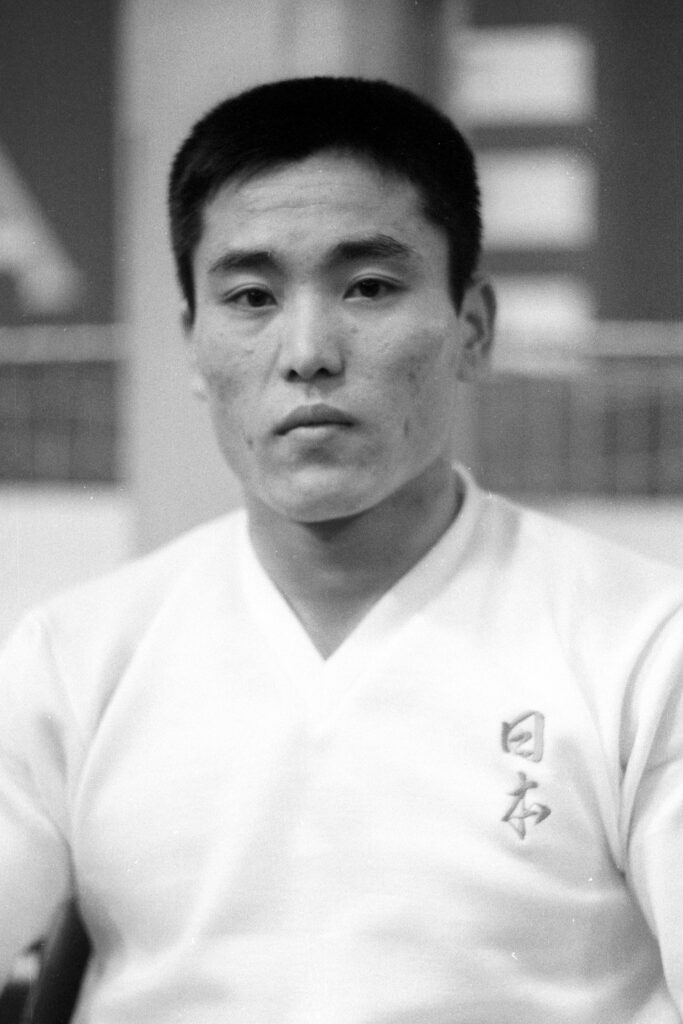

The 1970 World Championships were a pivotal moment in the history of gymnastics. Men’s vault was considered boring in the late 1960s. But that changed at the 1970 World Championships when Tsukahara unveiled his namesake vault. The crowd loved it. In fact, during the optionals portion of the World Championships, the crowd protested Tsukahara’s 9.75.

Note: If you want to be extremely pretentious, you can call a “Tsukahara” a “Tivoli Vault.” Reportedly, that’s what Tsukahara was going to name the vault.

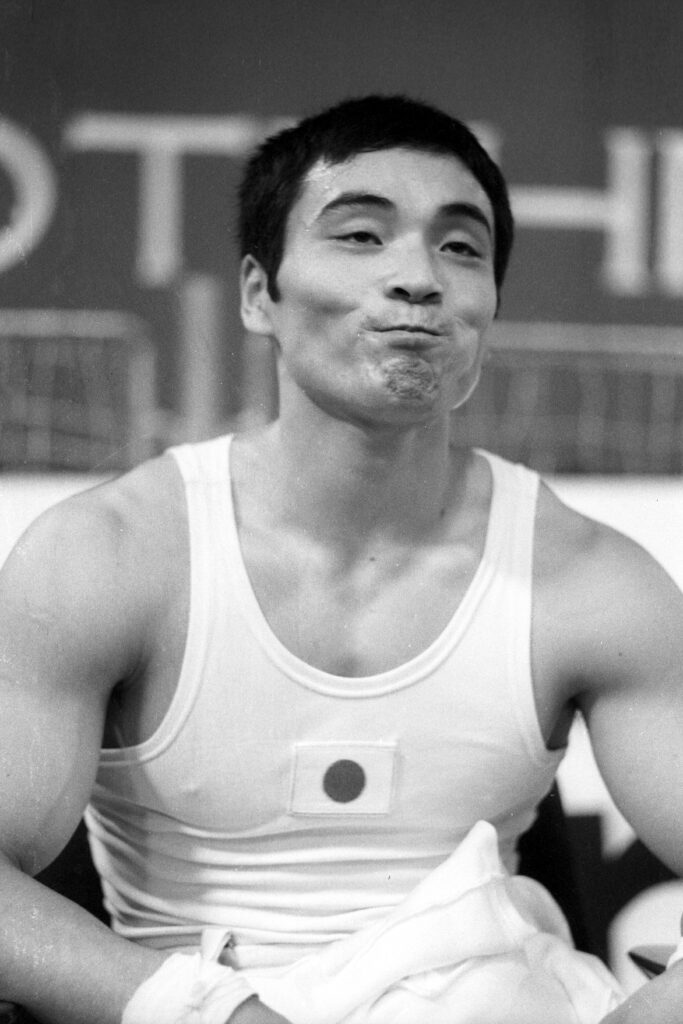

In addition to the debut of the Tsukahara vault, Kenmotsu, the 1970 World All-Around Champion, attempted a triple twist on floor. After the 1968 Olympics, he spent two years trying to personalize his gymnastics. It’s debatable whether or not he achieved his goal. Endo, Japan’s head coach at the time, bluntly said, “What sets Kenmotsu apart from others? I do not know very well.” Ouch.

Here’s what else happened at the 1970 World Championships…

The Basics | Historical Context | Gymnastics Context | Pre-Competition Chatter | Video | Team | All-Around | Event Finals | Additional Quotes

The Basics

Location: Ljubljana, Yugoslavia

Opening Ceremony: Thursday, October 22, 1970

MAG Compulsories: Saturday, October 24, 1970

MAG Optionals: Monday, October 26, 1970

Event Finals: Tuesday, October 27, 1970

Historical Context

- Apollo 13 launched on April 11. On April 13, an oxygen tank exploded, leading to the sentence: “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”

- In March, Japanese Red Army members hijacked Japan Airlines Flight 351.

- Dan-Air Flight 1903 destined for Barcelona crashed, killing all 112 people on board.

- The Moscow Treaty was signed by the Soviet Union and West Germany in 1970. The two countries pledged non-aggression.

- In 1970, East Germany abandoned its Economic System of Socialism (ESS), in which the country invested heavily in industries like electronics, chemicals, and plastics with the hope of exporting these products and leaping ahead of western countries.

Other cultural touchpoints in 1970:

- Billboard’s top song of 1970 was “Bridge over Troubled Water” by Simon and Garfunkel

- The Academy Award for Best Picture went to Midnight Cowboy.

- The Beatles released Let It Be, and, shortly thereafter, Paul McCartney announced that he was leaving the group.

- Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, and Janis Joplin died of overdoses.

- Mitsubishi Motors was founded.

Gymnastics Context

- Reigning World Champions (1966)

- Team: Japan*

- All-Around: Mikhail Voronin

- Floor: Nakayama Akinori*

- Pommel Horse: Miroslav Cerar*

- Rings: Mikhail Voronin

- Vault: Matsuda Haruhiro

- Parallel Bars: Sergei Diomidov

- High Bar: Nakayama Akinori

* indicates that the World Champion in 1966 successfully defended his title in 1970

- Reigning Olympic Champions (1968)

- Team: Japan**

- All-Around: Kato Sawao

- Floor: Kato Sawao

- Pommel Horse: Miroslav Cerar**

- Rings: Nakayama Akinori**

- Vault: Mikhail Voronin

- Parallel Bars: Nakayama Akinori**

- High Bar: Mikhail Voronin and Nakayama Akinori

** indicates that the reigning Olympic champion was victorious again at the 1970 Worlds

- All-Around Results of the European Championships (1969)

- 1st: Mikhail Voronin

- 2nd: Viktor Klimenko

- 3rd: Mikołaj Kubica

- University Games Champion (1970): Okamura Terumichi

- Reminder: There was supposed to be a qualifications process for the 1970 World Championships, but it fell through due to politics. More here.

Chatter before the Competition

On Voronin and Kato, the 1968 All-Around Stars

Mikhail Voronin reportedly wasn’t in good shape, but he wouldn’t have to compete against his rival Kato Sawao, who suffered an Achilles injury earlier in the year.

Mikhail Voronin, who, according to the scant reports that trickle down from Moscow, seems to be in poor shape. In any case, the competition with Kato Sawao — who beat him at the Olympic Games in Mexico with a difference of only five hundredths of a point, keeping him from the gold — is not to be feared. The Japanese suffered an Achilles tendon injury at the beginning of this year, which left him with a huge training delay. Kato still tried, but after the qualifying matches from the Japanese federation, he was told: “Jappari dame,” which means as much as: “It’s not working.” Nevertheless, despite the lack of Kato and Endo Yukio, who retired after Mexico, the Japanese are strong favorites for the team championship.

Tubantia, Oct. 23, 1970

Michael Voronin, die volgens de schaarse berichten, welke uit Moskou doordruppelen, in een voortret’ lelijke vorm schijnt te steken, hoeft in elk geval de concurrentie van Sawao Kato, die hem bij de Olympische spelen van Mexico met een verschil van slechts vijfhonderdste punt van het goud afhield niet te vrezen. De Japanner liep begin van dit jaar een achillespeesblessure op, die hem een enorme trainingsachterstand opleverde. Kato probeerde het nog wel, maar kreeg na de kwalificatiewedstrijden van de Japanse bond te horen: „Jappari dame”, wat zoveel betekent als: „Het gaat niet”. Toch zijn de Japanners, ondanks het gemis van Kato en Yukio Endo, die na Mexico stopte, i sterk favoriet voor het ploegenkampioenschap.

More on Kato’s Achilles tear here.

The North Koreans

The Swiss newspaper L’Express was eagerly awaiting the participation of the North Koreans.

At first glance, one might think that we have made up our time again to get to the front row. In reality, the situation is a bit different. Let’s see what the forces are. At the top of the table we find Olympic winner Japan and the USSR, which are practically untouchable. We will recall that if the gap, however significant, separating the Japanese from the Soviets was 4.80 points in Mexico, that separating them from the East Germans was 13.95 points! This means that the difference of class is enormous.

But, in Ljubljana, a new factor will be inserted in this hierarchy: among the 23 countries which will compete by team, we will find the North Koreans. They are able to achieve the poker stroke that their fellow footballers had achieved in England where they eliminated the “squadra azzurra.” The Koreans, in the opinion of Bulgarian specialists, who visited them, do not train less than eight hours a day, at the rate of five practices per week, and, when one knows their natural gifts, one can be certain that their participation “will hurt.” From there, we will have, in our opinion, a peloton comprising the United States, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Switzerland fighting for 5th place.

L’Express, Oct. 22, 1970

A première vue, on pourrait croire que nous avons refait notre retard pour nous hisser aux premières loges. En réalité, la situation est un peu autrement. Voyons quelles sont les forces en présence. En haut du tableau, nous trouvons le Japon, vainqueur olympique, et l’URSS, qui sont pratiquement intouchables. On se rappellera que si l’écart, pourtant important, séparant les Nippons des Soviétiques était de 4,80 p. a Mexico, celui séparant ceux-ci des Allemands de l’Est était de 13,95 p. ! C’est dire que la différence de classe est énorme.

Mais, à Ljubljana, un nouveau facteur viendra s’intercaler dans cette hiérarchie : parmi les 23 pays qui concourront par équipe, nous trouverons les Coréens du Nord. Ils sont capables de réaliser le coup de poker que leurs confrères footballeurs avaient réussi en Angleterre où ils éliminèrent la « squadra azzurra ». Les Coréens, de l’avis de spécialistes bulgares, qui les visitèrent, ne s’entraînent pas moins de huit heures par jour, à raison de cinq entraînements par semaine et, lorsqu’on connaît leurs dons naturels, on peut être certain que leur entrée « fera mal ». Dès lors, on aura, à notre avis, un peloton comprenant, les Etats-Unis, la Tchécoslovaquie, la Pologne et la Suisse luttant pour la 5me place.

But the North Korean team did not end up participating.

North Korea will not participate in the World Artistic Gymnastics Championships in Ljubljana: This decision has been communicated to the International Gymnastics Federation by telegraph and without an explanation. North Korea’s men’s team was the favorite for the bronze.

Tubantia, Oct. 23, 1970

Noord-Korea zal niet deelnemen ‘ aan de wereldkampioenschappen turnen in Ljubljana: Dit besluit is telegrafisch en zonder opgave van reden aan de internationale turnbond ter kennis gebracht. Het herenteam van Noord-Korea gold als favoriet voor het brons.

The Dutch Team

The public was questioning if the Dutch should even compete since they had no chance at medals. The gymnasts were going for the experience and to see what other top teams are doing.

Cor Smulders, the national champion, says it in all sincerity, “The sole aim is to exceed our personal achievements. Gaining as much competition experience as possible and discovering what, for example, the Japanese and Russians perform are the main arguments why we should be represented in this world championship. For us, it’s just important to learn to have even more control, to flip as strong as possible.”

De tijd, Oct. 23, 1970

Cor Smulders, de nationale kampioen, zegt het in alle oprechtheid „Het is uitsluitend de bedoeling, onze persoonlijke prestaties te overtreffen Het opdoen van zoveel mogelijk wedstrijdervaring en het ontdekken van wat bijvoorbeeld de Japanners en de Russen laten zien zijn de voornaamste argumenten, waarom wij in dit wereld gezelschap vertegenwoordigd horen te zijn. Voor ons is gewoon belangrijk nog meer beheersing te leren opbrengen, om zo sterk mogelijk te draaien.”

The Italian Team

During the University Games, Franco Menichelli complained about the state of gymnastics in Italy.

The Olympian Menichelli, who assists the Italian team as a coach (Pallottl, Vallatl, Tornassi, and Mori) does not hide a certain bitterness: “We are sorry -—he said — to see that the other nations progress continuously and we, instead, we go back. We are doing a good job at the base but it is necessary that they give us the means for proper preparation. Hopefully, in a few years, we will be able to present some champions too. Otherwise we can close the doors and dedicate ourselves to other activities “

La Stampa, Sept. 2, 1970

L’olimpionico Menichelli, che assiste come allenatore la squadra azzurra (Pallottl, Vallatl, Tornassi e Mori) non nasconde una certa amarezza: «Dispiace — ha affermato — vedere che le altre nazioni progrediscono continuamente e noi, invece, torniamo Indietro. Stiamo facendo un buon lavoro alla base ma è necessario che ci diano 1 mezzi per una preparazione adeguata. Se tutto andrà bene, fra qualche anno saremo in grado di presentare anche noi qualche campioni. In caso contrario possiamo chiudere i battenti e dedicarci ad altre attività».

Video Footage

It’s difficult to identify many of the gymnasts in this grainy footage. But the big deal was Tsukahara’s new vault:

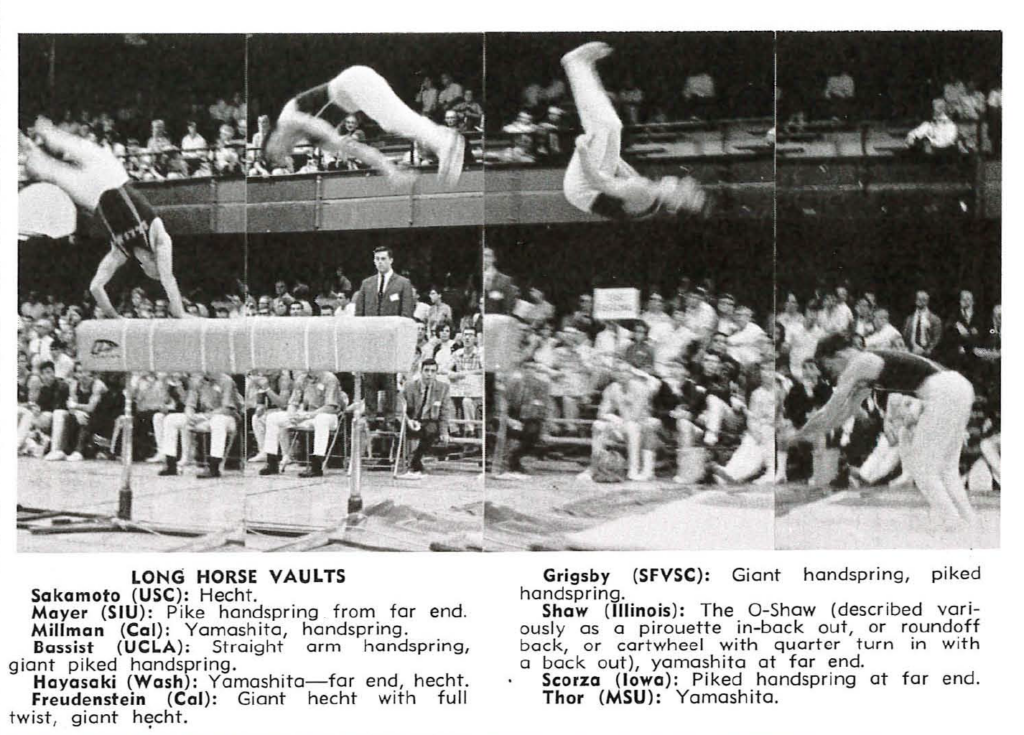

Reminder #1: The U.S. gymnast Hal Shaw performed a Tsukahara vault at the 1968 NCAA Championships. Nationally, it was called the “O-Shaw.”

Reminder #2: There’s a handspring front in the video above. It wasn’t the first vault of its kind in international competition. Okamura Terumichi, for example, had performed a handspring front tuck at the University Games in September (Modern Gymast, October 1970).

Other skills performed in addition to the Tsukahara vault:

1. Straddle out of Germans as you reach the top of the bar.

Source: Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1970

2. Whippit on rings — Back uprise front somersault to an “L” position rotating rings rather than releasing them.

3. Stem upstart on rings.

4. Five double backs on floor.

5. Triple twister on floor. [Performed by Kenmotsu of Japan]

6. Double twister off rings.

7. 3/2 twisting front off rings.

8. On high bar deep piked front with a delayed 1/2 twist.

9. Full twisting stutz.

Team Competition

Reminder: There wasn’t a separate team final. The team rankings were determined based on the compulsory and optionals portions of the competition.

| Country | FX | PH | SR | VT | PB | HB | Total |

| 1. JPN | 571.10 | ||||||

| Comp. | 47.25 | 46.40 | 47.00 | 47.45 | 48.00 | 48.00 | 284.10 |

| Opt. | 47.25 | 47.15 | 48.25 | 47.40 | 48.40 | 48.55 | 287.00 |

| 2. URS | 564.35 | ||||||

| Comp. | 46.20 | 46.35 | 46.15 | 46.30 | 47.90 | 46.95 | 279.85 |

| Opt. | 47.25 | 47.50 | 47.50 | 46.70 | 47.85 | 47.70 | 284.50 |

| 3. GDR | 553.15 | ||||||

| Comp. | 45.30 | 45.85 | 44.95 | 45.70 | 46.30 | 47.20 | 275.30 |

| Opt. | 45.55 | 46.25 | 45.95 | 46.30 | 46.15 | 47.65 | 277.85 |

| 4. YUG | 549.45 | ||||||

| Comp. | 44.40 | 46.35 | 44.05 | 44.95 | 46.60 | 46.00 | 272.35 |

| Opt. | 45.80 | 46.80 | 45.10 | 45.75 | 46.75 | 46.90 | 277.10 |

| 5. POL | 547.05 | ||||||

| Comp. | 44.70 | 45.60 | 45.25 | 43.75 | 46.45 | 45.55 | 271.30 |

| Opt. | 45.55 | 46.40 | 45.90 | 45.45 | 46.25 | 46.20 | 275.75 |

| 6. SUI | 541.75 | ||||||

| Comp. | 44.50 | 43.90 | 43.40 | 44.85 | 46.30 | 46.05 | 269.00 |

| Opt. | 44.75 | 45.30 | 45.10 | 45.20 | 45.60 | 46.80 | 272.75 |

| 7. USA | 537.60 | ||||||

| Comp. | 44.65 | 44.70 | 42.95 | 42.45 | 45.05 | 45.65 | 265.45 |

| Opt. | 45.75 | 43.95 | 44.80 | 45.10 | 45.05 | 47.50 | 272.15 |

| 8. ROU | 536.55 | ||||||

| Comp. | 43.85 | 43.75 | 41.55 | 45.15 | 44.65 | 45.45 | 264.40 |

| Opt. | 45.50 | 44.80 | 43.70 | 46.35 | 45.25 | 46.55 | 272.15 |

| 9. TCH | 536.15 | ||||||

| Comp. | 43.45 | 44.05 | 41.80 | 43.50 | 45.70 | 45.55 | 264.05 |

| Opt. | 44.80 | 45.00 | 44.45 | 45.60 | 46.20 | 46.05 | 272.10 |

| 10. FRG | 532.45 | ||||||

| Comp. | 43.25 | 44.60 | 42.30 | 43.10 | 45.55 | 43.75 | 262.55 |

| Opt. | 43.45 | 45.80 | 44.55 | 44.25 | 45.75 | 46.10 | 269.90 |

11. Hungary 528.60

12. France 524.60

13. Bulgaria 523.95

14. Finland 519.15

15. Italy 515.25

16. Spain 511.60

17. Great Britain 502.80

18. Norway 500.15

19. Canada 498.10

20. Cuba 491.40

21. Israel 468.20

22. Austria 460.30

Japan

Endo expected more of the Japanese team.

“If it had been any other way, my team would have simply failed. The only question for me was who would win the individual championship: Kenmotsu Eizo or Nakayama Akinori. I have to disappoint anyone who might think that I am now 100 percent satisfied. It could have been even better. The boys can do much more on vault than they have shown here. And vault wasn’t quite to my liking either. When we get home, we’ll work hard on that. More strength needs to be developed on this part.”

De tijd, October 27, 1970

„Als het anders was galopen zou mijn ploeg gewoon hebben gefaald. Het was voor mij alleen de vraag, wie het persoonlijke kampioenschap zou behalen: Eizo Kenmotsu of Akinori Nakayama. Wie mocht denken dat ik nu voor 100 procent tevreden ben moet ik teleurstellen. Het had nog beter gekund. Bij het paardvoltigeren kunnen de jongens veel meer dan zij hier hebben laten zien. En het paardspringen ging ook niet helemaal naar mijn zin. Als we thuis zijn zullen we daar eens flink aan werken. Er moet op dit onderdeed meer kracht worden ontwikkeld.”

The hyped battle between Japan and the Soviet Union never materialized.

The expected duel between the gymnasts of Japan and the USSR did not take place. The team of the USSR was unable to make up for the failures of their top gymnasts on individual pieces of equipment.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 26, 1970

Das erwartete Duell zwischen den Turnern Japans und der UdSSR fand nicht statt. Die Mannschaft der UdSSR vermochte es nicht, Versager ihrer Spitzenturner an einzelnen Geräten wettzumachen.

In the absence of a dramatic finish, spectators had to appreciate the consistency of the Japanese.

If the fight for the team and individual all-around titles no longer had the touch of drama that characterized the previous day (when the dispute between the Soviet gymnasts and those from the GDR reached moments of unprecedented tension [during women’s compulsories]), it was interesting, instead, to watch the constancy, like a metronome, with which the Japanese went to the top of the world hierarchy, confirming, once again, their high class.

Sportul, Oct. 27, 1970

Dacă lupta pentru titlul pe echipe și la individual compus n-a mai avut nota de dramatism ce a caracterizat ziua precedentă (când disputa dintre gimnastele sovietice și cele din R.D.G. a atins momente de nemaiîntâlnită tensiune), a fost interesantă, în schimb, de urmărit constanța, de metronom, cu care japonezii s-au îndreptat spre vîrful ierarhiei mondiale, ei confirmînd, încă o dată, înalta lor clasă.

East Germany

The East Germans survived compulsory pommel horse.

Then the executioner of the gymnasts, the pommel horse. The team didn’t fail. Nevertheless, Klaus Köste remained below his possibilities with 9.05, but Peter Kunze rose to the same score. 45.85 on this apparatus — that wasn’t too bad either. The highest score, however, so far is only 9.40, hardly sufficient for the final.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 26, 1970

Dann der Scharfrichter der Turner, das Seitpferd. Die Mannschaft versagte nicht. Dennoch, Klaus Köste blieb mit 9,05 unter seinen Möglichkeiten, doch Peter Kunze steigerte sich auf die gleiche Note. 45,85 an diesem Gerät — auch das ließ sich nicht schlecht an. Die höchste Note aber bisher nur 9,40, für das Finale kaum ausreichend.

Compulsory parallel bars were more of a struggle.

On the parallel bars, the motto “Exercise calmly — don’t let yourself get nervous” brought us into dire straits. Here our squad would certainly have looked better with verve and vigor. The 46.30 was far below our possibilities.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 26, 1970

Am Barren brachte uns die ausgegebene Devise “Ruhig turnen — nicht nervös machen lassen” in arge Bedrängnis. Hier hätte unsere Riege mit Schwung und Elan sicher besser ausgesehen. Die 46,30 waren weit unter unseren Möglichkeiten.

But the Romanian press thought that the East Germans looked strong during compulsories.

Gymnasts from GDR fully displayed their well-known qualities — precision, safety, amplitude — distancing themselves, with each apparatus, from their opponents.

Sportul, Oct 25, 1970

Gimnaștii din R.D.G. au etalat, din plin, calitățile lor binecunoscute — precizie, siguranță, amplitudine — distanțîndu-se, cu fiecare aparat, de adversarii lor.

All things considered, the East German team met expectations. They showed many difficult elements, but they needed to work on execution.

The GDR team fulfilled expectations in Ljubljana. It was essentially based on Matthias Brehme, Klaus Köste, and Wolfgang Thüne, who distinguished themselves with good performances and made sure that third place was never in danger. Peter Kunze and Bernd Schiller could not play a major role in their debut in such an important competition. […] The optional program of the GDR team contained numerous difficulty elements. The East German gymnasts showed vaults with full twists, and on high bar, Schiller did a double twist, and Kunze a hecht with a full turn. However, the execution is still in need of improvement because valuable tenths were often lost due to unsteadiness.

Neue Zeit, Oct. 28, 1970

Die DDR-Mannschaft erfüllte in Ljubljana die Erwartungen. Sie stützte sich im wesentlichen auf Matthias Brehme, Klaus Köste und Wolfgang Thüne, die sich mit guten Leistungen auszeichneten und dafür sorgten, daß der dritte Platz nie in Gefahr geriet. Peter Kunze und Bernd Schiller konnten bei ihrem Debüt in einem so bedeutenden Wettkampf noch keine große Rolle spielen. […] Das Kürprogramm der DDR-Mannschaft enthielt zahlreiche Schwierigkeiten. So zeigten die DDR-Turner im Pferdsprung Sprünge mit ganzen Drehungen, und am Reck boten Schiller die doppelte Mühle sowie Kunze den Hecht mit ganzer Drehung. Die Ausführung ist allerdings noch verbesserungsbedürftig, denn durch Unsicherheit gingen oft wertvolle Zehntel verloren.

The United States

They had a rough go on pommel horse, rings, and vault.

We led off with Lindner, who worked tight and scared but gave us an 8.50. Next we broke Brent Simmons for a 7.75, and the pressure was on. We couldn’t afford to abort another routine, for now there was no margin for error. The next four men produced, and we were out of the event and home free.

On rings we were shaky, but this was also reflected in our training camp. Few of our gymnasts could pelform the back kip, straightening out the arms before lowering to the back lever. “Mako” was almost flawless in this event and deserved more than the 9.3 awarded. The low score counting on this event was an 8.10 bringing our total down to 42.95 .

Just when we thought things looked bad and couldn’t get any worse, we moved to long horse. Here our score was only 42.45 , and we were forced to use a 7.75. Once again let me point out that these were consistently our poorest events.

Bill Roetzheim, Modern Gymnast, December 1970

Team USA was thrilled to make it to the evening session with the top teams, but they competed nervously as a result.

This high finish garnered us a position in the evening session on Monday night spliced neatly between Russia and Japan. I am not going to deal further with scores or individual placing, for this information is recorded elsewhere for your scrutiny.

The thrill of making it into the evening session was short-lived. The traumatic shock of our young team warming up with the Russians and Japanese was a calamity. It’s hard for a college sophomore not to blow a Diamidov in practice when the guy waiting next in line is Sergei Diamidov. The yelling of the crowd in the next gym coupled with the awe of the other teams in our group had to have a strong psychological effect. That auxiliary gym resembled the Christians’ waiting room prior to entering the coliseum. We didn’t fear the lions, but as luck had it we drew the side horse first and that animal has been known to kick.

Bill Roetzheim, Modern Gymnast, December 1970

The noise made it difficult for Team USA.

Something else that hurt us was the noise generated by the crowd which was following the Japanese and Russians. When you’re competing at the same time as those two heavyweights, not too many people know you’re around. It didn’t matter that we had someone in the middle of a routine. When one of their gymnasts finished, the place went up for grabs.

Bill Roetzheim, Modern Gymnast, December 1970

Men’s hairstyles were on the judges’ minds.

Gene Wettstone, our national coach, said he “learned the secret of winning at these games. It’s a very simple formula — you measure the size of the muscles of the gymnast and subtract the length of the hair to determine potential.” (I wish he had told this to the Swiss before the meet.)

Bill Roetzheim, Modern Gymnast, December 1970

Note: Men’s hair would become a sticking point after the 1971 European Championships. Arthur Gander would threaten a deduction for men with long hair. More here.

West Germany

They were disappointed in their performance.

At the World Championships in Ljubljana, our gymnasts fought so unusually weakly that the professional world shook their heads; because everyone knew the DTB gymnasts to be much stronger. The 1970/71 competition season proved that Ljubljana was an almost puzzling exception.

Jahrbuch der Turnkunst, 1972

Bei den Weltmeisterschaften in Laibach kämpften unsere Kunstturner so ungewöhnlich schwach, daß die Fachwelt den Kopf schüttelte; denn alle kannten die DTB-Turner als sehr viel stärker. Daß Laibach eine fast schon rätselhafte Ausnahme war, hat dann die Wettkampfsaison 1970/71 bewiesen.

Reminder: West Germany hosted the Olympics two years later.

Cuba

The Romanian press was impressed by the Cuban gymnasts’ optional routines:

Regarding the morning competition, it should be noted the high level at which the Cuban gymnasts presented themselves, whose optional exercises were received with keen interest by the specialists, both for their composition and technical value, as well as for their actual execution. A single figure is telling in this regard: the Cubans obtained more than 35 points more in the optional exercises compared to the compulsory exercises.

Sportul, Oct. 27, 1970

In ce privește concursul de dimineață mai este de reținut nivelul ridicat la care s-au prezentat gimnaștii cubanezi, ale căror exerciții liber alese au fost primite cu viu interes de specialiști, atît pentru compoziția și valoarea lor tehnică, cit și pentru execuția propriuzisă. O singură cifră este grăitoare în această privință : la liber alese, cubanezii au obținut cu peste 35 de puncte mai mult decit la impuse!

The All-Around Competition

Reminder #1: There wasn’t a separate individual all-around competition. (Two years later, in Munich, there would be an all-around final for the first time at a World Championships or Olympic Games.) The all-around was contested at the same time that the team competition was contested.

Reminder #2: Kato Sawao, the reigning Olympic champion, tore his Achilles earlier in the year and was unable to compete. You can read about it here.

The Top 15

| Gymnast | Ctry | FX | PH | SR | VT | PB | HB | Total |

| 1. Kenmotsu Eizo | JPN | 115.05 | ||||||

| C. | 9.55 | 9.50 | 9.35 | 9.40 | 9.65 | 9.55 | 57.00 | |

| O. | 9.60 | 9.75 | 9.55 | 9.60 | 9.75 | 9.80 | 58.05 | |

| 2. Tsukahara Mitsuo | JPN | 113.85 | ||||||

| C. | 9.45 | 9.25 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 9.40 | 9.45 | 56.65 | |

| O. | 9.35 | 9.10 | 9.70 | 9.75 | 9.50 | 9.80 | 57.20 | |

| 3. Nakayama Akinori | JPN | 113.80 | ||||||

| C. | 9.40 | 8.30 | 9.60 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 9.65 | 56.05 | |

| O. | 9.55 | 9.50 | 9.80 | 9.40 | 9.80 | 9.70 | 57.75 | |

| 4. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 113.75 | ||||||

| C. | 9.35 | 8.75 | 9.55 | 9.35 | 9.75 | 9.65 | 56.40 | |

| O. | 9.25 | 9.60 | 9.70 | 9.35 | 9.75 | 9.70 | 57.35 | |

| 5. Klimenko, Viktor | URS | 113.60 | ||||||

| C. | 9.45 | 9.40 | 8.45 | 9.40 | 9.65 | 9.55 | 55.90 | |

| O. | 9.55 | 9.70 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 9.70 | 9.65 | 57.70 | |

| 6. Honma Fumio | JPN | 113.45 | ||||||

| C. | 9.30 | 9.40 | 9.25 | 9.45 | 9.55 | 9.70 | 56.65 | |

| O. | 9.30 | 9.45 | 9.50 | 9.30 | 9.65 | 9.60 | 56.80 | |

| 7. Hayata Takuji | JPN | 112.90 | ||||||

| C. | 9.05 | 9.25 | 9.30 | 9.35 | 9.60 | 9.65 | 56.20 | |

| O. | 9.30 | 9.30 | 9.60 | 9.35 | 9.50 | 9.65 | 56.70 | |

| 8. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 112.85 | ||||||

| C. | 9.55 | 9.00 | 9.20 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 9.25 | 56.10 | |

| O. | 9.45 | 9.15 | 9.60 | 9.30 | 9.70 | 9.55 | 56.75 | |

| 9. Cerar, Miroslav | YUG | 112.50 | ||||||

| C. | 9.20 | 9.70 | 8.95 | 8.95 | 9.60 | 9.50 | 55.90 | |

| O. | 9.40 | 9.75 | 9.10 | 9.10 | 9.55 | 9.70 | 56.60 | |

| 10. Diomidov, Sergei | URS | 112.45 | ||||||

| C. | 9.20 | 9.35 | 9.10 | 9.20 | 9.60 | 9.30 | 55.75 | |

| O. | 9.50 | 9.55 | 9.30 | 9.30 | 9.65 | 9.40 | 56.70 | |

| 11. Brehme, Mathias | GDR | 112.10 | ||||||

| C. | 9.25 | 9.40 | 9.10 | 9.20 | 9.35 | 9.50 | 55.80 | |

| O. | 9.15 | 9.55 | 9.40 | 9.25 | 9.35 | 9.60 | 56.30 | |

| 12T. Sakamoto, Makoto | USA | 111.65 | ||||||

| C. | 9.30 | 9.15 | 9.30 | 9.05 | 9.50 | 9.40 | 55.70 | |

| O. | 9.20 | 9.25 | 9.40 | 9.20 | 9.30 | 9.60 | 55.95 | |

| 12T. Lisitsky, Viktor | URS | 111.65 | ||||||

| C. | 8.95 | 9.15 | 9.35 | 9.20 | 9.45 | 9.10 | 55.20 | |

| O. | 9.40 | 9.35 | 9.50 | 9.25 | 9.45 | 9.50 | 56.45 | |

| 14. Köste, Klaus | GDR | 111.40 | ||||||

| C. | 9.25 | 9.05 | 8.85 | 9.20 | 9.45 | 9.60 | 55.40 | |

| O. | 9.25 | 9.10 | 9.20 | 9.35 | 9.40 | 9.70 | 56.00 | |

| 15. Kubica, Mikołaj | POL | 111.25 | ||||||

| C. | 8.85 | 9.40 | 9.35 | 8.90 | 9.30 | 9.35 | 55.15 | |

| O. | 9.15 | 9.45 | 9.40 | 9.10 | 9.50 | 9.50 | 56.10 |

Voronin messed up his compulsory pommel horse routine, taking him out of medal contention.

Only the Soviet Mikhail Voronin, 1966 world champion and silver medalist in Mexico City, managed to insert himself [between the Japanese gymnasts]. He could have done better than fourth if he hadn’t missed his exercise on pommel horse, which only earned him 8.75 points.

L’Impartial, Oct. 26, 1970

Seul le Soviétique Mikhail Voronine, champion du monde 1966 et médaille d’argent à Mexico, a réussi à s’intercaler. Il aurait d’ailleurs pu faire mieux que quatrième s’il n’avait raté son exercice au cheval-arçons, exercice qui ne lui a rapporté que 8,75 points.

Nakayama Akinori also messed up his compulsory pommel horse.

The general interest was focused on the Japanese Nakayama Akinori. After his bad luck in the individual all-around — an error on the compulsory pommel horse, which earned him an [8.30] — he was first three times (floor exercise, rings and parallel bars) and second once (horizontal bar).

L’Impartial, Oct. 28, 1970

L’intérêt général se concentra sur le Japonais Akinori Nakayama. Après sa malchance au combiné individuel — faute au cheval d’arçons imposé qui lui valut un [8,30] — il fut trois fois premier (exercices au sol, anneaux et barres parallèles) et une fois second (barre fixe).

Kenmotsu didn’t expect to win the all-around title.

“Honestly, I did not expect that I would succeed in seizing a world championship again. I owe the title in large part to the great camaraderie on the squad. When my chances after the compulsory parts were favorable, everyone had to rally behind me as one man. That gave me so much self-confidence that it worked.”

De Tijd, Oct. 27, 1970

„Eerlijk gezegd had ik niet verwacht dat ik er nog eens in zou slagen op een wereldkampioenschap beslag te leggen. Ik heb de titel voor een belangrijk deel te danken aan de enorme kameraadschap in de ploeg. Toen mijn kansen na de verplichte onderdelen gunstig lagen hoeft iedereen zich als één man achter mij geschaard. Daardoor kreeg ik zo veel zelfvertrouwen dat het lukte.”

East Germany showed improvement in the all-around even though they had a long way to go to catch the Soviet and Japanese gymnasts in the team competition.

But there is at least small progress in the individual classification. In Mexico, Brehme was 12th, here 11th, Köste 16th, here 14th, Dietrich 34th, here 21st, newcomer Thüne was 16th, Kunze 29th, Schiller 31st. The gap between the team and the winner in Mexico was 18.85 points, here the difference is 17.95 points.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 28, 1970

Doch deuten sich wenigstens kleine Fortschritte im Einzelklassement an. In Mexiko war Brehme 12., hier 11. , Koste 16., hier 14., Dietrich 34., hier 21., Neuling Thüne konnte 16., Kunze 29., Schiller 31. werden. Der Abstand der Mannschaft zum Sieger hatte in Mexiko 18,85 Punkte betragen, hier beträgt die Differenz 17,95 Punkte.

The Dutch were pleased with their performances.

Anyone who would have predicted to Dutch insiders in the gymnastics world before the world championships that our gymnasts would do better than the women’s team would certainly have been looked at with a bit of pity about so much incompetence. But the miracle did happen: because the three individual participants, Cor Smulders, Hans Gunneman, both from PSV, and the Volendammer Peter Karregat all did reasonably well.

Limburgsch dagblad, Oct. 27, 1970

Wie voor de wereldkampioenschappen aan Nederlandse ingewijden in de turnwereld zou hebben voorspeld dat onze turners het beter zouden doen dan de damesploeg, zou stellig een beetje meewarig zijn aangekeken over zoveel ondeskundigheid. Maar het wonder is dan toch gebeurd: want de drie individuele deelnemers, Cor Smulders, Hans Gunneman, beiden van PSV, en de Volendammer Peter Karregat hebben het er alle drie redelijk goed afgebracht.

Note: Smulders finished 96th, Karregat was 123rd, and Gunneman was 127th.

Event Finals

Reminder: Only six gymnasts qualified for event finals. Qualification for finals was based on the compulsory *and* optional scores on each event.

A gymnast’s final score was the average of his compulsory and optional scores + the score for his routine during event finals.

COA = Compulsory + Optional Average

Floor Exercise

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.475 | 9.550 | 19.025 |

| 2. Kenmotsu | JPN | 9.575 | 9.400 | 18.975 |

| 3. Kato | JPN | 9.500 | 9.400 | 18.900 |

| 4. Hristov | BUL | 9.475 | 9.400 | 18.875 |

| 5. Tsukahara | JPN | 9.400 | 9.400 | 18.800 |

| 6. Klimenko | URS | 9.500 | 9.150 | 18.650 |

There were a lot of errors during the floor final.

The floor exercise, the extremely spectacular game, in which the gymnast is completely dependent on his own body, was curiously the lowest scoring of the six finals. Apparently nerves played a major role in this opening part. Mistakes were made, and only Nakayama, who had went first, came above 9.50.

Tubantia, Oct. 28, 1970

De vrije oefening, het uiterst spectaculaire spel, waarin de turner geheel op zijn eigen lichaam is aangewezen, was van de zes finales merkwaardig genoeg de minste. Op dit openingsonderdeel speelden kennelijk de zenuwen een grote rol. Er werden fouten gemaakt en alleen Nakayama, die als eerste gestart was, kwam boven de 9.50.

Hristov, the 1969 European Floor Champion, had an error on his double back.

The European champion, Hristov (Bulgaria), also made a nice impression, even if his double back was not completely successful. Unfortunately, the penalty applied by the judges took him off the podium.

Sportul, Oct. 29, 1970

O frumoasă impresie a produs și campionul Europei, Hristov (Bulgaria), chiar dacă dublul său salt n-a fost integral reușit. Din păcate, penalizarea aplicată de arbitri i-a scos in afara podiumului.

Pommel Horse

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Cerar | YUG | 9.725 | 9.650 | 19.375 |

| 2. Kenmotsu | JPN | 9.625 | 9.700 | 19.325 |

| 3. Klimenko | URS | 9.550 | 9.500 | 19.050 |

| 4. Vratič | YUG | 9.550 | 9.450 | 19.000 |

| 5. Brehme | GDR | 9.475 | 9.400 | 18.875 |

| 6. Kubica, W. | POL | 9.550 | 8.950 | 18.500 |

Rings

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.700 | 9.700 | 19.400 |

| 2. Tsukahara | JPN | 9.600 | 9.650 | 19.250 |

| 3. Voronin | URS | 9.625 | 9.600 | 19.225 |

| 4T. Kenmotsu | JPN | 9.450 | 9.450 | 18.900 |

| 4T. Hayata | JPN | 9.450 | 9.450 | 18.900 |

| 6. Lisitsky | URS | 9.425 | 9.250 | 18.675 |

Nakayama — indisputably the best ring man and even of the World Championships — won his second world champion title on this event.

Sportul, Oct. 29, 1970

Nakayama — indiscutabil cel mai bun om al inelelor și chiar al C.M. — a ciștigat al doilea său titlu de campion al lumii la această probă.

Vault:

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Tsukahara | JPN | 9.675 | 9.450 | 19.125 |

| 2. Klimenko | URS | 9.500 | 9.500 | 19.000 |

| 3. Kato | JPN | 9.400 | 9.200 | 18.600 |

| 4. Honma | JPN | 9.375 | 8.950 | 18.325 |

| 5. Kenmotsu | JPN | 9.500 | 8.625 | 18.125 |

| 6. Nakayama | JPN | 9.450 | 8.575 | 18.025 |

During the optionals portion of the team/all-around competition, the audience protested Tsukahara’s score.

Here’s a Russian account:

It just so happens that at every big gymnastic competition, the judges, at least once, come into open conflict with the audience. This time, a violent disagreement arose over the original vault of the Japanese Tsukahara. The judges scored him quite high — 9.75. But the tribunes protested. The noise and din filled the Tivoli for several minutes. But, naturally, to no avail: the judges, of course, remained adamant.

Nedelia, Oct. 26, 1970

Так уж случается, что на каждом большом гимнастическом соревновании судьи хоть раз, да вступят в открытый конфликт с трибуной. На этот раз бурное несогласие возникло из-за оригинального прыжка японца Цукахары. Судьи оценили его достаточно высоко — 9,75. Но трибуны запротестовали. Шум и гам не сколько минут наполняли «Тиволи». Но, естественно, безрезультатно: судьи остались, конечно, непреклон ными.

What did Tsukahara think about his scores during the qualification round?

But was the public actually right in such a reaction? Tsukahara: “I think the first vault was perfect. But I didn’t get very high on the second. I think there was nothing to criticize about that 9.75.” Endo added: “He’s absolutely right. But that’s why it was nice that the audience sympathized with him so much.”

De tijd, Oct. 27, 1970

Maar had het publiek eigenlijk wel gelijk met een dergelijke reactie? Tsukahara: „De eerste sprong was naar mijn gevoel perfect. Maar bij de tweede kwam ik niet hoog Volgens mij was er op die 9.75 niets aan te merken.” Vulde Endo aan: „Hij heeft volkomen gelijk. Maar daarom was het toch wel leuk, dat het publiek zo met hem meeleefde,”

During finals, Tsukahara performed a Tsukahara after performing an “orthodox” vault.

However, [Klimenko] couldn’t threaten Tsukahara Mitsuo, who had introduced his new almost implausible vault the day before. Nevertheless, the Japanese did not take any risk on his first attempt. He first performed an orthodox vault flawlessly, to ensure a high score. Immediately afterwards followed the “Tsukahara,” as this vault will undoubtedly go down in history. The score of 9.60 points, five hundredths less than Klimenko got, was enough for recognition as the best vaulter in the world.

Tubantia, Oct. 28, 1970

Hij kon echter Mitsuo Tsukahara, die daags tevoren zijn nieuwe bijna ongeloofwaardige sprong had geïntroduceerd, niet bedreigen. Toch ram de Japanner bij zijn eerste poging geen enkel risico. Hij voerde eerst een orthodoxe sprong feilloos uit, om zeker te zijn van een hoge waardering. Direkt daarna volgde dan de „Tsukahara”, zoals deze sprong ongetwijfeld de geschiedenis in zal gaan. De waardering van 9,60 punten, vijfhonderdste minder dan Klimenko kreeg, was voldoende voor erkenning als de beste paardspringer ter wereld.

Reportedly, Tsukahara was going to call the vault the “Tivoli Vault” (named after the arena in Ljubljana).

The vaults were awaited with great interest, especially for what Tsukahara was going to achieve. In the competition, he completely confirmed the predictions, presenting again his original vault (seen in the world premiere in Bucharest) which — to the satisfaction of the audience, which received him with great sympathy — he agreed to call it the “Tivoli vault.”

Sportul, Oct. 29, 1970

Săriturile au fost aşteptate cu mult interes, mai ales pentru ceea ce urma să realizeze Tsukahara. In concurs el a confirmat întrutotul pronosticurile, prezentând din nou originala sa săritură (văzută în premieră mondială la Bucureşti) pe care — dind satisfacţie publicului, care l-a primit cu multă simpatie — a acceptat să o denumească “săritura Tivoli.”

Note: In early October of 1970, the Japanese and Romanian gymnasts performed together. Hence the reference to Bucharest in the quote above.

Parallel Bars

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.700 | 9.700 | 19.400 |

| 2T. Kenmotsu | JPN | 9.700 | 9.550 | 19.250 |

| 2T. Voronin | URS | 9.750 | 9.500 | 19.250 |

| 4. Kato | JPN | 9.650 | 9.550 | 19.200 |

| 5. Klimenko | URS | 9.675 | 9.500 | 19.175 |

| 6. Diomidov | URS | 9.625 | 9.300 | 18.925 |

High Bar

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Kenmotsu | JPN | 9.675 | 9.800 | 19.475 |

| 2. Nakayama | JPN | 9.675 | 9.700 | 19.375 |

| 3T. Hayata | JPN | 9.650 | 9.700 | 19.350 |

| 3T. Köste | GDR | 9.650 | 9.700 | 19.350 |

| 5. Voronin | URS | 9.675 | 9.600 | 19.275 |

| 6. Honma | JPN | 9.650 | 9.600 | 19.250 |

Voronin reportedly was not happy about the high bar results.

Mikhail Voronin pushed angrily made his way through a crowd in the hallway to the locker room, rightly so, because what he had shown on horizontal bar, culminating in a tremendous twisting dismount should have been worth more than 9.60 points.

With that, the last Russian chance to win at least a bronze medal at the end of this tournament disappeared. Voronin said bitterly: “I didn’t deserve that.”

NRC Handelsblad, Oct. 28, 1970

Terwijl hij deze uitspraak deed, baande Mihael Voronin zich boos een weg door een menigte in de gang naar de kleedkamer. Terecht, want wat hij aan de rekstok had laten zien, met als hoogtepunt een geweldige schroefsprong naar de grond, had méér dan 9.60 pnt. moeten opleveren.

Daarmee verdween de laatste Russische kans, om aan het eind van dit toernooi tenminste nog een bronzen medaille te veroveren. Zei Voronin afgebeten: „Dat had ik niet verdiend'”.

It was a late night.

One hour before midnight on Tuesday evening in the Tivoli Hall in Ljubljana, the 1970 gymnastics championships came to an end with the men’s horizontal bar. The third gymnast was our Klaus Köste. Before Köste, the Japanese Hayata had received 9.70 points for his lively exercise. Then Hayata’s teammate Honma took the apparatus.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 29, 1970

Eine Stunde vor Mitternacht gingen am Dienstagabend in der Tivoli-Halle von Liubliana die Turnweltmeisterschalten 1970 mit dem Reckflnale der Männer zu Ende. Als dritter Turner ging unser Klaus Köste ans Gerät. Vor Koste hatte der Japaner Hayata für seine schwungvolle Übung 9,70 Punkte erhalten. Dann war Hayatas Mannschaftskamerad Honma ans Gerät gegangen.

The late night was blamed, partially, on elderly people.

So everyone has swarmed to all corners of the world again. Satisfied or not. Everyone can agree on one thing: the Yugoslavs have ensured a perfect organization in all those days. The program was executed accurately to the minute. Only last night the schedule got a bit messed up. But that was largely due to the many ceremonial medals awarded by elderly ladies and gentlemen, with all the inevitable spectacle surrounding it.

De tijd, Oct. 28, 1970

Zo is iedereen weer naar alle uithoeken van de wereld uitgezwermd Tevreden of niet. Maai over één ding kan iedereen het eens zijn: do Joegoslaven hebben in al die dagen voor een perfecte organisatie gezorgd. Het programma werd tot op de minuut nauwkeurig afgewerkt. Alleen gisteravond liep het schema wat in de war. Maar dat moest voor het grootste deel worden toegeschreven aan de vele malen dat er plechtige medailles door bejaarde dames en heren werden uitgereikt, met alle onvermijdelijke show daar omheen.

But no one regretted staying until the end.

Late on Tuesday evening, when Nakayama began his floor exercise in the apparatus final of the [World Championships], Tivoli Hall was full again. Locals, groups of tourists from other cities of Yugoslavia, gymnasts participating in the competition showed up for the last meeting with the best of the best participants. After more than three hours of competition, when, on high bar, Voronin executed the last giant and then the grandmaster landing, it was long past midnight. However, none of those who watched the finalists’ competitions felt the passage of time, none regretted the presence at this last act of the W.C. in 1970.

Sportul, Oct. 29, 1970

Marți seara tirziu, când Nakayama și-a început exercițiul la sol din cadrul finalei pe aparate a C.M., sala Tivoli era din nou arhiplină. Localnici, grupuri de turiști din alte orașe ale Iugoslaviei, gimnaști participanți la competiție se prezentau la ultima lor întîlnire cu cei mai buni dintre cei mai buni participanți. După mai bine de trei ore de concurs, în momentul când, la bară, Voronin executa ultima gigantică și apoi aterizarea de mare maestru, trecuse de mult de miezul nopții. Nimeni, insă, din cei care au urmărit întrecerile finaliștilor nu a simțit trecerea timpului, nimeni nu a regretat prezența la acest ultim act al C.M. 1970.

Additional Quotes

Endo Yukio, the head coach of the Japanese men’s team, on Kenmotsu:

“I can’t say that Kenomtsu’s win came as a surprise to us, we knew it was possible. What sets Kenmotsu apart from others? I do not know very well. He has less physical power than Tuskahara, for example, he is less attractive to the eye than Nakayama. If you will, he doesn’t have a particular quality that he can really make his own. He was for a long time ranked among the best gymnasts in our country, but some believed that he would not step out of the ranks. For Mexico (where he finished 4th), his selection was imposed by the numbers, but we did not really expect to see him take third place on our team. It was there that we realized that he was a sure man, not very emotional, always true to form. I think it also revealed him a bit to himself. He considered himself until then as a good product of our school, without having much ambition. He was good everywhere, but the best nowhere. For two years he has worked a lot, not trying to improve technically, because he knew how to do everything, but first seeking to personalize his work. His Mexico City moves were completely changed as a result. He chose them, in three months, and then he worked on them, when he was far from mastering certain difficulties. The triple twist on floor, which he missed in the final, cost him hours and hours of work. He knew he was taking a big risk, and a risk that wouldn’t necessarily pay off.

Boys like Kenmotsu, we have others in Japan, and a few young people who, from here to Munich, may even be brighter.

On a human level, Kenmotsu is a charming companion. He speaks little, but he poses no problems.”

L’Équipe, October 30, 1970

«Je ne peux pas dire que la victoire de Kenomtsu soit pour nous une surprise, nous savions qu’elle était possible. Ce qui distingue Kenmotsu des autres? Je ne sais pas très bien. Il a moins de puissance physique que Tuskahara par exemple, il est moins joli à l’oeil que Nakayama. Si vous voulez, il n’a pas une qualité particulière qui puisse vraiment le personnaliser. Il a été longtemps, chez nous, classé parmi les meilleurs gymnastes, mais certains croyaient qu’il ne sortirait pas du rang. Pour Mexico (où il finit 4e), sa sélection s’était imposée par les chiffres, mais on ne s’attendait pas tellement à le voir prendre la troisième place au sein de notre équipe. C’est là qu’on s’aperçut qu’il était un homme sûr, peu émotif, toujours égal à lui-même. Je crois que cela l’a aussi un peu révélé à lui-même. Il se considérait justqu’alors comme un bon produit de notre école, sans avoir beaucoup d’ambition. Il était bon partout, mais le meilleur nulle part. Depuis deux ans il a beaucoup travaillé, cherchant non pas à s’améliorer sur le plan technique, car il savait tout faire, mais cherchant d’abord à personnaliser son travail. Ses mouvements de Mexico ont ainsi été complètement modifiés. Il les a choisis, en trois mois, et ensuite il les a travaillés, alors qu’il était loin de maîtriser certaines difficultés. La triple vrille au sol, qu’il a ratée en finale lui a coûté des heures et des heures de travail. Il savait qu’il prenait un gros risque, et un risque qui ne paierait pas forcément.

Des garçons comme Kenmotsu, nous en avons d’autres au Japon, et quelques jeunes qui, d’ici à Munich, seront même peut-être plus brillants.

Sur le plan humain, Kenmotsu est un charmant compagnon. Il parle peu, mais il ne pose pas de problèmes.»

Cerar ended his gymnastics career in his home country.

“Although I started to doubt myself after this triumph, the public can assume that I will stop. I am now 31 and have had a wonderful sports career. I have been in gymnastics since I was 16 years old, have participated in a world championship twelve times, and, in that time, have won about thirty medals, three of which were gold at a world championship: once on parallel bars and twice on pommel horse.”

“Tonight my compatriot Miloš Vratič participated on pommel horse [in the finals]. That’s a sign that he has aptitude. I hope to be able to teach him a lot. Furthermore, it is my intention to become involved in the education of promising youth. How or in what function I don’t know yet. It depends on my busy work, how much time I can spend on it.”

NRC Handelsblad, October 28, 1970

„Hoewel ik na deze triomf een beetje aan mij zelf ben gaan twijfelen, mag het publiek toch wel aannemen dat ik er mee ophoud. Ik ben nu 31 en heb een schitterende sportcarrière achter de rug. Ik turn al vanaf mijn 16de jaar, heb twaalf maal aan een wereldkampioenschap meegedaan en in die tijd zo ongeveer dertig medailles behaald, waarvan drie gouden op een wereldkampioenschap: eenmaal aan de brug en twee keer met paardvoltigeren.”

„Vanavond deed mijn landgenoot Milko Vratic mee met het paardvoltigeren. Dat is een teken dat hij aanleg bezit. Ik hoop hem veel te kunnen leren. Verder is het mijn bedoeling, me met de opleiding van veelbelovende jeugd bezig te gaan houden. Hoe of in welke functie weet ik nog niet. Het hangt van mijn drukke werkzaamheden af, hoeveel tijd ik daaraan kan besteden.”

Note: Cerar was a lawyer at that time. Hence the reference to his work schedule.

Note #2: Cerar’s gold on parallel bars was controversial, inciting discussions of abandoning the 10.0 system in 1962.

Cerar got many an ovation.

a day in which dozens of times, Tivoli Hall rewarded each appearance of the legendary Miroslav Cerar with long and repeated applause as he fought titanically, probably for the last time […]

Sportul, Oct. 25, 1970

zi în care de zeci de ori, sala Tivoli a răsplătit cu îndelungi și repetate aplauze fiecare apariție a legendarului Miroslav Cerar luptînd titanic, probabil pentru ultima oară […]

George Kunzle, a judge from England, found a lot of the routines to be monotonous. The exceptions were the pommel horse final, the Swiss men, and the Cubans on floor and vault.

Sitting back and viewing the competition as a whole, my overriding impression was one of monotony, not in detail but in general. All the winning exercises on each piece of apparatus had a sameness of style and execution, even of perfection, which became tedious after a while. This impression of the finals was underlined by one notable exception of the Pommel Horse where we did see the contrasts of Cerar’s smooth, stately progression, Kato’s domination of incredibly complex and intricate movements, Kubica’s verve and swing and Brehme’s crips efficiency. Having five different nationalities in that final probably made all the difference. Elsewhere it was Japan, Japan and more Japan. I do not wish to detract from the incredible work these diminutive men produced — it was superb in style, execution and breathtaking in difficulty. But they all do much the same kind of work and with so many in most of the finals, the work had a sameness about it which depressed me. Watching the voluntary exercises I found the only real excitement in some exercises of the middle range of gymnasts such as the Swiss on the parallels and horizontal bar where they seemed to show an originality of composition quite foreign to the top performers. The best moments of the entire competition for me were watching the Cubans tumble and vault — what verve and spring, throwing their somersaults two to three feet higher than anyone else and doing a Yamashita vault which at least showed me why the best Japanese should still lose two to three tenths for flight! What matter they stumbled a little on landing — they were superb in that they expressed their own personality in their work in contrast to the well-trained, superbly competent, technicians who proved unbeatable in their objectives of obtaining maximum marks.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1970

George Kunzle also worried that the Code of Points was too technical and prescriptive.

Watching over 130 versions of the identical floor exercise, dissecting each in minute and critical detail and applying a set of complex rules and regulations to the corpse to arrive at a final mark must have made me hungry for a more emotional response to the beauty and expression of gymnastics. I think that as judges we must occasionally ask ourselves whether we want a true work of art presented to us, a performance which moves us and makes us exclaim involuntarily for joy at watching it , or whether we want perfection of technological execution and difficulty. Maybe, in our relentless pursuit of standardization, codification, detailed breakdown, and exposition as .personified in our Code of Points, we will breed a race of judges so technically competent that they will be totally unable to recognize an exercise of true genius when executed before them. I felt that I and my colleagues were technicians without parallel who applied our Code of Points with cold calculating precision.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1970

Because of all the “relentless logic,” Kunzle missed the days of cheating.

I am sure that, with the same relentless logic, we placed the teams and individuals in their correct serried rankings, depersonified into statistics on the local Ljubljana city computer. In such an atmosphere, I must confess to occasional heretical yearnings for a bit of good old-fashioned political or national cheating — it would have been so much more fun; and whatever else Ljubljana may have been, it wasn’t fun!

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1970

Tsukawaki Shinsaku: What does he think will change before the next World Championships in 1974?

Much has changed, and a lot will change. For example, not long ago, at a time when Tsurumi, Yamashita, and Endo, who is now taking our team to the competition, were creating the glory of Japanese gymnastics, everything was different. These athletes began to train seriously at the age of 14-15, and a lot of their time wasted in vain. Now we are starting to study gymnastics in elementary school — from the age of 6 and, after graduating from elementary school, they already possess real skill. You have to work very hard for this, and in the future, of course, you cannot expect it to be easier! Because in modern gymnastics at large competitions, an athlete must completely exclude the possibility of mistakes.

I saw Soviet gymnasts in Moscow, Rome, and Melbourne — they worked without mistakes. And I saw them in Tokyo, Mexico City and now in Ljubljana — there was, it seems, not a single one who, at least once, did not make a mistake. In our team, only one Nakayama made a mistake on the first day of the competition, performing on horse. A few years ago we adopted your [i.e. Soviet] training methodology and since then we have not been mistaken. What’s going on? And in four years, the requirements will be even stricter, and we have to prepare for this now.

Nedelia, Oct. 26, 1970

Многое изменилось и многое изменится. Например, еще недавно, во времена, когда Цуруми, Ямасита и Эндо, который теперь выводит нашу команду на соревнования, создавали славу японской гимнастики, все было по-другому. Эти спортсмены начали всерьез тренироваться лет в 14—15, и много времени у них пропало напрасно. Теперь у нас начинают изучать гимнастику в младшем классе школы — с 6 лет и, закончив ее, уже владеют настоящим мастерством. Работать для этого приходится очень много, и в дальнейшем, конечно, нельзя ожидать, что будет легче! Потому что в современной гимнастике на больших соревнованиях спортсмену надо совсем исключить возможность ошибок.

Я видел советских гимнастов в Москве, Риме, Мельбурне — они работали без ошибок. И я видел их в Токио, Мехико и сейчас в Любляне — не было, кажется, ни одного, кто бы хоть раз, да не ошибся. У нас в команде ошибся только один Накаяма в первый день соревнований, выступая на коне. Несколько лет назад мы приняли вашу методику тренировок и с тех пор не ошибаемся. Что же происходит? А через четыре года требования будут еще строже, и к этому приходится готовиться уже сейчас.

The same question for Karl-Heinz Zschocke, head coach of the GDR Men’s Team and member of the Men’s Technical Committee

I am sure that gymnastics will develop in the direction of even greater difficulty and at a much faster pace than now. In Ljubljana, we saw how the general level of gymnastic culture rose, and the level of difficulty among the strongest, for example, Voronin, also became even higher. But in order to master this difficulty and be able to demonstrate it in competitions, one must also have psychological stability. This will have to be taken care of more in the future than we are doing now.

Nedelia, Oct. 26, 1970

Я уверен, что гимнастика будет развиваться в направлении еще большей трудности и гораздо более бурными темпами, чем сейчас. В Любляне мы видели, как поднялся общий уровень гимнастической культуры, а уровень трудности у сильнейших, например у Воронина, тоже стал еще выше. Но, чтобы этой трудностью овладеть и суметь ее продемонстрировать на соревнованиях, нужно обладать также психологической стабильностью. Об этом придется в дальнейшем заботиться больше, чем мы это делаем сейчас.

Vladimir Smolevsky, the head coach of the USSR men’s national team: If he could give out an additional prize, what would it be?

Prize for Courage. I would give it to Mikhail Voronin. No one — neither the judges, let alone the audience — noticed that this man had been performing every day, suffering from severe pain in his shoulder, which he had injured back in August at the competitions for the national cup. And how he stood in front of the rings, waiting for a minute or two for the noise, whistles, and loud stomping, which happened by mistake, to cease! He stood alone in front of the apparatus — and waited. And he did not flinch. These minutes are expensive.

Nedelia, Oct. 26, 1970

Приз за мужество. Я дал бы его Михаилу Воронину. Никто — ни судьи, ни тем более зрители не заметили, что этот человек все дни выступал, страдая от сильной боли в плече, которое повредил еще в августе на соревнованиях за кубок страны. А как он стоял перед кольцами, минуту-другую ожидая, чтобы смолкли шум, свист и громкий марш, который включили по ошибке! Он стоял один перед снарядом — и ждал. И не дрогнул. Эти минуты дорого стоят.

Note: Voronin’s shoulder had long been an issue. For example, at the 1967 Olympic Test Event, Voronin injured his shoulder during warm-ups.

Note #2: Gymnastics meets seem to be more raucous back in the day.