At the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, both Voronin and the Soviet team took silver. In Voronin’s 1976 autobiography titled Number One (Первый номер), he underscores that 1968 was a low point for him:

Yes, the [1968] Olympics left a deep mark on me. The tension was huge. I fought the Japanese alone, without the support of my comrades, and the increased responsibility drained me of all my mental and physical strength. The pain of loss was so great and humiliating that it shattered my faith in my own strength.

Jah, olümpiamängud jätsid minusse sügava jälje. Närvipinge oli tohutu. Heitlesin jaapanlastega üksinda, kaaslaste toetuseta ja sellest suurenenud vastutus pitsitas minust välja kogu vaimu- ja kehajõu. Kaotusevalu oli nii suur ja alandav, et põrmustas usu oma jõusse.

And he places the blame squarely at the feet of Valentin Muratov, the head coach of the Soviet team at that time. To support his point, Voronin highlights the misleading overscoring at domestic meets, the bizarre line-up order that upset both Voronin and Diomidov at the Olympics, Muratov’s insults, and the failure to block Kato Sawao’s 9.90 on floor exercise, where Muratov was the head judge at the Olympics.

At the same time, Voronin does conclude that the Japanese gymnasts were better and that the Soviet team’s expectations were off. The USSR thought that they had caught up to the Japanese team, but in reality, they were far behind.

Note #1: You can see a Soviet clip on Muratov here.

Note #2: Chapters of Voronin’s book were translated into Estonian for the newspaper Spordileht, and I have translated the chapter from Estonian into English. The following excerpts come from the January 16, 1978, January 18, 1978, January 23, 1978, and January 25, 1978 issues of Spordileht.

Note #3: This section of Voronin’s book responds to criticisms found in the pages of Sovetsky Sport, the main sports newspaper of the Soviet Union. You can read the newspaper’s coverage of the Soviet men in Mexico City here.

Chapter III

WHEN THERE IS NO CONSENSUS

I want to discuss the Mexico Olympic Games, because these Olympic Games turned out to be the touchstone with which we still try to keep our attitude towards gymnastics and the people around us in check.

…When we arrived in Mexico and trained there, I had a premonition of luck. I was wandering along the noisy and also the quiet streets, went to shops, on sightseeing trips, sat willingly in the Olympic village’s interclub in the evenings. And I couldn’t understand: what was wrong with me? I even glanced in the mirror. It was my face, the same as always: sunken cheeks, deep-set eyes, a slightly tired expression… But still, something was different.

The heat was relentless and agonizing. The boys trained sluggishly. But it was only like that at the beginning; later on we adapted. To be honest, I don’t want even for my enemy to go through the feeling that an athlete has before the start of the competition. You admonish yourself: “After all, you’re not a boy! You’ve been competing for a hundred years, this is your job, and you can’t think too much about the future. You have to eat, drink, sleep, go to the gym properly, have fun, and that’s it! You have to know how to be a robot for these two weeks. And to calmly go to the gym floor and be the same as always, just like training. Nothing more is required of you…”

This is probably the reasoning of most athletes. But even with the help of intelligent self-affirmation, you cannot escape the completely natural, very unpleasant nervousness. I don’t believe those who say they don’t get nervous. Not possible! Or you’re not an athlete. It means they don’t care about their field, if they’re winning or losing.

Sometimes I feel that I could win with no problem. I feel my power, my superiority. But I still experience that nasty pre-competition fear. Why don’t many coaches’ dreams come true? Why don’t some great athletes last? They burn out like comets in the sky, their nervous system burns out, worn out by the days and hours leading up to the launch.

I don’t know about others, but I made a huge effort to reduce these feelings of fear. Not to brag, but it seems to me that I did find the cure for this anxiety at the first competitions. Above all, willpower was needed to create a state of balance. For this, I came up with nightly relaxation exercises. I hardly kept a diary then, I was too excited to make calm notes. Now, of course, I regret it.

I was considered the only favorite, the first contender. In the two years since Dortmund, I had not lost a single competition, either at home or abroad. Among my own team, I only had two serious competitors, Sergei Diomidov and Viktor Lisitsky. Later, Viktor Klimenko started to stand out, but he was young and inexperienced and remained a bit in the background. After the World Championships, I managed to win at the European Championships in Tampere, at the IV Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR, at all international meetings, the fame of being the world’s leading gymnast firmly stuck to me.

Was I aware of my superiority? Yes, I was! Was I afraid of the Japanese? Of course, I was afraid, but I felt that my chances were more favorable. Faith in my strength was strengthened when Diomidov defeated Nakayama Akinori and Kato Sawao during the Olympic week in Mexico. I did not take part in those major competitions due to strategic considerations: it was not practical to meet the main rivals before the main battle at the Olympic Games.

[Note: At the time, it was reported that Voronin had injured his shoulder in training at the Little Olympics in Mexico City in 1967.]

After watching the film made during the pre-Olympics, I realized that the Japanese masters did not prepare any special innovations or striking elements. Of course I understood that they could be tricking us. But we are not so stupid that we don’t understand what is going on. From the general direction of their exercises, it became clear that they were in the process of sharpening their skills. They had fixed the difficulty to a certain level, and all attention was now directed to the purity of the performance. In short, the Japanese had decided to use my own weapon against me.

[Reminder: Voronin and Korolkov, his coach, decided to do simple routines cleanly.]

What did I know about the Japanese!? Everything and nothing. Our coaches had studied them for several years, had visited Japan countless times, had translated Japanese literature, and found out their training methods. But the Japanese still remained a mystery to us. Japan’s most famous gymnasts Takemoto Masao, Ono Takashi, Nitsukuri Suzuki,* Endo Yukio, Kato Sawo, Nakayama Akinori, Tsukahara Mitsuo, Kenmotsu Eizo … They all had similar smiles, bows, they all were smiling and pretended to be simple-minded. And no one really knew their character, habits, inclinations, interests. It was all hidden from us, locked away. They were virtuosos of the highest order, but on the gymnastics floor, they sometimes slipped; none of them resembled the great Shakhlin. The best Soviet gymnasts have wrestled with the Japanese, and often successfully.

[*Potentially, Nitsukuri Suzuki is Mitsukuri Takahashi.]

At the Mexico Olympic Games, Nakayama and Kato were the strongest of the Japanese. Nakayama seemed better. His all-around program was perfect, except for pommel horse. My goal was to become an Olympic champion. And not just a winner, but an all-around winner. It is the most respected title in gymnastics. Was I overconfident? It seems not. By all objective measures, my prowess had not faded compared to Dortmund. What had I successfully developed in my technique? I had strengthened and updated the combinations in the optional routines on pommel horse and high bar.

My exercises were of international level. So essentially, everything was up to willpower, nerves, and determination. But I had no problem with that.

I was prepared to win.

TACTICS AND “STRATEGY”

Things were more complicated with the team. In the spring of the Olympic year, after the All-Union championships in Leningrad, everyone started saying that we finally have a team that is able to successfully compete with the Japanese. This idea was persistently encouraged by head coach Valentin Muratov in his interviews, it was written about by newspapermen, it was confirmed by our gymnastics managers.

These opinions were valid. By 1968, the young Viktor Klimenko, Valery Iljinykh, and Vladimir Soshin had emerged. But at the top were the experienced Diomidov, Lisitsky, Karasyov, and me. There weren’t exactly a lot of Olympic candidates, but what competitors!

In Leningrad, these seven leaders were brilliant. Scores of 9.7, 9.8, and even 9.9 were crowning our work. Remembering those competitions now, I just marvel at how well the boys performed with soul, with fury, with beauty. At that time, it seemed to me that the heyday of men’s gymnastics was really here. The spectators were cheering, and we were all proud of it.

However, the core of the matter was that it was decided to make a “smart psychological move” at the championships. To deceive the Japanese, or rather not to deceive, but to frighten them. That’s why high scores came like a cornucopia. By the way, only the scores of the men who were being considered for the team were increased.

In Gorki, at the USSR Cup, where I did not participate, the scene was the same. This psychological trick was nothing new. It had already been used in the All-Union Championship before the Tokyo Olympic Games. But the witty ploy did not justify itself. The Japanese had also used it before. For example, let’s say you open a newspaper and read the results of the Japanese championships. Gymnasts have such high scores in the all-around that it would be wise to give up on the World Championships, there would be no shot anyway. The trick went through once, but the second time, we no longer paid attention to the results. The score is not what’s important; it is the visual comparison of craftsmanship. As we found out in Mexico, the judges didn’t care about our admirable totals at all. They wanted to see the goods for themselves.

But we did not consider the changed situation and were in favor of the “strategy.” Unfortunately, it hurt us a lot. Especially the young people who were Olympic Games debutantes. The boys were proud of their high totals, but at the same time full of confusion and didn’t know which result could actually be counted. How to distribute your energy?

This is how the competitors at the All-Union champions who had high, even maximum scores in individual diciplines, did not get to the finals in Mexico, and if they did, they could not offer competition to foreign athletes. The ability to evaluate one’s strength and abilities was lost in the Olympic year. These experiments were later condemned.

But I rushed ahead.

However, we got the team together. Everyone had high-difficulty routines, good class and a desire to win. But there was something rotting in the team that no one had noticed yet. It was being fuelled to grow and develop from the unhealthy relationships that arose in the team.

Valentin Muratov was an outstanding gymnast. He had already given up competitive sports when I started, but I managed to see him on the cinema screen. Muratov was the most elegant gymnast, he created the “elegant calligraphy” style of movements. He was strong-willed, energetic, an unparalleled expert in his field, and from 1961, he began managing the team. He knew a lot, he learned to efficiently lead people, and his authority grew year by year.

After a devastating defeat at Tokyo Olympics, where only Boris Shakhlin managed to get a gold medal on high bar, my becoming the all-around world champion in Dortmund was a complete surprise. Could it be possible that the debutant Voronin could win in the all-around?

I noticed how Muratov began to claim more and more often that my victory was planned. It is understandable that the revolution in our gymnastics happened not only by the will of one person, but was due to objective inevitability. In December 1964, everyone saw a new leap in quality, the appearance of young competitors with a new direction. And the success of Voronin and Diomidov in Dortmund was the result of a change of generations, substantial changes. However, Muratov gradually began to emphasize that success was owed to the right tactics and a skillful leadership.

[Note: You can read about the USSR Championships from 1964 here.]

When the team was more or less certain, Muratov began to tighten the screws, requesting that everyone listen to him without question. As everyone knows, working with people requires great tact. If a person starts to oppose himself on others, he will soon be isolated. Muratov was the coach of our gymnastics team for quite a long time, and he was convinced of his inability to be wrong. Yes, discipline is needed, strictness is needed, and violators of discipline must be punished. But it seems to me that Muratov went too far, he insulted the boys unnecessarily.

On the one hand, Muratov was a fun, smart, pleasant, and friendly person, an excellent organizer, a courageous and knowledgeable coach. On the other hand, Muratov could be overly sharp. Having concentrated power in his hands, he did not listen to others and made his decisions independently.

Yes, Muratov was respected. I had quite a normal relationship with him. But over time, all the boys began to notice that the senior coach had poor composure. His behavior was hard to watch. Sometimes he whispered to one, sometimes to the other, he publicly punished those who did not follow his instructions. At that time, I thought that the coach’s actions were not up for debate. Only now do I understand that Muratov was just full of himself, but no one told him that. Too bad! He caused discord among the boys.

Muratov had particularly strong clashes with Diomidov, an athlete with a difficult character, who should be approached in a different way.

Muratov, a far-sighted gymnastics specialist, thought that we would not be able to defeat the Japanese as a team anyway, but he kept encouraging a version of the unprecedented strength, unity and high skill of the Soviet Olympic team. We were all tuned in for a relentless battle for first place, but Muratov thought otherwise. He had decided to defeat the Japanese in the individual events, to try for gold medals here.

CONFLICTS…

The Olympic team consisted of six members and one reserve. Diomidov, Karasyov, and Soshin were training under Yevgeny Korolkov. Klimenko, Lisitsky and Iljinykh were taught by Konstantin Karakashyants. Korolkov was considered a young coach, he had only trained Karasyov and a few master athletes. Karakashyants was an outstanding coach, whose students included dozens of master athletes and well-known gymnasts Valentin Muratov, Viktor Lisitsky, Yuri Stoida, Viktor Klimenko. You probably already guessed that Muratov felt a special sympathy for his coach and supported him in every way.

Before Mexico, Diomidov and I were considered the leaders of the team. Sergei was the world champion on parallel bars, had beaten the Japanese in the exhibition games and during the Olympic week, and he had won the USSR Cup in Gorki [in July of 1968].

At the All-Union Championship in Leningrad, young Klimenko and Iljinykh had a successful start, and they had difficult exercises. Their attack was furious, everything seemed to be easy for them. I enjoyed their performances. But I considered Viktor Klimenko a gymnast with a great future.

This time I didn’t make predictions about Valery Iljinykh. He was nervous, very irritable, prone to arrogance. He was terribly afraid of competitions, blushing and nervous beforehand. But in Leningrad [at the USSR Championships in May of 1968], Iljinykh was on a roll; neither before nor since has he performed better.

However, the success of Iljinykh and Klimenko was also somewhat wrongly assessed. Muratov, leading the appeal jury, gave tips to the judges on the way. We, on the other hand, were quite perplexed, or rather outraged, that these young gymnasts were apparently given overscores (although, as I have already said, the scores of all competitors were raised). And it turned out that they were given the starring roles.

At that time, it seemed to us that Muratov was doing everything to get Karakashyants’ students to lead. Korolkov shared that vision. In essence, in Leningrad and Gorki, groups — not athletes — competed. Korolkov and Karakashants ran from one judge to another, keeping an eye on each other. They almost lost their temper. We were nervous too. All it took was a spark to start a conflict. Everything seemed to be calm on the outside, the bystanders did not notice anything. High scores, sensation (the unknown Iljinykh gets a gold medal on the pommel horse!), the enthusiasm of the hall, all this was remarkable. But only the participants of the events knew what kind of nerve these Olympians needed.

To be honest, I watched it all at a distance. After all, I was emphatically singled out from among others (do not get me wrong, this is not bragging, but a sober assessment of important events. That’s why I try to be as objective as possible).

Before leaving for Mexico, Muratov proposed an idea of how, according to him, to place the men in the national team. It is known that the leader enters the competition last. The judges’ scores, as is the tradition in gymnastics, improve one after the other, and the last, strongest athlete gets the best score.

Of course, this is only true if the performance is impeccable. Muratov presented such a team sequence that angered Korolkov. Diomidov was essentially out of contention for first place in the all-around competition. He was number three or four on some events. This was a psychological stab.

Diomidov’s mood fell terribly, he became sullen. I wasn’t always put last either. I realized that Muratov does not believe in me either …

What a scandal broke out in the coaching council! Korolkov claimed that Voronin is the only man who can and must win in the all-around, that Diomidov has great authority among the judges, that his victories in recent years promise a worthy competition with the Japanese…

Karakashants talked about the growth of young people, their interesting routines that win over the judges, and that only they can get medals in individual disciplines…

The arguing affected the mood of the coaches and competitors. Yes, those were dark days…

Perhaps you are interested in the opinion of G. Baklanov, the chairman of the All-Union Gymnastics Federation. The answer: he supported Muratov. I need to talk a little more about Gleb Baklanov. He led the federation in a difficult time and did a lot of useful things for the development of gymnastics. However, in my opinion, Baklanov also made mistakes. He was an advocate of military discipline on the team.

[Note: Baklanov was a Soviet Army colonel general. Hence the military reference.]

He ordered the coaches to organize training in such a way that he could check with a stopwatch. He didn’t like when there was clamoring, joking around, or resting during training. He felt that we did not know how to walk properly, and he even started to teach us the correct soldier’s posture and how to walk. He did not care about the requirement of an individual approach to the athlete. With this, he supported Muratov and gave him free rein.

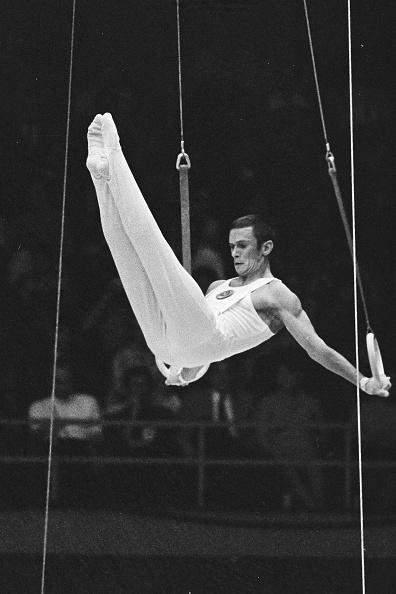

I remember, once Gleb Baklanov came to the training hall of “Dynamo.” After watching for a while, he then came up to me and started to explain that I had swung on the rings incorrectly. By the way, at that time I had been the world champion on this apparatus for more than a year. Then Baklanov made a remark about how I bend my leg in one element. I gently explained to him that sometimes something doesn’t work out during training and then you have to repeat elements or routine until something finally dawns. I was a little uncomfortable. Korolkov too. But it seemed to Baklanov that he had helped me and the coach…

My words may sound too sharp, maybe even disrespectful. Please understand, I do not wish to smooth out the sharpness. I am not saying this to offend anyone. Not at all! I am talking about the years that I think were difficult for our gymnastics.

I am speaking about this so that these mistakes will not be repeated in the future. “How much evil can be eliminated with openness!” F. Dostoevsky said.

At that time, a theory emerged, which I called the “theory of total secrecy.” Baklanov didn’t like it at all when something was reported about us in the press. It seemed to him that the journalists were revealing in their stories the secrets of our athletes — secrets that the Japanese must not know. He advised journalists to be even more secretive, to talk about the fact that Soviet gymnasts are using new training methods, learning never-before-seen elements. Baklanov thought that all this would frighten our main rivals.

Once, Baklanov called one of the correspondents to him and scolded him for writing a report on the training of the Olympic team. The journalist had simply told about a busy and interesting training day. By the way, that report talked about me, Diomidov, Karasyov, and Soshin. Baklanov reproached the penman for writing too openly and revealing all our cards to the Japanese.

What a shame that Baklanov and Muratov pursued such a harsh policy towards us. I emphasize, the point here is not in strengthening discipline (which is necessary), but in the unfriendly relations that arose between the management and the athletes.

… Thinking of the mission that had befallen me, I devoted my life from Dortmund to Munich to the single goal of victory at the Olympic Games. However, a spark of doubt was ignited on the very day when I found out how the men in the national team were put in order.

“So we are not considered the strongest? You mean they don’t believe in me?” I thought to myself anxiously. In those days, my coach gave me support. His firm faith, his intuition not to notice this sudden attack of thoughts, his long conversations helped. I regained my peace of mind. But not for long. Until the start of the Mexico competition.

A FATEFUL COINCIDENCE?

… Such was the situation in our national team on the threshold of the XIXth Olympic Games. Complicated. On the one hand, many believed in our victory, in my victory; on the other hand, the unhealthy atmosphere in the team, the quarreling between the coaches, the policy of the head coach, which, strangely enough, was aimed at deepening these contradictions. Why did Muratov need it? Or was he just anxious? No, I don’t think so. He is not the kind of man who would lose his head… He had simply lost his power over people and was now trying to regain his authority through the use of these methods.

What came of it all? Well, the results of the gymnasts in Mexico are known to everyone: the team lost to the Japanese by 4.8 points (there had never been such a big defeat before), I got second place in the all-around, Viktor Lisitsky and Valery Iljinykh performed below their abilities (14th and 15th place), Diomidov and Klimenko made rudimentary mistakes and did not show enough stamina, but each got a bronze medal. I managed to collect 2 golds, 2 silvers and one bronze in individual events.

What happened?

After the compulsory routine, I was 0.3 points ahead of Kato Sawao. At the same time, I was the last competitor only two times out of six. How much did I lose due to wrong tactics? A couple of tenths for sure…

Yes, I was betting on the compulsory routine. The reason was as follows. After the World Cup competitions, after the European Championships in Helsinki, where I won the gold cup, after numerous trips abroad, I could have stopped trying, and let everything unfold on its own. You can’t perform beyond your capabilities anyway. Whatever will be will be. One could argue that. And my conscience would have been clear because I had worked hard, and no one could have accused me of laziness.

However, thoughts of the Olympic gold medal had not given me peace for two years. Being an Olympic champion is something special, it is the greatest success in sports. I thought: if I have already been so lucky in life, then I must also pursue it in sports. That’s why I was excited for Mexico. I was really looking forward to it.

I did well in the Olympic compulsory routine. This had been confirmed by numerous competitions. There was not a single mistake anywhere. I refined and refined my routines and almost achieved virtuosity. It seemed to me that I had learned the exercises in such a way that they could not have been performed with more precision. After the All-Union Championship held in Leningrad, where everything went smoothly, I realized that I could win in Mexico. I believed in my power to do that.

Kato Sawao fell 0.3 points behind. Kato, who was considered the purest performing Japanese gymnast. Therefore, the judges liked me, they liked my style.

Do you think I was carefree and content? Far from it! The scariest part was still ahead, the most difficult is to maintain the gained lead. My teammates were behind me, the Japanese surrounding me. A fierce battle was expected.

The competition for first place in the team was essentially over on the first day. All that was left was to fight for the individual medals. The tension was huge, but everything worked out. Kato couldn’t catch me, and I was still in the lead before the last event.

Our team’s last event was pommel horse, for the Japanese it was floor exercise. I wasn’t nervous. All I felt was anger. Good anger. I began.

I wasn’t tired at all yet, I could feel every muscle. I liked the horse, I knew it well, and it had never let me down. But on this occasion… Yes, my finger got caught on my pant leg. Error. A momentary stop, but it cost me 0.3 points.

I finished the exercise perfectly. I saw Korolkov’s sullen eyes and forced smile. He was speechless. He turned to look at the boards. I sat on the chair. I was also staring at the boards. There wasn’t a single thought in my head. Just the anticipation.

9.5. Good and bad. After all, I made a mistake and was deducted for it. It could have been 9.7 or 9.8

I was slowly starting to recover. I remembered how my finger got stuck in the trouser leg. How could this happen? I don’t understand! Such a thing had never happened before … I had no choice but to wait for Sawao Kato’s performance.

Kato did great. But not without flaws. There were small slips here and there. I would say 9.7 points. Maybe I’m not being objective? Okay, let’s put it at 9.8. No more than that. That would be too much.

The scoreboard lit up with 9.9. I couldn’t believe my eyes. 9.9? How so? Where is the conscience of the judges? What was Valentin Muratov thinking? After all, he was the judge of the optional routines. He had the right to gather the judges and ask why they did not lower the mark for mistakes. Alas, Muratov did not.

They were calculating the points. Kato passed me with 0.05. This is the most insulting thing in sports! A mere five hundredths robs you of the all-around champion’s gold medal…

To be honest, I shouldn’t have lost. To this day, I still don’t understand how my finger got stuck in the pant leg. If I had fallen, bent my legs, messed up the element, I would have only myself to blame.

But such nonsense! What was I punished for? For what? That night I almost lost my mind. My eyes were full of shame, and my will to live was gone. I hid the silver medal at the bottom of the suitcase (why didn’t I throw it away, what was holding me back?). It hurts to admit, but I cried like a girl into the pillow that night. It was too much. Then I fell into a deep sleep.

By morning I felt sane again. The fit of despair had passed. I was a person again. It was confirmed: I must definitely become an Olympic champion. The individual finals were ahead.

Gymnastics fans should know how that turned out. I got gold medals on vault and high bar, silver on rings and parallel bars, and bronze on pommel horse.

WHO WAS STRONGER?

After Mexico Olympic Games, a discussion broke out in the columns of Sovetsky Sport. The discussion was about the reasons for our team’s defeat. I already talked about psychological reasons and tactics. I consider it necessary to draw attention to the technical side of the matter as well.

Be that as it may, Mexico Olympic Games forced coaches (and athletes) to make important changes in the training system.

So, we are quite interested in: a) which new trends were represented by the Olympic winners and medalists; b) what steps were taken by famous (and unknown) gymnasts in order to win prizes; c) what was the lesson for Soviet gymnasts.

In order to answer these questions, it is first necessary to clarify whether something fundamentally new was performed at the Auditorio Nacional. I can honestly answer no.

Before the Olympic Games, there were fierce disputes about how the “rule of three tenths” affects the difficulty level of the routines. I will explain this rule.

[Note: You can find the 1968 Men’s Code of Points here.]

In the individual events final, the judges assessed the gymnasts’ mastery not out of 10 points as usual, but out of 9.7. The judges could add 0.1 to this score for risk, originality and virtuosity.

The “0.3 point rule” forced the best gymnasts in the world to rethink their exercises. As the competitions showed, they had placed the main emphasis on purity of performance, virtuosity, and originality of the exercises. The Japanese routines were somewhat more difficult than ours, but that did not give them an advantage. They were also more original than ours.

The Japanese had interpreted the “0.3 point rule” correctly. In terms of difficulty, their exercises were impeccable, but the routines stood out precisely because of their uniqueness, they were not templated. This was fruitful.

What were the shortcomings of our gymnasts? Let’s look at the results of the finals (I’m using diary notes already made in Mexico).

FLOOR EXERCISE. There were 5 Japanese in the final six in this event. Valery Karasyov finished 5th.

Floor exercise is called the monopoly of the Japanese: here they are virtuosos. My teammates’ routines had plenty of difficult elements, but they were uninteresting in terms of form. They were built according to the classical scheme. The Japanese were not as conservative. We realized that we have fallen behind here, but not hopelessly.

VAULTS. In Tokyo, H. Yamashita performed a new vault. It was named after him. Soon everyone learned this vault, and no one wanted to invent anything new. In Mexico, gymnasts had to perform two vaults. Not many were ready for that. I think both attempts turned out pretty well for me. First place was given to me. Diomidov was third. The Japanese were poor in this event.

RINGS. After the departure of Albert Azaryan, the laurels went to T. Hayata in Tokyo and A. Nakayama in Mexico. Two years ago in Dortmund, I had won on rings. Basically, I could have gotten first place now as well: Nakayama’s lead was trivial. Four Japanese and two of us, Diomidov was sixth. Distinctive? Yes. They were stronger than us in terms of physical training, they had more beautiful high-difficulty elements. There were no new finds, but their performance was unparalleled.

PARALLEL BARS. Nakayama won. Convincingly! I got second place, Klimenko was third. And still, the performance of the Japanese was more interesting and diverse. Out of all of us, only Klimenko had a promising routine.

HORIZONTAL BAR. I shared first place with Nakayama. To be honest, I didn’t expect to win on this apparatus, but apparently the judges liked me, and everything turned out beautifully for me in the final. Nakayama and the other Japanese routines blew me away. They are way ahead of us here.

POMMEL HORSE. The Japanese have always had trouble with the horse. That’s their worst event. Among them, only one, Kenmotsu, (5th place) made it to the finals. Klimenko was sixth, I was third. Yugoslavian Miroslav Cerar won; he was also first in Tokyo. He didn’t show anything new. Diomidov, Lisitsky, and Klimenko presented several new elements, but there was no reaction to it. True, they weren’t sure. Just like me. In general, however, we have potential on horse.

…So. Before Mexico, we thought we had caught up with the Japanese, but in reality we were actually behind them. We were stronger than ever, but the Japanese were even stronger. Something needs to be thoroughly rearranged.

III peatükk

KUI ÜKSMEELT POLE

Tahan lähemalt peatuda Mexico OM-il, sest need olümpiamängud kujunesid selleks katsekiviks, millega me praegugi püüame kontrollida oma suhtumist võimlemisse ja ümbritsevatesse inimestesse.

…Kui me Mexicosse jõudsime ja seal treenisime, haaras mind õnne eelaimus. Uitasin mööda kärarikkaid ja ka vaikseid tänavaid, käisin poodides, tegin huvireise, istusin õhtuti meelsasti olümpiaküla interklubis. Ja mitte kuidagi ei suutnud mõista: mis minuga ometi lahti on? Heitsin isegi pilgu peeglisse. Oleks justkui tavaline nägu, seesugune nagu alati: sisselangenud põsed, sügaval istuvad silmad, veidi väsinud ilme … Aga ikkagi oli midagi teistmoodi.

Kuumus oli halastamatu ja me suisa piinlesime. Poisid treenisid loiult. Kuid see oli vaid alguses nii, hiljem saime õige rütmi kätte. Kui ausalt öelda, siis ma ei soovi oma vaenlaselegi läbi elada seda tunnet, mis valdab sportlast enne võistluse algust. Manitsed ennast: «Lõppude lõpuks ei ole sa ju poisike! Sa võistled juba sada aastat, see on sinu amet ja ülepea ei tohi mõelda eelseisvale. Tuleb süüa, juua, magada, korralikult võimlas käia, meelt lahutada ja kõik! Tuleb osata need kaks nädalat robot olla. Ja minna rahulikult võimlemispõrandale ning olla nagu alati, nagu treeningul. Rohkem sinu käest ei nõutagi…»

Küllap umbes niimoodi arutleb enamik sportlasi. Kuid isegi aruka enesesisenduse abil ei pääse täiesti loomulikust, väga ebameeldivast närveerimisest. Ma ei usu neid, kes väidavad, et nad ei närveeri. Seda ei saa olla! Või siis ei olda sportlane. Tähendab, tegevusala ei huvita, on ükspuha võit või kaotus.

Mul on olnud vahel tunne, et võin võita nagu muuseas. Ma tundsin oma jõudu, üleolekut. Ent ikkagi kogesin seda vastikut stardieelset hirmu. Miks ei saa teoks treenerite paljud unistused? Miks ei jää mõned suured sportlased püsima? Nad põlevad läbi nagu komeedid taevas, põleb läbi nende närvisüsteem, mis kulub just nende stardieelsete päevade ja tundidega.

Ma ei tea, kuidas teised, aga mina tegin hiigelsuuri pingutusi, et seda hirmutunnet taandada. Ma ei kavatse ärbelda, kuid mulle näib, et ma siiski leidsin juba oma esimeste võistluste aegu rohu stardipalaviku vastu. Eelkõige oli tarvis tahtejõudu, et luua tasakaaluseisundit. Ma mõtlesin selleks välja igaõhtused lõõgastusharjutused. Päevikut ma siis peaaegu ei pidanudki, olin rahulike ülestähenduste tegemiseks liiga erutatud. Praegu on mul sellest muidugi kahju.

Mind peeti ainukeseks favoriidiks, esimeseks pretendendiks. Kahe aasta jooksul pärast Dortmundi polnud ma kaotanud ühtki starti ei kodu- ega ka välismaal. Omade hulgas oli mul ainult kaks tõsist konkurenti Sergei Diomidov ja Viktor Lissitski. Hiljem tõusis esile Viktor Klimenko, aga tema oli noor, kogemusteta ja jäi veidi tagaplaanile. Pärast MM-võistlusi õnnestus mul võita EM-võistlustel Tamperes, NSV Liidu rahvaste IV spartakiaadil, kõigil rahvusvahelistel kohtumistel ja maailma juhtvõimleja kuulsus jäi mulle kindlalt külge.

–

Kas ma teadsin oma üleolekut? Jah, teadsin! Kas kartsin jaapanlasi? Muidugi kartsin, kuid tundsin, et minu šansid on eelistatavamad. Usk oma jõusse tugevnes siis, kui Diomidov võitis Mexico olümpianädalal Akinore Nakayamat ja Sawao Katot. Mina neil suurvõistlustel strateegilistel kaalutlustel kaasa ei teinud: polnud otstarbekas peakonkurentidega enne kohtuda, pealahing tuli pidada olümpiamängudel.

Vaadanud läbi eelolümpial vändatud filmi, sain aru, et jaapani meistrid erilisi uuendusi ega rabavaid elemente ette ei valmista. Muidugi mõistsin, et nad võivad udutada, kärbseid pähe ajada. Kuid ega meiegi nii pururumalad ole, et ei taipa, mis ja kuidas. Jaapanlaste harjutuste üldise suunitluse järgi sai selgeks, et neil on käsil kombinatsioonide lihvimine. Raskuse olid nad kinnistunud teatud tasemele ja kogu tähelepanu oli nüüd suunatud esituse puhtusele. Lühidalt öeldes, jaapanlased olid otsustanud minu vastu kasutada minu oma relva puhtust.

Mida ma teadsin jaapanlastes!? Kõike ja mitte midagi. Meie treenerid olid neid mitu aastat uurinud, olid käinud lugematuid kordi Jaapanis, olid tõlkinud jaapanikeelset kirjandust ja välja selgitanud nende treeningumeetodid. Aga jaapanlased jäid meile ikkagi mõistatuslikuks. Jaapani kõige kuulsamad võimlejad Masao Takemoto, Takashi Ono, Sudzuki Nitsukuri, Yukio Endo, Sawao Kato, Akinori Nakayama, Mitsuo Tsukahara. Eidzo Kenmotsu … Neil kõigil olid sarnased naeratused, kummardused, nad kõik kihistasid naerda ja teesklesid lihtsameelsust. Ja õieti keegi ei tundnud nende iseloomu, harjumusi, kalduvusi, huvisid. See kõik oli meie eest seitsme luku taha peidetud. Nad olid kõrgeima klassi virtuoosid, kuid võimlemispõrandal nad

vahel vääratasid, keegi neist ei sarnanenud raudse Sahliniga. Parimad Nõukogude võimlejad on nendega heidelnud ja sageli edukalt.

Mexico OM-il olid jaapanlastel tugevaimad Nakayama ja Kato. Nakayama tundus parem olevat. Mitmevõistluse kava oli tal oivaline, välja arvatud toenghooglemine. Minu eesmärk oli tulla olümpiavõitjaks. Ja mitte lihtsalt võitjaks, vaid absoluutseks. See on kõige lugupeetavani tiitel võimlemises. Kas ma polnud ülearu enesekindel? Paistab, et mitte. Kõigi objektiivsete näitude järgi polnud minu meisterlikkus Dortmundiga võrreldes tuhmunud. Mis oli tehnikas õnnestunud teha? Olin tugevdanud ja uuendanud kombinatsioone vabaharjutuses, toenghooglemises ja kangil.

Minu harjutused vastasid rahvusvahelisele tasemele. Nii et sisuliselt jäi kõik tahtejõu, närvide ja meelekindluse otsustada. Aga sellega oli mul kõik korras.

Olin võiduks häälestatud.

TAKTIKA JA «STRATEEGIA»

Meeskonnaga olid lood keerulisemad. Olümpia-aasta kevadel, pärast üleliidulisi meistrivõistlusi Leningradis, hakkasid kõik rääkima, et lõpuks ometi on meil niisugune koondis, kes on võimeline jaapanlastega edukalt konkureerima. Seda mõtet õhutas oma intervjuus visalt vanemtreener Valentin Muratov, sellest kirjutasid lehemehed, seda kinnitasid meie võimlemisjuhid.

Neil arvamustel oli ka alust. 1968. aastaks olid esile kerkinud noored Viktor Klimenko, Valeri Iljinõhh ja Vladimir Sosin. Aga tipus olid kogenud Diomidov, Lissitski, Karasjov ja mina. Olümpiakandidaate just kuhjaga ei olnud, see-eest millised kotkad!

Leningradis need seitse liidrit lausa hiilgasid. Hinded 9,7, 9,8 ja koguni 9,9 kroonisid meie tööd. Meenutan praegu neid võistlusi ja lihtsalt imestan, kui hästi poisid esinesid hingestatult, raevukalt, kenasti. Tookord näis mulle, et meesvõimlemise õitseaeg on tõesti käes. Pealtvaatajad juubeldasid ja me kõik olime selle üle uhked.

Asja tuum aga seisnes selles, et meistrivõistlustel otsustati teha «teravmeelne psühholoogiline käik». Et jaapanlasi petta, õigemini mitte petta, vaid ehmatada. Seepärast siis tulidki nagu küllusesarvest kõrged hinded. Muide, tõsteti ainult nende meeste hindeid, kes koondisse kandideerisid.

Ka Gorkis, NSV Liidu karikavõistlustel, kus ma ei osalenud, oli pilt samasugune. See psühholoogiline käik ei olnudki uudisasi. Seda oli kasutatud juba Tokio OM-i eel üleliidulistel meistrivõistlustel. Kuid teravmeelne riugas ei õigustanud ennast. Ka jaapanlased olid seda varem kasutanud. Lööd näiteks ajalehe lahti ja loed Jaapani meistrivõistluste tulemusi. Võimlejatel on mitmevõistluses säärased hinded, et võta kätte ja loobu MM-võistlustest seal poleks niikuinii lööki. Pettus läks läbi üks kord, teine, kuid siis me enam tulemustele tähelepanu ei pööranud. Teatavasti on tähtis, mitte hinne, vaid meisterlikkuse visuaalne võrdlemine. Nagu me Mexicos veendusime, ei liigutanud meie imetlusväärsed kogusummad üldse kohtunikke. Nad tahtsid kaupa oma silmaga näha.

Aga meie ei arvestanud muutunud situatsiooni ja olime rahumeeli «strateegia» poolt. Kahjuks tegi see meile kõvasti kahju. Eriti noortele, kes olid OM-i debütandid. Poisid olid uhked kõrgete hinnete üle, samal ajal ka ähmi täis ega teadnud, millist tulemust võis tegelikult arvestada. Kuidas oma jõudu jaotada?

Nii kujuneski välja, et üleliidulised meistrid üksikaladel, kellel olid olnud kõrged, isegi maksimaalsed hinded, ei pääsenud Mexicos finaali, ja kui pääsesidki, siis ei suutnud välismaa sportlastele konkurentsi pakkuda. Oma jõu ja võimete orientiir läks kaotsi just olümpia-aastal. Hiljem mõisteti eksperimendid hukka.

Kuid ma kiirustasin ette.

Siiski saime ka meeskonna kokku. Kõigil olid rasked kombinatsioonid, hea klass ja võiduiha. Ent meeskonnas oli valmimas mädapaise, mida keegi veel ei märganud. See sai kasvamiseks ja arenemiseks toitu ebatervetest suhetest, mis koondises tekkinud.

Valentin Muratov oli silmapaistev võimleja. Ta oli juba tegevspordist loobunud, kui mina alustasin, kuid mul õnnestus teda kinolinal näha. Muratov oli kõige elegantsem võimleja, temast läkski moodi liigutuste «elegantne kalligraafia». Ta oli tahtejõuline, energiline, oma ala võrratu tundja ja alates 1961. aastast hakkas ta koondist juhtima. Ta teadis ja oskas palju, ta õppis inimesi juhtima ja tema autoriteet kasvas aastast aastasse.

Pärast hävitavat lüüasaamist Tokio OM-il, kus vaid Boriss Sahlinil õnnestus kangil kuldmedal saada, oli minu absoluutseks maailmameistriks tulek Dortmundis lausa välk selgest taevast. Kas võis siis arvata, et debütant Voronin suudab mitmevõistluses võita?

Panin tähele, kuidas Muratov hakkas üha sagedamini väitma, et minu võit olnud planeeritud. Arusaadav, et murrang meie võimlemises toimus mitte ainult ühe inimese tahtel, vaid see oli tingitud objektiivsest paratamatusest. 1964. aasta detsembris nägid kõik uut kvaliteedihüpet, noorte ilmumist, kellel suunalt uus kava. Ja Voronini ning Diomidovi edu Dortmundis oli põlvkondade vahetuse, sisuliste muudatuste tulemus. Ent Muratov hakkas vähehaaval rõhutama, et edu saavutati tänu õigele taktikale ja oskuslikule juhtimisele.

Kui koondis oli enam-vähem kindel, hakkas Muratov kruvisid kinni keerama, taotledes, et kõik vastuvaidlematult tema sõna kuulaksid. Töö inimestega eks see ole kõigile teada nõuab suurt taktitunnet. Kui inimene hakkab ennast teistele vastandama, siis osutub ta peagi isoleerituks. Muratov oli küllaltki kaua meie võimlemise tüürimees ja uskus oma ilmeksimatusse. Jah, distsipliini on vaja, karmust on vaja, ka tuleb distsipliinirikkujaid karistada. Ent mulle tundub, et Muratov läks liiale, solvas poisse asjatult.

Ühest küljest oli Muratov lõbus, tark, meeldiv ja sõbralik inimene, võrratu organisaator, julge ja suurte teadmistega treener. Teisest küljest võis Muratov olla ülearu terav. Koondanud võimu enda kätte, ei võtnud ta teisi kuulda ja langetas otsuseid iseseisvalt.

Ei vaidle vastu, Muratovist peeti lugu. Minul olid temaga normaalsed suhted. Kuid ajapikku hakkasid kõik poisid märkama, et vanemtreener peab end vääralt üleval. Tema käitumist oli paha vaadata. Kord vestles sosinal ühega, kord teisega, tegi avalikult peapesu nendele, kes tema juhtnööre ei täitnud. Tookord arvasin, et treeneri tegevus arvustamisele ei kuulu. Alles nüüd mõistan, et Muratov läks lihtsalt ennast täis, keegi talle seda aga ei öelnud. Kahju! Ta tekitas poiste hulgas lahkhelisid.

Eriti tugevad kokkupõrked olid Muratovil Diomidoviga, raske iseloomuga sportlasega, kellele tulnuks isemoodi läheneda.

Ettenägelik võimlemisspetsialist Muratov aimas, et me meeskondlikult niikuinii jaapanlastest jagu ei saa, ometi õhutas versiooni Nõukogude olümpiakoondise enneolematust jõust, üksmeelest ja kõrgest meisterlikkusest. Me kõik olime häälestatud halastamatuks esikohaheitluseks, ent Muratov arvas teisiti. Tema oli otsustanud jaapanlastele pealöögi anda üksikaladel, üritada siin kuldmedaleid.

KONFLIKTID…

Olümpiameeskond koosnes kuuest liikmest ja ühest varumehest. Diomidov, Karasjov ja Sošin treenisid Jevgeni Korolkovi käe all. Klimenko, Lissitski ja Iljinõhh said õpetust Konstantin Karakašjantsilt. Korolkovi peeti nooreks treeneriks, ta oli üles kasvatanud vaid Karasjovi ja mõned meistersportlased. Karakašjants oli silmapaistev treener, kelle õpilaste hulgas mitukümmend meistersportlast ja tuntud võimlejad Valentin Muratov, Viktor Lissitski, Juri Stoida, Viktor Klimenko. Küllap te juba aimate, et Muratov tundis oma treeneri vastu erilist sümpaatiat ja toetas teda igati.

Mexico eel peeti meeskonna liidriteks meid Diomidoviga. Sergei oli maailmameister rööbaspuudel, oli löönud jaapanlasi sõpruskohtumistel ja olümpianädalal, oli võitnud Gorkis NSV Liidu karikavõistlustel.

Üleliidulistel meistrivõistlustel Leningradis olid õnnestunult startinud noored Klimenko ja Iljinõhh, kellel olid varuks rasked harjutused. Nende rünnak oli maruline, näis, et kõik õnnestub neil kerge vaevaga. Mulle meeldisid nende esinemised. Viktor Klimenkot aga pidasin suure tulevikuga võimlejaks. (Järgneb.)

—

Valeri Iljinõhhi suhtes ma tookord prognoose ei teinud. Ta oli närviline, väga keevaline, kaldus upsakusele. Kohutaval kombel kartis võistlusi, enne neid õhetas ja närveeris. Kuid Leningradis oli Iljinõhh löögihoos, ei varem ega hiljem ole ta paremini esinenud.

Ent ka Iljinõhhi ja Klimenko õnnestumist hinnati mõnevõrra valesti. Apellatsioonižüriid juhtiv Muratov andis kohtunike brigaadile teel näpunäiteid. Meie aga olime üsna hämmeldunud, õigemini nördinud, et neile noortele võimlejatele pandi ilmselt ülehindeid (kuigi, nagu ma juba ütlesin, tõsteti kõigi pretendentide hindeid). Ja kukkus niimoodi välja, et nad hakkasid mängima peaaegu et esimest viiulit.

Tookord meile tundus, et Muratov teeb kõik upitamaks liidriteks Karakašjantsi õpilasi. Seda mõtet küttis üles ka Korolkov. Sisuliselt konkureerisid Leningradis ning Gorkis mitte sportlased, vaid rühmitused. Korolkov ja Karakašjants rabelesid ühe kohtuniku juurest teise juurde, hoides teineteisel valvsalt silma peal. Nad olid enesevalitsemise peaaegu kaotanud. Ka meie närveerisime. Piisas vaid sädemest, et puhkeks konflikt. Väliselt paistis kõik rahulik olevat, kõrvalseisjad ei pannud midagi tähele. Kõrged hinded, sensatsioon (tundmatu Iljinõhh saab kangil kuldmedali!), saali vaimustus kõik see oli tähelepanuväärne. Aga ainult sündmustes osalejad teadsid, milliseid närve neil olümplastel tarvis läks.

Ausalt öeldes seisin kõigest sellest veidi eemal. Mind ju tõsteti rõhutatult teiste hulgast esile (ainult saage minust õigesti aru see ei ole kiitlemine, vaid tähtsate sündmuste kaine hindamine. Seepärast püüan olla võimalikult objektiivne).

Enne Mexicosse sõitmist pakkus Muratov välja variandi, kuidas tema aru., mehi koondises paigutada. Teatavasti läheb liider võistlustulle viimasena. Kohtunike hinded, nii on võimlemises traditsiooniks, paranevad järjest ja viimane, kõige tugevam sportlane, saab kõige parema hinde. Muidugi laitmatu esinemise korral. Muratov esitas seesuguse järjekorra, et Korolkov läks marru. Diomidov oli sisuliselt välja lülitatud esikohakonkurentsist mitmevõistluses. Ta oli mõnel alal kolmas neljas number. See oli psühholoogiline torge.

Diomidovi meeleolu langes kohutavalt, ta jäi norgu. Ka mind ei olnud alati viimaseks pandud. Taipasin, et Muratov ei usu ka minusse …

Missugune skandaal treenerite nõukogus puhkes! Korolkov väitis, et Voronin on ainus mees, kes võib ja peab võitma mitmevõistluses, et Diomidovil on kohtunike hulgas suur autoriteet, et tema viimaste aastate võidud lubavad loota väärilist konkurentsi jaapanlastega…

Karakašjants rääkis noorte kasvust, nende huvitavatest kombinatsioonidest, mis vallutavad arbiterid, ja et ainult nemad võivad üksikaladel medaleid saada…

Jagelemine mõjus treenerite ja võistlejate meeleolule. Jah, need olid sünged päevad…

Võib-olla teid huvitab, missugusel seisukohal oli Üleliidulise Võimlemisföderatsiooni esimees G. Baklanov. Vastan: ta toetas Muratovit. Üldse peab Gleb Baklanovist veidi lähemalt rääkima.

Ta juhatas föderatsiooni raskel ajal ja tegi võimlemise arendamiseks palju kasulikku. Ent minu arust tegi Baklanov siiski ka vigu. Ta oli koondises sõjaväelise distsipliini pooldaja.

Ta nõudis treeneritelt niimoodi treeninguid organiseerida, et saaks kronomeetriga kontrollida. Talle ei meeldinud, kui treeningul käratseti, visati nalja või puhati. Talle tundus, et me ei oska õigesti käia, ja ta hakkas meile koguni ise sammumist ning sõdurirühti õpetama. Ta ei hoolinud sportlasele individuaalse lähenemise nõudest. Sellega toetas ta Muratovit ja andis tollele vaba voli.

Mäletan, kord tuli Gleb Baklanov «Dünamo» saali treeningule. Vaatas natuke, siis astus minu juurde ja hakkas seletama, et ma olevat rõngastel valesti pöörelnud. Muide, ma olin juba rohkem kui aasta maailmameister sellel riistal. Siis tegi Baklanov märkuse, et ma ühes elemendis painutan jalga. Seletasin talle leebelt, et vahel ei tule treeningul mõni asi välja ja siis peab elemente või kombinatsioone seni kordama, kuni viimaks midagi koitma hakkab. Mul oli veidi ebamugav. Korolkovil samuti. Aga Baklanovile näis, ei ta oli mind ja treenerit abistanud …

Minu jutt võib tunduda liiga terav, võib-olla isegi lugupidamatu. Saage aru, ma ei taha siluda teravusi. Ma ei räägi ju seda kellegi solvamiseks. Sugugi mitte! Ma vestan aastatest, mis minu meelest olid meie võimlemisele rasked.

Ma räägin selleks, et tulevikus vead enam ei korduks. «Kui palju halba saab avameelsusega kõrvaldada!» on F. Dostojevski öelnud.

Tol ajal upitati üles teooria, mida ma nimetasin «täieliku salastamise teooriaks». Baklanovile ei meeldinud mitte põrmugi, kui meie kohta midagi ajakirjanduses teatati Talle näis, et ajakirjanikud paljastavad oma lugudes meie sportlaste saladusi, mida jaapanlased ei tohi teada. Ta soovitas ajakirjanikele veelgi rohkem salatseda, rääkida sellest, et Nõukogude võimlejad kasutavad uusi treeningumeetodeid, õpivad ennenägematuid elemente. Baklanov arvas, et see kõik ajab meie pearivaalidel hirmu nahka.

Kord kutsus Baklanov ühe korrespondendi enda juurde ja tegi kõva peapesu selle eest, et too oli kirjutanud reportaaži olümpiakoondise treeningust. Ajakirjanik oli lihtsalt jutustanud ühest pingsast ja huvitavast treeningupäevast. Muide, tolles reportaažis oli juttu minust, Diomidovist, Karasjovist ja Sošinist. Baklanov tegi sulemehele etteheiteid, et too oli liiga avameelselt kirjutanud ja jaapanlastele kõik meie kaardid avanud.

Kahju, et Baklanov ja Muratov ajasid meie suhtes nii karmi poliitikat. Ma rõhutan, asi ei ole siin mitte distsipliini tugevdamises (see on vajalik), vaid ebasõbralikes suhetes, mis tekkisid juhtkonnal sportlastega.

… Mõeldes kõrgele missioonile, mis mulle osaks saanud, allutasin oma elu Dortmundist Münchenini ühele eesmärgile võidule olümpiamängudel. Ent kahtlusesäde süttis just sel päeval, mil sain teada, kuidas koondises mehed on paigutatud.

«Tähendab, meid ei peeta kõige tugevamaks? Tähendab, minusse ei usuta?» mõtlesin murelikult. Neil päevil aitas mind tublisti treener. Tema kindel usk, sisendus mitte tähele panna seda äkkrünnakut, tema pikad vestlused tegid head. Sain jälle hingerahu tagasi. Kuid mitte kauaks. Kuni Mexicovõistluste alguseni.

SAATUSLIK JUHUS?

… Säärane oli siis meie koondises olukord XIX olüm-

piamängude künnisel. Keeruline. Ühest küljest, paljud uskusid meie võidusse, minu võidusse; teisest küljest ebaterve õhkkond koondises, treenerite omavaheline nääklemine, vanemtreeneri poliitika, mis, imelik küll, oli suunatud nende vastuolude süvendamisele. Milleks oli seda Muratovile vaja? Või tegi ta seda suure ähmiga? Ei, ei usu. Ta pole selline mees, kes pea kaotaks … Ta lihtsalt oli kaotanud võimu inimeste üle ja üritas nüüd säherduste meetoditega oma autoriteeti taastada.

Mis sellest kõigest välja tuli? Noh, võimlejate tulemused Mexicos on kõigile teada: meeskond kaotas jaapanlastele 4,8-ga (nii suurt lüüasaamist polnud varem olnud), mina sain mitmevõistluses teise koha, Viktor Lissitski ja Valeri Iljinõhh esinesid allpool oma võimeid (14. ja 15. koht), Diomidov ja Klimenko tegid algelisi vigu ega ilmutanud küllaldast vastupidavust, siiski said mõlemad ühe pronksmedali. Minul aga õnnestus üksikaladel koguda 2 kulda, 2 hõbedat ja üks pronksmedal.

Mis mul juhtus?

Pärast kohustuslikku kava olin Sawao Katost 0,3-ga ees. Seejuures olin ainult kahel korral kuuest ankrumees. Kui palju ma väärtaktika tõttu kaotasin? Paar kümnendikku kindlasti…

Jah, ma tegin panuse kohustuslikule kavale. Põhjus oli järgmine. Pärast MM-võistlusi, pärast EM-võistlusi Helsingis, kus ma kuldkarika võitsin, pärast arvukaid välisreise võinuksin kõigele sülitada, lasta sündmustel omapead areneda. Niikuinii iseenda varjust üle ei hüppa. Kukub välja, kuidas kukub. Nii võinuks arutleda. Ja mu südametunnistus olnuks puhas, sest olin ausalt töötanud ja keegi poleks saanud mind laiskuses süüdistada.

Ent mõtted OM-i kuldmedalist polnud mulle kaks aastat rahu andnud. Olümpiavõitja see on midagi iseäralikku, kõige suurem kordaminek spordis. Mõtlesin: kui mul elus on juba nii kõvasti vedanud, siis järelikult tuleb ka spordis seda viimast taotleda. Sellepärast ma ootasingi Mexicot. Kangesti ootasin.

Olümpia kohustuslik kara õnnestus mul hästi. Seda olid kinnitanud arvukad võistlused. Kuskil polnud ainsatki eksimust olnud. Ma viimistlesin ja viimistlesin kombinatsioone ning jõudsin peaaegu virtuoossuseni. Mulle tundus, et olen harjutused kätte õppinud nii, et neid enam puhtamalt ei saagi sooritada. Pärast Leningradis peetud üleliidulisi meistrivõistlusi, kus mul kõik ludinal läks, mõistsin, et võin Mexicos võita. Ma uskusin oma jõusse.

Sawao Kato jäi 0,3-ga maha. Kato, keda peeti kõige puhtamaks Jaapani võimlejaks. Järelikult ma meeldisin kohtunikele, neile meeldis minu stiil.

Arvate, et olin muretu ja enesega rahul? Kaugeltki mitte! Ees oli kõige hirmsam, kõige raskem säilitada saavutatud edumaad. Meeskonnakaaslased olid tagapool, jaapanlased ümbritsesid mind tiheda rõngana. Oli oodata tulist heitlust.

Konkurents meeskondliku esikoha pärast oli sisuliselt juba esimesel päeval lõppenud. Oli jäänud vaid heidelda individuaalmedalite pärast. Pinge oli tohutu, kuid kõik laabus. Kato ei saanud mind kätte ja enne viimast ala olin endiselt liider.

Meie koondisel oli viimaseks alaks toenghooglemine, jaapanlastel vabaharjutused. Ma ei närveerinud. Tundsin ainult viha. Head viha. Alustasin.

Ma polnud veel üldse väsinud, tunnetasin iga lihast. Mulle meeldis hobune, ma valdasin seda ja see polnud mind mitte kunagi alt vedanud. Ent sedapuhku… Jah, näpp takerdus püksisäärde. Tõrge. Hetkeline peatus, kuid see läks mul maksma 0,3 punkti. (Järgneb.)

—

Harjutuse lõpetasin suurepäraselt. Nägin Korolkovi jollis silmi ja sunnitud naeratust. Ta oli keeletu. Pöördus vaatama tablood. Istusin toolile. Silmitsesin samuti tablood. Peas polnud ainsatki mõtet. Ainuüksi ootus.

9,5. Palju ja vähe. Tegin ju vea ja selle eest kärbiti. Võinuks olla ka 9,7 või 9,8.

Hakkasin aegamisi toibuma. Meenus, kuidas näpp püksisäärde oli takerdunud. Kuidas see võis juhtuda? Mitte ei mõista! Varem polnud säärast asja ette tulnud … Mul ei jäänud muud üle, kui Sawao Kato esinemist oodata.

Kato tegi toredasti. Kuid mitte vigadeta. Siin ja sea’ tillukesed vääratused. Mina paneksin 9,7. Võib-olla ma ei ole objektiivne? Hästi, eks pangem siis 9,8. Rohkem küll mitte. See oleks juba liig.

Tablool süttis 9,9. Ma ei uskunud oma silmi. 9,9? Kuidas siis nii? Kus on kohtunike südametunnistus? Mis Valentin Muratovil arus? Oli ju tema just vabaharjutuste arbiter. Tal olnuks õigus kohtunikud kokku võtta ja aru pärida, miks nad vigade eest hinnet ei alandanud. Paraku Muratov seda ei teinud.

Punktid võeti kokku. Kato edestas mind 0,05-ga. See ongi spordis kõige solvavam! Tühine viis sajandikku röövib sinult absoluutse meistri kuldmedali…

Kui ausalt öelda, siis ma ei pidanuks kaotama. Ma ei mõista tänini, kuidas sai sõrm püksisäärde takerduda. Oleksin ma kukkunud, jalgu kõverdunud, elemendi nässu ajanud, siis pidanuksin süüdistama ainult iseennast.

Ent säärane mõttetus! Mille eest mind küll karistati? Mille eest? Tol ööl pidin äärepealt ogaraks minema. Mul olid silmad häbi täis ja eluisu kadunud. Hõbemedali peitsin kohvripõhja (miks ma

seda minema ei visanud, mis mind tagasi hoidis?). Valus tunnistada, kuid ma nutsin öösel patja nagu plika. Närvid ütlesid üles. Siis vajusin sügavasse unne.

Hommikuks olin jälle kaine mõistuse juures. Meeleheitehoog oli möödunud. Olin jälle inimeseks saanud. Kinnitasin: pean ilmtingimata olümpiavõitjaks tulema. Ees seisid üksikalade finaalid.

Kuidas seal läks, seda võimlemissõbrad peaksid teadma. Sain kuldmedalid toenghüpetes ja kangil, hõbeda rõngastel ja rööbaspuudel ning pronksi hobusel.

KES OLI SHS TUGEVAM?

Pärast Mexico OM-i puhkes «Sovetski Spordi» veergudel diskussioon. Vaeti meie meeskonna kaotuse põhjusi. Psühholoogilistest põhjustest ja taktikast ma juba rääkisin. Pean vajalikuks teravdada tähelepanu ka asja tehnilisele küljele.

Oli, kuidas oli, aga Mexico OM sundis treenereid (ja ka sportlasi) tegema treeningusüsteemis olulisi muudatusi.

Niisiis tunneme üsna suurt huvi: a) milliseid uusi suundi esindasid OM-i võitjad ja medalimehed; b) milliseid samme tegid tuntud (ja tundmatud) võimlejad auhindade võitmiseks; c) millise õppetunni said Nõukogude võimlejad.

Et neile küsimustele vastust saada, tuleb eelkõige selgitada, kas «Audiotorio Nationalis» esitati midagi printsipiaalselt uut? Vastan puhtsüdamlikult ei.

OM-i eel käisid ägedad vaidlused, kuidas mõjub «kolme kümnendiku reegel» harjutuste raskusastmele. Selgitan, mis reegel see on.

Üksikalade finaalis hindasid kohtunikud võimlejate meisterlikkust mitte 10-st punktist nagu tavaliselt, vaid 9,7-st. Kohtunikud võisid sellele hindele lisada 0,1 riski, originaalsuse ja väljenduslikkuse eest (seega kokku võimalik 4-0,3).

«0,3 punkti reegel» sundis maailma paremaid võimlejaid oma harjutusi uuesti läbi mõtlema. Nagu võistlused näitasid, olid nad pearõhu asetanud puhtusele, väljenduslikkusele ja originaalsusele. Jaapanlaste kombinatsioonid olid meie omadest mõnevõrra raskemad, kuid mitte see ei andnud neile veel paremust. Nad olid meist ka originaalsemad.

Jaapanlased olid «0,3 punkti reegli» õigesti lahti mõtestanud. Raskuselt olid nende harjutused laitmatud, aga kombinatsioonid torkasid silma just omapäraga, need ei olnud šabloonsed. See kandis head vilja.

Missugused olid meie võimlejate puudused? Vaadelgem finaalvõistluste tulemusi (kasutan päevikumärkmeid, mis juba Mexicos tehtud).

VABAHARJUTUSED. Sel alal olid finaalikuuikus 5 jaapanlast. Valeri Karasjov jäi 5-ndaks.

Vabaharjutusi nimetatakse jaapanlaste monopoliks: siin on nad virtuoosid. Minu meeskonnakaaslaste harjutustes oli küllaga raskeid elemente, kuid vormilt olid need ebahuvitavad. Need olid üles ehitatud tavalise skeemi järgi. Jaapanlased ei olnud nii konservatiivsed. Mõistsime, et oleme siin kõvasti, kuid mitte lootusetult maha jäänud.

TOENGHÜPPED. Tokios sooritas H. Yamashita uue toenghüppe. Tema nimega see ristitigi. Peagi õppisid kõik selle hüppe ära ja keegi ei tahtnud midagi muud leiutada. Mexicos pidid võimlejad oskama kaht hüpet. Selleks ei olnud paljud valmis. Minul kukkusid mõlemad katsed vist päris hästi välja. Esikoht anti mulle. Diomidov oli kolmas. Jaapanlased olid sellel alal kesised.

RÕNGAD. Pärast Albert Azarjani lahkumist läksid loorberid Tokios T. Hayatale ja Mexicos A. Nakayamale. Kahe aasta eest Dortmundis olin rõngastel võitnud mina. Põhimõtteliselt võinuksin ka nüüd esimene olla: Nakayama edumaa oli tühine. Neli jaapanlast ja meie kahekesi, Diomidov oli kuues. Iseloomulik? Jah. Nemad olid kehalise ettevalmistuse poolest meist tugevamad, neil oli rohkem ilusaid raskeid elemente. Uusi leide ei olnud, kuid puhtus oli neil võrratu.

RÖÖBASPUUD. Võitis Nakayama. Veenvalt! Mina sain teise koha, Klimenko kolmanda. Ja ikkagi oli jaapanlaste esinemine huvitavam ja mitmekesisem. Meie omadest oli perspektiivikas kombinatsioon ainuüksi Klimenkol.

KANG. Jagasime Nakayamaga esikohta. Ausalt öeldes ma ei lootnud sellel riistal võita, kuid nähtavasti meeldisin kohtunikele ja finaalis kukkus mul ka kõik ilusasti välja. Nakayama ja teiste jaapanlaste kombinatsioonid rabasid mind. Nad on siin meist kaugele ette läinud.

TOENGHOOGLEMINE. Jaapanlased on hobusel alati hädas olnud. See on neil kõige

mahajäänum ala. Finaali pääses nende hulgast ainult üks Kenmotsu (5. koht). Klimenko jäi kuuendaks, mina kolmandaks. Võitis jugoslaavlane Miroslav Cerer, Tokios oli ta samuti esimene. Midagi uut ta ei näidanud. Diomidov, Lissitski ja Klimenko esitasid mitmeid uusi elemente, kuid selle peale ei reageeritud. Tõsi, nad polnud kindlad. Nii nagu minagi. Üldiselt aga võime hobusel kaugele jõuda.

…Nõndaks. Enne Mexicot arvasime, et oleme jaapanlastele järele jõudnud, aga tegelikkus näitas, et olime neist hoopis maha jäänud. Olime tugevamad kui kunagi varem, aga jaapanlased olid veel tugevamad. Midagi tuleb põhjalikult ümber korraldada.

Appendix: A Video about Valentin Muratov and Sofia Muratova

[00:00:00]

Speaker 1: Good morning, friends. Let’s start the first exercise.

[music]

Speaker 2: In the family of the senior coach of the national gymnastics team Valentin Muratov, the day begins with morning exercises. The young Muratov also dream of becoming gymnasts: the five-year-old Andryusha and the thirteen-year-old Sergey.

[music]

Speaker 2: [00:00:30]. Merited Master of Sports Sofia Muratova is not a famous champion for her sons, but just a mother. It’s hard for them to imagine that not so long ago she was such a girl with braids – Sonya Poduzdova, one of the best gymnasts of the country.

[music]

[applause]

Speaker 2: [00:01:00] From this modest cup the collection of sports trophies for the Muratov family began.

[music]

Speaker 2: But even today, champions do not leave the big sport. Following Valentin, Sofia also switched to coaching. One of Muratov’s students is Olga Kharlova. During the last World Championships in Dortmund, she defended the honor of the national team of the Soviet Union.

[music]

[00:01:30]

[music]

Speaker 2: Determination, hard work – these qualities have always distinguished Sofia Muratova. Now she’s teaching these qualities young people.

[music]

Speaker 2: One of Kharlova’s favorite apparatus is the uneven bars. [00:02:00] Olya seemed to inherit her love for them from her coach.

[music]

Speaker 2: The young gymnast is not doing well yet, which means that she is still in search of new things, new trainings. Yes, the Muratov family is loyal to big sports. They pass on their traditions to a new generation of [00:02:30] gymnasts.

[00:00:00]

Диктор 1: Доброе утро, товарищи. Начали первое упражнение.

[музыка]

Диктор 2: В семье старшего тренера сборной команды страны по гимнастике Валентина Муратова день начинается с утренней зарядки. Мечтают стать гимнастами и Муратовы-младшие: пятилетний Андрюша и тринадцатилетний Сергей.

[музыка]

Диктор 2: [00:00:30] Заслуженный мастер спорта Софья Муратова для своих сыновей не прославленный чемпион, а просто мама. Им трудно представить, что не так уж давно она была вот такой девушкой с косичками — Соней Подуздовой, одной из сильнейших гимнасток страны.

[музыка]

[аплодисменты]

Диктор 2: [00:01:00] С этого скромного кубка началась коллекция спортивных трофеев семьи Муратовых.

[музыка]

Диктор 2: Но и сегодня чемпионы не покидают большой спорт. Вслед за Валентином перешла на тренерскую работу и Софья. Одна из учениц Муратовой — Ольга Харлова. На последнем чемпионате мира в Дортмунде она защищала честь сборной команды Советского Союза.

[музыка]

[00:01:30]

[музыка]

Диктор 2: Настойчивость, трудолюбие — эти качества всегда отличали Софью Муратову. Теперь она воспитывает их у молодежи.

[музыка]

Диктор 2: Один из любимых снарядов Харловой — брусья. [00:02:00] Любовь к ним Оля как бы унаследовала у своего тренера.

[музыка]

Диктор 2: У юной гимнастки еще не все получается, а это значит, впереди новые поиски, новые тренировки. Да, Муратовы верны большому спорту. Они передают свои традиции новому поколению [00:02:30] гимнастов.