Like many top gymnasts, Mikhail Voronin did not set out to become a gymnast. He liked soccer and hockey much more. When he was 13, one gymnastics coach looked at his body type and turned him away. But he caught the eye of his physical education teacher, Konstantin Sadikov, and that’s how his journey got started.

As you’ll see below, coaches are often the central characters in Voronin’s 1976 autobiography, Number One (Первый номер), which is understandable. After all, his coaches helped guide him to success, and there was a certain mystique around champion coaches in the international gymnastics community at the time.

At the same time, Voronin is building a larger argument: his career was often mismanaged, and the coaches surrounding him did not always guide him or his teammates in the right way. (This point will be further emphasized in the chapter on the Mexico City Olympics, which will be the subject of the next post.)

Note: Chapters of Voronin’s book were translated into Estonian for the newspaper Spordileht, and I have translated the chapter from Estonian into English. The following excerpts come from the January 11, 1978, January 13, 1978, and January 16, 1978 issues of Spordileht.

“DYNAMO” STADIUM, MY SECOND HOME

We were living near the “Dynamo” stadium. I lost my father when I was quite small, and it was difficult for my mother to raise me. The salary was small because she worked as a cleaner. We didn’t go hungry, but we were poorly dressed.

I enjoyed school, my studies went smoothly, but going to the “Dynamo” stadium was much more exciting to me; there, we used to play soccer for hours. In the winter, however, it was where I put on my skates and skated my heart out.

“Dynamo” stadium is a whole separate world. To us boys, it became like a second home. We saw well-known athletes and admired them wide-eyed. Athletes were a special kind of people, funny, likeable guys; they were fashionably dressed, some of them had a car. But during the training, their shirts were so wet that they wrung out the water; we could see their hair matted together, their breathing interrupted, their eyes tired… They were training. Yes, they were training, and we were surprised that it could be this difficult.

I didn’t like gymnastics very much; there was no game, it was not addictive to me. But the musculature of the gymnasts was great, and I thought that these boys were very strong.

I was 13 years old when I made my first timid attempt to enter the gymnastics section. The coach looked at my skinny figure, long, thin neck, and said no. It didn’t really sadden me, but I still went to the gym to see what gymnastics was all about.

I think that was the first time I saw Shakhlin. Whether it was at the cinema or during training at “Dynamo,” I don’t remember exactly. My desire to start gymnastics had grown stronger by then, and I made another attempt.

Our physical education teacher Konstantin Sadikov had previously been a gymnast and was now managing the section. I caught his eye at the school skating competition. I was already playing hockey at “Dynamo” and was making some progress. Sadikov included me in the training group.

It is difficult to remember my first steps in sports. For example, I don’t remember what kind of exercises we started with at school. The gymnastic equipment was fascinating; it was interesting because success came only with great effort.

FIRST COACHES

We moved to Shchukino. It was far away, but I didn’t leave my Moscow school. I didn’t want to go home after class, so I went to “Dynamo” again. I messed around on the parallel bars, rings, pommel horse; I tried to come up with something more interesting. Then the main training started. Sometimes I was terribly tired, but I couldn’t show it, and I tried not to fall behind the other boys. These extra practices brought great benefits: I became stronger, I learned new elements faster than others.

After a year, we were transferred to Vitaly Belyaev’s group. Belyaev was an interesting person. In his youth, his interests were music, foreign languages, and sports. He began studies at the Institute of International Relations but did not graduate because of the war.

Then he became a coach. Fanatically in love with his job, he didn’t really have a home or a family. There was only gymnastics. However, he was not a cold-blooded fanatic with a one-track mind, the goal to produce a leading gymnast by any means necessary. No, Belyaev was a different kind of fanatic. He was an inquisitive man with great knowledge. He was so focused on his coaching work that his creative joy and search completely took over his private life.

When we started training with his group, he was already over 40 years old, and twenty champion athletes had been trained under him. He chose us himself, he had a nose for talent. And now a completely different kind of gymnastics began…

For five years, Belyaev was everything to us. We believed in him, listened to him; our successes were his successes, and it seemed that fortune finally smiled on him. Our group was as follows: silver medalist of the USSR Youth Cup Leonard Ryzhkov, All-Union Youth Champion Volodya Kokorev, member of the USSR national team Vyacheslav Davydov, Volodya Sosin, who participated in many international tournaments and was a reserve member for Mexico Olympic Games, master athletes and first gymnasts of Moscow Misha Privess, Vitaly Lomtev, and Yura Filippov. We all studied together with Belyaev.

“Soon only Belyaev boys will be on the team,” the other coaches envied.

But it turned out differently. Our group began to fall apart. And it was by the fault of… Vitaly Belyaev.

We were steadily moving up the ranks of mastery, and there were no rivals among our peers. In Moscow and “Dynamo” championships and other tournaments everywhere, Belyaev’s students won because they did gymnastics differently than others. Some performed worse, some better, but everyone demonstrated high class and very difficult routines for that time.

Belyaev knew how to work with children, and he loved it. He was not only a coach but an educator in the best sense of the word. He took care of us like a mother. I’m not saying he didn’t teach us independence, not at all. However, over time, Belyaev’s love became blind.

We were growing up, some were already 20 years old; I was nineteen. But Belyaev, apparently blinded by our progress, did not realize that we were already grown up; we had become men. I saw how, over time, dissatisfaction grew among the boys; they resented the harsh rules set for minors.

In 1965, when I came second in the championship of the USSR, our group began to fall apart. First, Kokorev and Ryzhkov left after the conflict. We were already surrounded by all kinds of patrons, sly coaches who offered the boys all kinds of benefits and advised them to leave the “stupid fanatic” Belyaev.

Then the group broke up for good. Belyaev left “Dynamo,” and we were left by ourselves…

SIDE BY SIDE

What happened next?

I was planning to go to Konstantin Karakashyants, but I did not have a good acquaintance among his students. I had made friends with Valery Karasyov, who had just made it to the All-Union team of USSR in 1964. He placed 12th in the preliminaries.

{Note: Elsewhere in his autobiography, Voronin mentions that Diomidov had a fight with Karakshyants, and it made him want to quit gymnastics altogether.]

He advised me to start training with my teacher Yevgeny Korolkov. I liked Korolkov because of his intelligence and calm. He had been a well-known gymnast, a meritorious champion athlete (Helsinki Olympics team gold and silver on rings, 1954 team world champion and silver on rings). Karasyov was his first champion athlete.

I spoke with Korolkov and went to train with him at “Zenit.” Sergei Diomidov and Volodya Soshin soon joined us. That is how our team came together.

I found myself in an atmosphere that I had been missing. We became friends immediately and we enjoyed being together. Yevgeny Korolkov was an amazing psychologist; he noticed the slightest change in mood, and he knew how to get me in the right mindset. It was pleasant to train with him; he never yelled, never argued, but it was impossible not to listen to him.

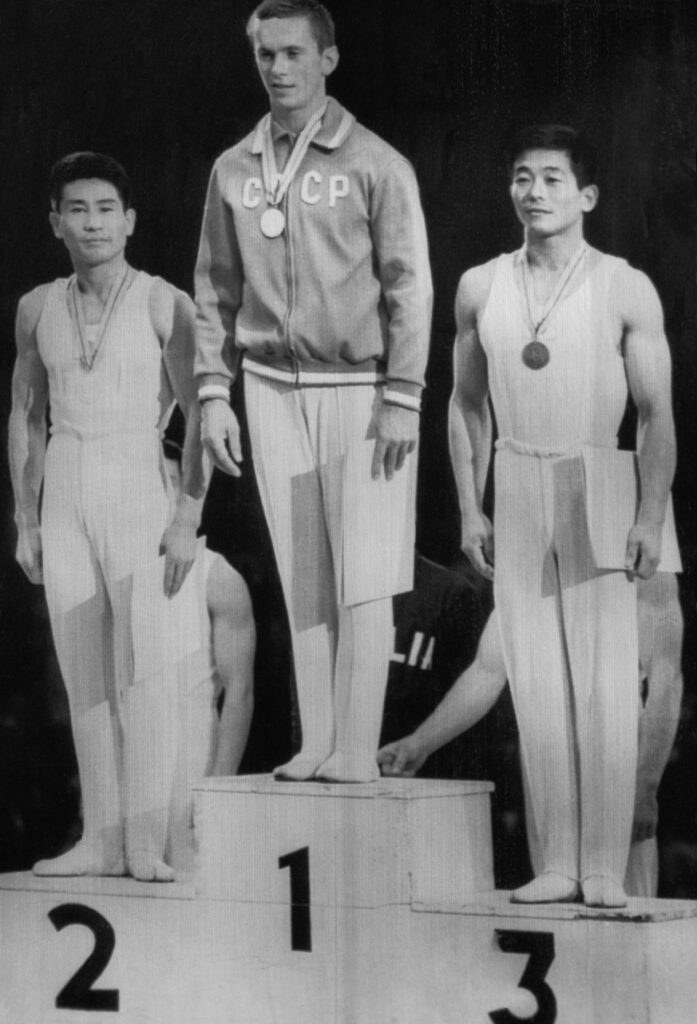

World Cup competitions. Sergei Diomidov became the world champion on parallel bars, Valery Karasyov participated on the team, I also got medals. What a joy! We were unrestrained in our training, and nothing could hold us back.

It is the year 1967. I am traveling to Tampere with Korolkov and Viktor Lisitsky for the European Championship competitions, I manage to win the cup; Viktor takes second place. In two months, the IV Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR. A tense battle with Karasyov for first place. At the end of the competitions, I manage to overtake my friend by a few tenths. Then came the foreign tours, competitions, demonstration performances…

A chain of successes. I enjoyed the fact that nothing came easily (I came, I saw, I won!), there were tense battles. The progress of our group was encouraging the coach, too. He gained confidence, defended his beliefs in the coaching council, argued, proved and was almost always opposed.

Yevgeny Korolkov was an advocate of classical gymnastics. He was never chasing difficulty, the tricks; he had been quite a stable and solid gymnast himself. Having become a coach and trained his students, he followed a straight path and was not inclined to experiment. He adhered to the old-school principles.

While preparing for the Olympic Games in Mexico, I noticed that Korolkov was not at all fond of learning new elements. He frequently recommended elements that were apparently outdated, but that, according to the code, were still highly rated. One or two elements we adopted, some were left out of the game.

I personally adhered to one rule: don’t show anything publicly until the element is completely refined. Spectators must not see substitutes, semi-finished products, or complete trash! Korolkov had the same point of view.

Each of us had our own plans for the Olympics, and we were trying to fulfill them. I realized that, in two years, gymnastics had progressed, and my routines were not difficult enough anymore. However, what I had prepared for Mexico was up to international standards. I wouldn’t have minded making the exercises more difficult in some areas, but my own heart and Korolkov told me that my style is not compatible with very high difficulty elements, that it is more like me to perform moderately difficult routines with academic rigor.

[Note: Sovetsky Sport criticized Voronin’s lack of difficulty during the Mexico Olympics.]

After Mexico, I went through some difficult days. The fact that I got a silver medal in the all-around was a severe blow to me. I should have won a big gold medal. But chance was at play, and it is the most unpleasant thing that can happen to an athlete. It was a severe blow to me.

I also started to receive criticism in the articles of specialists, all accusing me that the Olympic program was not difficult enough. As if I hadn’t received a lap full of medals, two of which were for first place in individual disciplines… The analysis of our performances was diverse, extensive, and very harsh. The team lost heavily to old rivals, the Japanese. Somewhat justifiably I came under fire as well.

Both what was published in the press and the stories of the coaches were distressing for me. Of course, I realized that, with exercises of that level of difficulty, I would not stay in the leading position for long. I was upset and terribly angry with Korolkov for holding me back when I was trying to learn particularly difficult elements. Something revolted in me, I longed for independence, I could no longer listen to anyone talking about putting together a simple routine. I decided to turn things around.

Yes, the Olympics left a deep mark on me. The tension was huge. I fought the Japanese alone, without the support of my comrades, and the increased responsibility drained me of all my mental and physical strength. The pain of loss was so great and humiliating that it shattered my faith in my own strength. And I began to hesitate, although outwardly it seemed that I was taking a decisive step, showing manhood by creating a preparation plan for the 1969 EC [i.e. European Championship] competitions.

Korolkov was lying in the hospital bed at that time. I, on the other hand, decided to work on the difficult elements. I wanted to update everything, all the exercises, because I understood that in gymnastics, without progress you cannot succeed, that would be equal to death.

I definitely had to learn double twists on floor, rings and high bar routines. The routine on the parallel bars also needed a comprehensive update. The boys were infected by my motivation.

[Note: You can see Voronin’s attempt at a double full on floor in this post.]

After a month, Korolkov got out of the hospital. I hadn’t told him anything when I visited him. He was surprised by the change of plans. The EC competitions were approaching and it would have been good to practice the old routines. And suddenly Yevgeny Korolkov saw that this plan was thrown far, far away…

The coach started arguing with me, at first calmly, but then more and more aggressively, that these stunts should be postponed until better times, that I wouldn’t be able to update the exercises and everything would fail. I, on the other hand, considered my way of acting to be correct, there was tension in the air…

Failure had sharpened my mind and feelings, the same had happened with Korolkov. I thought about the future and realized that something must be sacrificed for the bigger picture.

It seems to me, Korolkov was afraid to take risks. He convinced me that I would win the EC competitions with old routines, that I was still the best gymnast in the continent. However, I still wanted to take risks, push myself and start learning a new program for the World Cup competitions in 1970.

Our quarrel lasted a week. Those were hard days. I was very upset, as was the coach. However, one night we talked heart to heart, and I decided to give in. I backed off. I returned to the old routines.

Korolkov was right. In May 1969, I managed to become European champion for the second time in Warsaw with about the same routines I had done in Mexico. Korolkov celebrated the victory and I forgot about the fight. At that time I didn’t know that this cup would be my last highest prize, that my reconciliation with Korolkov would mean losing the World Cup…

[…]

«DÜNAMO» STAADION MINU TEINE KODU

Me elasime «Dünamo» staadioni lähedal. Isast jäin ilma, kui olin üsna tilluke, ja emal oli mind raske kasvatada. Palk oli väike, sest ta töötas koristajana. Nälga me ei näinud, kuid riides käisime kehvalt.

Koolis käisin meelsasti, õppimine läks mul libedalt, kuid suurema õhinaga lippasin «Dünamo» staadionile, kus tundide viisi sai vutti taotud. Talvel aga panin uisud alla ja tritsutasin nii palju kui süda lustis.

«Dünamo» staadion on terve maailm. Meile, poisikestele, sai ta teiseks koduks. Nägime tuntud sportlasi, imetlesime neid pärani silmi. Sportlased olid kuidagi isevärki rahvas lõbusad, sümpaatsed poisid, käisid moodsalt riides, mõnel neist oli auto. Aga treeningul olid nende särgid nii märjad, et vääna või vett välja, nägime kokkukleepunud juukseid, katkendlikku hingamist, väsinud pilke … Nad treenisid. Jah, nad treenisid ja meie imestasime, et see võib nii ränkraske olla.

Võimlemine mulle suurt ei meeldinud selles polnud mängu, hasarti. Kuid muskulatuur oli võimlejad suurepärane ja ma mõtlesin, et need poisid on väga tugevad.

Olin 13-aastane, kui tegin esimese argliku katse võimlemissektsiooni astuda. Treener vaatas minu kõhetut kuju, pikka peenikest kaela ja ütles ära. Ega see mind väga kurvastanudki, kuid ma käisin endiselt saalis vaatamas, mida see võimlemine endast kujutab.

Mulle tundub, et tol ajal nägin Sahlini esmakordselt. Oli see nüüd kinos või «Dünamos» treeningul. Täpselt ei mäleta. Siis mul tuligi kange tahtmine võimlema hakata ja ma tegin teise katse.

Meie kehalise kasvatuse õpetaja Konstantin Sadikov oli varem võimleja olnud ja juhatas nüüd sektsiooni. Torkasin talle silma kooli uisuvõistlustel. Mängisin juba «Dünamos» hokit ja tegin edusamme. Sadikov võttis mind sektsiooni.

Raske on meelde tuletada esimesi samme spordis. Näiteks mina ei mäleta, missugustest harjutustest me koolis alustasime. Võimlemisriistad paelusid, see oli huvitav, sest õnnestumised tulid üksnes suurte pingutustega.

ESIMESED TREENERID

Kolisime Stšukinosse. See oli küll kaugel, kuid oma Moskvakoolist ma ei lahkunud. Pärast tunde polnud tahtmist koju sõita. Läksin jälle «Dünamosse». Müttasin seal rööbaspuudel, rõngastel, hobusel, püüdsin midagi huvitavamat välja mõelda. Siis aga algas põhitreening. Vahel olin hirmus väsinud, aga seda ei tohtinud välja näidata ja ma püüdsin teistest poistest mitte maha jääda. Need lisatreeningud tõid suurt kasu: muutusin tugevamaks, sain teistest kiiremini uued elemendid selgeks.

Aasta pärast viidi meid üle Vitali Beljajevi rühma. Beljajev oli huvitav inimene. Noorusaastad oli tegelnud muusika, võõrkeelte ja spordiga. Astus Rahvusvaheliste Suhete Instituuti, aga ei lõpetanud seda sõda tuli vahele.

Siis hakkas treeneriks. Oli oma ametist fanaatiliselt sisse võetud, ei olnud tal õieti kodu ega perekonda. Oli ainult üks võimlemine. Ent ta polnud säherdune fanaatik, kes näeb enda ees ainult üht eesmärki: kasvatada ükskõik milliste vahenditega esivõimlejat. Ei, Beljajev oli teist sorti fanaatik. Ta oli juurdlev ja suurte teadmistega mees. Treeneritöö oli teda niivõrd haaranud, et loomerõõm ja otsingud neelasid täielikult tema eraelu.

Kui me tema rühma läksime, oli tal aastaid juba üle 40 ja tema käe alt oli sirgunud paarkümmend meistersportlast. Ta valis meid ise välja, tal oli andekate poiste peale harukordne nina. Ja nüüd algas hoopis teistsugune võimlemine …

Viis aastat oli Beljajev meile kõik. Me uskusime temasse, kuulasime tema sõna, meie õnnestumised olid tema õnnestumised ja paistis, et viimaks ometi naeratab talle õnn. Meie rühm oli selline: NSV Liidu noorte karikavõistluste hõbe Leonard Rõžkov, üleliiduline noortemeister Volodja Kokorev, NSV Liidu koondise liige Vjatšeslav Davõdov, paljudel rahvusvahelistel turniiridel osalenud ja Mexico OM-i varumees Volodja Sosin, meistersportlased ja Moskva esivõimlejad Miša Privess, Vitali Lomtev ja Jura Filippov. Me kõik õppisime koos Beljajevi juures.

«Veel veidi ja koondises on ainuüksi Beljajevi poisid,» kadestasid teised treenerid.

Ent läks teisiti. Meie rühm hakkas lagunema. Ja süüdi oli selles … Vitali Beljajev.

Me sammusime kindlalt meisterlikkuse astmeid pidi üles ja eakaaslaste hulgas meile vastaseid ei leidunud. Moskva ja «Dünamo» meistrivõistlused, teised turniirid kõikjal võidutsesid Beljajevi õpilased, sest nad võimlesid teistest erinevalt. Mõni esines halvemini, mõni paremini, aga igaüks demonstreeris kõrget klassi, tolle aja kohta väga raskeid kombinatsioone.

Beljajev oskas ja armastas lastega töötada. Ta oli mitte ainult treener, vaid pedagoog selle sõna parimas mõttes. Ta hoolitses meie eest nagu ema. Ma ei ütle, et ta poleks Õpetanud meile iseseisvust, sugugi mitte. Ent Beljajevi armastus muutus ajapikku pimedaks.

Me sirgusime, mõned olid juba 20-aastased, mina olin üheksateistkümnene. Aga Beljajev, nähtavasti pimestatud edusammudest, ei taibanud, et olime juba täiskasvanud, mehistunud. Nägin, kuidas ajapikku suurenes poiste rahulolematus, neile olid vastukarva alaealistele määratud karmid eeskirjad.

1965. a., kui sain NSV Liidu meistrivõistlustel teise koha, hakkas meie rühm lagunema. Kõigepealt läksid pärast konflikti ära Kokorev ja Rõžkov. Meie ümber juba tiirutasid igasugused metseenid, kavalpead treenerid, kes pakkusid poistele kõiksugu hüvesid ja soovitasid neil «totra fanaatiku» Beljajevi juurest ära tulla.

Siis lagunes rühm lõplikult. Beljajev lahkus «Dünamost» ja meie jäime omapead …

ÕLG ÕLA KÕRVAL

Mis sai edasi?

Plaanitsesin minna Konstantin Karakašjantsi juurde, kuid tema õpilaste hulgas mul head tuttavat ei olnud. Olin sõbrunenud Valeri Karasjoviga, kes oli just pääsenud üleliidulisse koondisse: NSV Liidu 1964. a. esivõistlustel sai ta 12. koha.

Tema soovitas mul alustada treeningut oma õpetaja Jevgeni Korolkovi juures. Korolkov meeldis mulle intelligentsi ja külma rahuga. Ta oli olnud tuntud võimleja, teeneline meistersportlane (Helsingi OM-i meeskondlik kuld ja hõbe rõngastel, 1954. a. meeskondlik maailmameister ja hõbe toenghooglemises). Karasjov oli tema esimene meistersportlane.

Rääkisin Korolkoviga ja läksin üle tema juurde «Zeniiti». Varsti ühinesid meiega ka Serjoža Diomidov ja Volodja Sosin. Nii kujunes meil rühm.

Sattusin atmosfääri, millest mul oli puudus olnud. Me sõbrunesime otsekohe ja meil oli koos hea olla. Jevgeni Korolkov oli võrratu psühholoog, tabas ära vähimagi muudatuse meeleolus, oskas mind häälestada. Temaga oli meeldiv treenida, ta ei käratanud kunagi peale, ei vaielnud, kuid võimatu oli tema sõna kuulamata jätta.

MM-võistlused. Sergei Diomidov tuli maailmameistriks rööbaspuudel, Valeri Karasjov tegi kaasa meeskonnas, ka mulle tuli medaleid. Oli alles rõõmu! Olime treeningutel ohjeldamatud ja miski ei suutnud meid tagasi hoida.

1967. aasta. Sõidan koos Korolkovi ja Viktor Lissitskiga Tamperesse EM-võistlustele, Mul õnnestub karikas saada, Viktor hõivab teise koha. Kahe kuu pärast NSV Liidu rahvaste IV spartakiaad. Pingeline heitlus Karasjoviga esikoha pärast, võistluste lõpus õnnestub mul sõpra mõne kümnendikuga edestada. Seejärel välisturneed, võistlused, demonstratsioonesinemised…

Õnnestumiste ahel. Meeldiv oli see, et miski ei tulnud lihtsalt (tulin, nägin, võitsin!) vaid palavates heitlustes. Meie rühma edusammud innustasid ka treenerit. Ta sai juurde enesekindlust, kaitses oma veendumusi treenerite nõukogus, vaidles, tõestas ja peaaegu alati tuldi talle vastu.

Jevgeni Korolkov oli klassikalise võimlemise pooldaja. Ta ei ajanud kunagi taga raskust, trikke, ta oli ise olnud üsna stabiilne ja kindel võimleja. Saanud treeneriks ja kasvatades oma õpilasi, sammus ta sirget teed mööda ega kaldunud eksperimenteerima. Ta pidas kinni vana kooli põhimõtetest.

Mexico olümpiamängudeks valmistudes märkasin, et Korolkovile polnud sugugi meeltmööda uute elementide õppimine. Pahatihti soovitas ta sääraseid elemente, mis olid ilmselt vananenud, kuid mida tabeli järgi hinnati veel kõrgelt. Üht-teist võtsime omaks, üht-teist jätsime mängust välja, mõnda tuli endal ette panna.

Mina isiklikult pidasin kinni ühest reeglist: enne mitte midagi avalikult näidata, kuni element pole täielikult lihvitud. Pealtvaataja ei tohi näha aseaineid, pooltooteid, käkerdist! Niisamasugune vaatevinkel oli ka Korolkovil.

Meist igaühel olid olümpiaks omad plaanid ja me püüdsime neid täita. Mõistsin, et kahe aastaga on sportvõimlemine edasi arenenud ja minu kombinatsioonid pole küllalt rasked. Kuid see, mida ma kavatsesin Mexicos näidata, vastas rahvusvahelistele standarditele. Mul polnuks midagi selle vastu, et mõnel alal harjutusi keerulisemaks teha, kuid süda ja Korolkov ütlesid, et minu stiil ei sobi kokku väga raskete elementidega, et mulle on omane akadeemiline rangus mõõduka raskusega kombinatsioonide piires.

Pärast Mexicot elasin läbi raskeid päevi. See, et sain mitmevõistluses hõbemedali, oli mulle ränk löök. Pidanuksin võitma suure kuldmedali. Aga juhus tuli vahele ja see on kõige ebameeldivam, mis sportlasel võib juhtuda. See oli mulle ränk hoop.

Hakkasin kõrvakiile saama ka spetsialistide artiklites, kes nagu kokkuräägitult süüdistasid mind selles, et olümpiakava polnud küllalt raske. Nagu ma polekski saanud sületäit medaleid, millest kaks olid esikohtade eest üksikaladel… Meie esinemiste analüüs oli mitmekülgne, laialdane ja väga karm. Meeskond kaotas suurelt vanadele rivaalidele jaapanlastele. Ja kriitikatule alla see oli üldjoontes õiglane sattusin ka mina.

Nii ajakirjanduses avaldatu kui ka treenerite jutud ängistasid. Mõistsin muidugi, et säärase raskusastme harjutustega ma kauaks liidrikohale ei jää. Olin endast väljas ja Korolkovi peale hirmus vihane, et oli mind tagasi hoidnud, kui üritasin eriti raskeid elemente õppida. Midagi lõi minus mässama, ma ihalesin iseseisvust, ma ei suutnud enam kuulda jutte lihtsast kavast. Otsustasin plaadil teise poole pöörata.

Jah, olümpiamängud jätsid minusse sügava jälje. Närvipinge oli tohutu. Heitlesin jaapanlastega üksinda, kaaslaste toetuseta ja sellest suurenenud vastutus pitsitas minust välja kogu vaimu- ja kehajõu. Kaotusevalu oli nii suur ja alandav, et põrmustas usu oma jõusse. Ja ma hakkasin kõhklema, kuigi väliselt näis, et teen otsustava sammu, näitan üles mehisust, kavandades 1969.a EM-võistlusteks ettevalmistuse plaani.

Korolkov lamas sel ajal haiglas. Mina aga asusin otsustavalt raskete elementide kallale. Ma tahtsin kõike uuendada, kõiki harjutusi, sest sain aru, et progressita ei saa võimlemises läbi, see oleks võrdne surmaga.

Pidin ilmtingimata kätte õppima kahekordsed piruetid vabaharjutustes, rõngastel ja kangil. Põhjalikku uuendust vajas ka kombinatsioon rööbaspuudel. Poisid nakatusid minu hasardist.

Kuu aja pärast tuli Korolkov haiglast välja. Teda külastades ei olnud ma rääkinud talle midagi. Talle oti plaani muutmine ootamatu. Lähenesid EM-võistlused ja tulnuks rahulikult korrata vanu kombinatsioone. Ja äkki nägi Jevgeni Korolkov, et see plaan on aia taha visatud…

Treener hakkas mulle tõestama, algul rahulikult, siis aga üha keevalisemalt, et need vigurid tuleb paremaid aegu ootama lükata, et ma ei jõua harjutusi uuendada ja kõik lendab uperkuuti. Mina aga ajasin oma jonni, sest pidasin oma talitusviisi õigeks, õhus hõljus tüli…

Ebaõnnestumine oli teritanud minu mõistust ja tundeid, sama oli sündinud ka Korolkoviga. Ma mõtlesin tulevikule ja mõistsin, et suurele tuleb väike ohvriks tuua.

Nagu mulle tundub, kartis Korolkov riskida. Ta veenis mind, et võidan EM-võistlused ka vanade kombinatsioonidega, et olen endiselt maailmajao parim võimleja. Ent mina tahtsin siiski riskida, enesest võitu saada ja 1970. a. MM-võistlusteks hakata uut kava õppima.

Meie tüli kestis nädala. Need olid rasked päevad. Olin endast väljas, ka treeneril oli närv must. Ent ühel õhtul rääkisime teineteisele ära, mis meil südamel, ja ma otsustasin järele anda. Taganesin. Naasin vanade kombinatsioonide juurde.

Korolkovil oli õigus. 1969. a. mais õnnestus mul Varssavis tulla teist korda Euroopa meistriks. Umbes samasuguste kombinatsioonidega, mida ma Mexicos teinud olin. Korolkov pühitses võitu. Ka mina unustasin tüli. Kuid siis ma veel ei teadnud, et see karikas jääb minu viimaseks kõrgeimaks auhinnaks, et minu leppimine Korolkoviga tähendab kaotust MM-võistlustel…