It’s no secret that Marie Provazníková of Czecholoslovakia was one of the first known political defectors at an Olympic Games.

However, what has been lost over the years is the context of her defection, particularly the role that gymnastics played in her desire to seek political asylum.

So, let’s take a closer look at her story, starting with the Sokols in the 1940s.

Note: On August 16, 1948, the Dutch newspaper Het nieuws, like the AP, reported that there were other defectors at the Olympics.

The Sokol Movement’s Democratic Leaning | Political Upheaval in 1948 | Provazníková’s Defection | Czechoslovak Coverage | More about the Sokols

The Sokol Movement’s Democratic Leanings

To understand Provazníková’s defection, we have to understand the Sokol organizations and their ideological leanings in the early twentieth century.

Basic knowledge, part 1: Prior to World War I, the Czech and Slovak people were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Basic knowledge, part 2: The Sokols are gymnastics societies that served as cultural organizations in Czechoslovakia, in other Slavic countries, and in the Slavic diaspora at large. (For more on the history of the Sokol movement, jump to the bottom of the page.)

Basic knowledge, part 3: In 1918, the country of Czechoslovakia was formed, and its 1920 constitution established a parliamentary democracy.

How this relates to gymnastics: In the 1940s, the Czechoslovak Sokol movement was seen as an essential part of the democratic movement.

Don’t believe me?

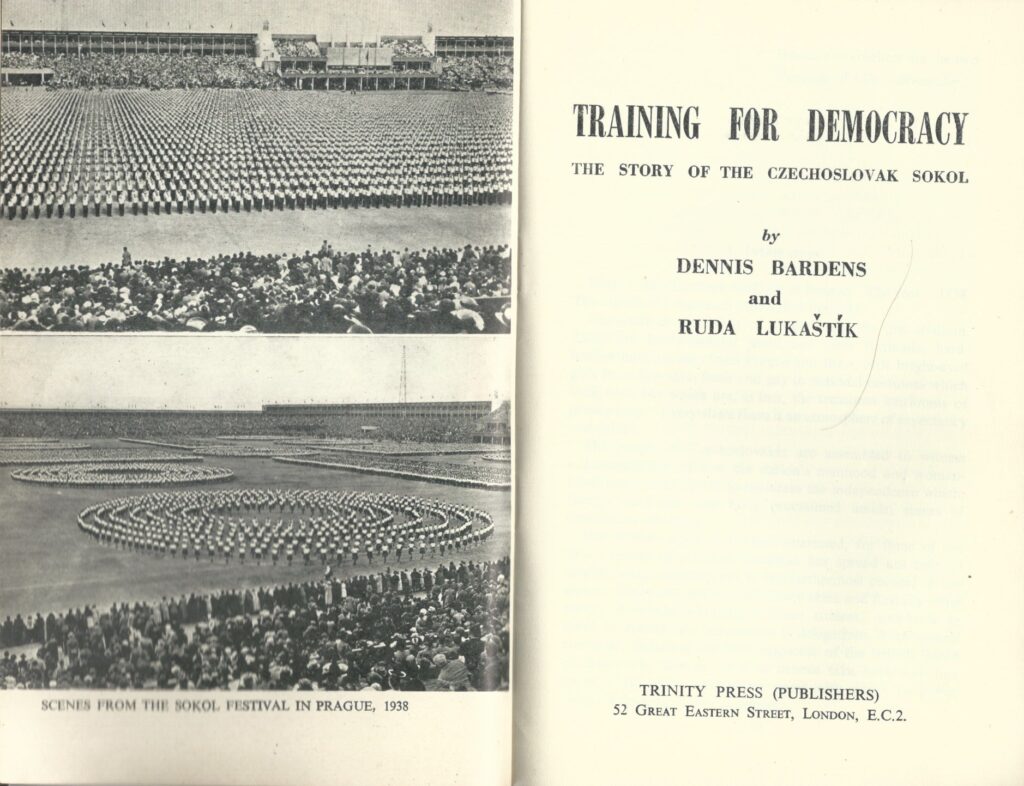

This was a book title: Training for Democracy: The Story of the Czechoslovak Sokol (1945).

Diving Deeper into the Sokol ideology

The movement was founded by Miroslav Tyrš and his father-in-law, Jindřich Fügner, in 1862, and it was a way of trying to reestablish a Czech identity even as the Austrian empire tried to suppress it.

Here’s an excerpt from a book written in 1948:

Through specialized studies in the departments of philosophy, art, religion, literature, natural sciences, mathematics and astronomy, and extensive travel in European countries, Dr. Tyrš widened his mental horizon and deepened his philosophical outlook. He was thus in a position to envisage and treat the problems of his nation from the higher vantage point of humanity and world history and, in doing so, came to the conclusion that neither the rebirth of a nation’s language and culture nor its political and economic revival are sufficient to guarantee a nation’s future. A nation so weakened in its physical substance and in its moral and spiritual fibre as was the Czech nation after the White Mountain must renew that physical substance, restore health and strength, re-form its character and regain its national pride and self-confidence so that it may enter the family of nations on a basis of real and acknowledged equality.

The problem was how best to achieve this end. Tyrš (and this was his great merit) found a means as simple as it was effective — physical training. From his studies of classical Greece, he made the significant discovery that among the Greeks physical training and the cultivation of the civic virtues went hand in hand. In spite of the Greeks being, like the Czechs, a small nation, physical training made them able to withstand the attacks of physically more powerful peoples.

Věnceslav Havlíček, The Sokol Festival, 1948

The following quotes flesh out the Sokol ideals of the 1940s a bit more.

Disciplined with Freedom of Thought

By what means can a vast body of people conform to discipline without becoming standardised in thought? Who devised a scheme so elastic and comprehensive that young and old, robust and delicate, could all, according to their individual needs, receive the benefits of physical training? Such questions, to which Czechoslovakia found the solution, have not only perplexed the Western democracies in the past, but will concern them in the future.

Training for Democracy by Dennis Bardens and Ruda Lušatík, 1945

Peace among the Slavs

With the Sokol idea and organization among the Slav nations, there was linked the awakening of a Slav consciousness, democratic in spirit and serving as an instrument of common humanity. In this sense, the Sokol wielded its influence to dissolve prejudices and to settle disputes among the Slav nations as, for instance, between the Poles and Russians, Serbs and Bulgarians, Croats and Serbs. Meeting on Sokol ground, they got to know each other, learned to discuss matters amicably and work together. Such intercourse led to mutual understanding where there was suspicion, to an awakened interest where there was indifference, and to reconciliation where, formerly, there was hostility, and every such drawing closer of nations and communities is a direct gain for humanity.

Věnceslav Havlíček, The Sokol Festival, 1948

Honest Democracy

The Sokol wishes the Slet to serve their own nation and the world as an example of how it is possible to carry out a great community task without dictatorship or force, without corruption or craft, on a purely voluntary basis and on the simple strong foundation of honest democracy and love of one’s fellow-beings. Herein lies the universal significance of the All-Sokol Rallies.

Věnceslav Havlíček, The Sokol Festival, 1948

A Drastic Change in 1948

The political situation of Czechoslovakia changed in 1948, prior to the Sokol Festival.

A Quick Summary

- In 1920, the Czechoslovak Constitution was ratified, establishing a parliamentary democracy in the country.

- In 1935, Edvard Beneš, a socialist, was elected as President by the Czechoslovak Parliament.

- During World War II, Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, and Beneš led his country’s government-in-exile from London.

- In 1945, Beneš returned to Czechoslovakia and re-established the government on native soil.

- Though his return was celebrated, Beneš quickly made some contentious decisions, which are called the “Beneš decrees.”

- Starting in 1945, he stripped citizenship of millions of Germans and thousands of Hungarians unless they could prove their wartime loyalty to the Czechoslovak state.

- Their property was confiscated without compensation, and thousands were killed during their forced expulsion.

- In February of 1948, the communist prime minister, Klement Gottwald, demanded that Beneš accept a communist-dominated cabinet. (Some have called this as a coup d’état.)

- In May of 1948, a rigged election took place, which ensured a communist majority.

- Beneš refused to sign the new constitution and resigned on June 7, 1948.

- During the Sokol Festival in July, many participants held onto their democratic ideals and defied the country’s communist leadership by cheering for the symbol of Czechoslovakia’s defunct democracy: “Long live Edvard Beneš!”

- As a result, the police got involved, and the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia investigated the Sokol organization, ousting several key members.

If that was enough history for you, jump to the next section about Provazníková’s defection. Otherwise, here’s some more history…

Timeline: Diving Deeper into the Sokols in 1948

March 1948: Czechoslovak-Americans were reportedly under suspicion leading up to the 11th Sokol Festival.

The reiteration that Americans are engaged in spying on Czechoslovakia and in conspiracies against her and her allies is running into conflict with the strong effort being made here to turn the eleventh Sokol games into a major propaganda effort of the Communist-dominated regime.

Before the recent political events here several thousand Americans of Czech origin were expected to visit Czechoslovakia for the games this year. There are Sokol organizations in the United States.

A large number of Slovaks also were registered to come to the Sokol games. However, every Czechoslovak who has intimate connections with the United States is now more or less under suspicion. There has been so much propaganda on the subject of an alleged plot against Czechoslovakia by the Western powers, notably by the United States, that relatives and friends who come to visit Czechoslovakia cannot avoid casting suspicion on them.

NYTimes, March 3, 1948

June 1948: In the rehearsals leading up to the Sokol Festival, a group cheered for President Edvard Beneš. Many groups were refusing to participate.

At Brenn (Brno), according to a report, the Sokol group began to shout, “Long live President Benes!”

More serious it is said, is the possible eventual effect on the adult games, the chief attraction of the Sokol exhibitions. Many groups have refused to train. Information reaching Prague indicated that groups in various localities ceased training shortly after the February events and have refused to continue at all or have continued spasmodically with increasing difficulties.

NYTimes, June 20, 1948

July 1948: President Beneš was cheered at the Sokol Festival.

Former President Eduard Benes was cheered today by 80,000 persons marching through Prague in the Sokol Congress parade. There were no cheers for his communist successor, President Klement Gottwald.

[…]

“We have no true republic without T. G. Masaryk and Benes,” the marchers changed as they swung through the streets in the rain.

M. Masaryk was Czechoslovakia’s first president. Soon after the Communist coup in February, his son, Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk plunged to his death. M. Benes quit recently without signing the new Communist Constitution.

Sokol members cried, “Long Live Brother Benes.”

NYTimes, July 7, 1948

July 1948: Shortly thereafter, the police became involved.

The Government ordered an investigation of the Sokol Congress today as Czechs again staged popular demonstrations for Presidnet Eduard Benes.

[…]

When a small group sang patriotic songs in front of the Communist party headquarters the police appeared suddenly, arrested a half-dozen persons and put them in a police van.

Early today police broke up groups that traveled about the city cheering M. Benes, singing the national anthem and even paying apparent homage to the late Woodrow Wilson.

NYTimes, July 8, 1948

July 1948: Czechoslovak officials promised a purge.

Officials of the Sokol said last night they were sorry that its July 6 parade has been used as a kind of political demonstration. They promised a purge.

NYTimes, July 17, 1948

July 1948: The communist government took over the Sokol organizations.

The Government decided today to set up a special committee to supervise sports and gymnastics.

[…]

Today’s announcement apparently meant that the Communists would run the Sokol organization.

NYTimes, July 31, 1948

August 1948: While the Olympics were happening, Sokol officials were ousted.

The Czechoslovak radio said tonight Frantisek Konvalinka, chairman of the Sokol of Livinow district of northern Bohemia, had been expelled from the organization.

NYTimes, August 4, 1948

August 1948: The Sokol organization underwent a re-organization of sorts.

The Sokol system is to be completely reorganized so that it may become “a progressive society of the whole nation imbued with the ideals of a people’s democracy,” according to an official statement by the general secretariat of the Central Action Committee published to-day.

This complete metamorphosis of what was formerly a voluntary organization into what appears to be a compulsory one is a sequel to the anti-Government demonstrations during the Sokol festival in June and July. According to the Central Action Committee’s statement the number of demonstrators was “very small.” Nevertheless, already the whole Sokol directorate for Moravia has been dismissed for taking part as well as an unknown but large number of other local and headquarters officials

The Times of London, August 23, 1948

What does any of this have to do with Provazníková’s defection?

In 1946, after the conclusion of World War II, Marie Provazníková became the president of the FIG’s Women’s Technical Committee. (Taylor of Great Britain became vice president, and Trouette of France became the secretary).

Two years later, Provazníková resigned from that position and defected from Czechoslovakia.

And it all had to do with the Sokol festival in 1948.

🤔 Remember how the Sokols had democratic roots?

🤔 And remember how the Sokolists defied the communist leadership by cheering for their former president during the Sokol festival?

🤔 And remember how the communist government was investigating the Sokol leaders who cheered for Beneš?

Well, Provazníková was one of those who cheered for Beneš during the 1948 Sokol Festival.

Here’s what the New York Times printed:

One of Czechoslovakia’s most popular women, Mrs. Marie Provaznikova, 57-year-old leader of the Czechoslovak women’s contingent at the Olympic games, declared today that she would not return home but would seek asylum in the United States.

Although the Czechoslovak Embassy said she was remaining abroad with the approval of the Communist-led Government in Prague, Mrs. Provaznikova declared: “I am a political refugee and proud of it. It is a strange feeling to leave my country in which I have worked all my life, but it is the only way to be a free agent.”

Mrs. Provaznikova said that she was afraid that if she returned home she would be obliged to sanction the purge in the Sokol [national fitness organization] in which she was teh leader of a half million women.

Last month at a Sokol rally in Prague in which she commanded a body of 28,000 women gymnasts a demonstration occurred for former President Eduard Benes and Mrs. Provaznikova cheered because of her known sympathies for Mr. Benes.

“It was a spontaneous expression and it was anti-Gottwald,” said Mrs. Provaznikova, referring to Dr. Benes’ Communist successor, President Klement Gottwald.

Children shouted “Long Live Benes” and women cried “You cannot dictate whom we shall love.”

Afterward Mrs. Provaznikova was visited by policemen but because she was not in the stadium at the time she was able to disclaim responsibility for the demonstration. She was warned, she said, that she would be held personally responsible for a repetition of the demonstration.

In spite of that experience she was allowed to come to London for the Olympic Games, she said, because she was president of the International Gymnastic Federation. She resigned that post at the end of the London games.

Yesterday Mrs. Provaznikova went to the Czechoslovak Embassy to apply for an extension of her passport to allow her to accept an invitation to lecture on gymnastics and Sokol methods in the United States. Friends said she informed the embassy that whether the extension was granted or not she did not intend to return to Prague.

Today an Embassy spokesman, praising Mrs. Provaznikova as “a fine instructor” and an “outstanding athlete,” declared that she was going to the United States “with the blessing and the knowledge of Prague.”

Josef Josten, former Czechoslovak Foreign Office official, at whose home Mrs. Provaznikova was interviewed, said she had received an invitation from an old friend, Mrs. Margaret Brown, president of Panzer College of Physical Education, East Orange, N. J., to lecture there. She will leave London as soon as she can obtain a United States visa, Mr. Josten said.

Two more Czech refugees arrived here tonight as stowaways in the cramped tail of a Czechoslovak airliner, according to The Daily Mail. Both are under 21 and were ground engineers at Prague airport who paid an official to lock them in the compartment where they were discovered only by chance.

NYTimes, August 19, 1948

The details of her defection vary from account to account. For example, an article from The Times of London indicated that Provazníková had been dismissed — rather than warned — before her departure for the Olympic Games.

Regardless, both articles made it clear how Provazníková felt about the communist government in Czechoslovakia:

Among the [dismissed Sokol officials] is Mrs. Marie Provaznikova, the chief woman Sokolist, who was dismissed during the festival because she called for cheers for “Our brother President” instead of for President Gottwald by name. The children she was exercising responded by shouting, “Hurrah for President Beneš.” In spite of her dismissal Mrs. Provaznikova was allowed to lead the Czech women’s Olympic gymnasts, who declared they would not go to England under any other leader. The fact that Mrs. Provaznikova remained in England when the team returned and has announced that she is “a political refugee and proud of it” has not so far been published here.

The Times, August 23, 1948

How was Provazníková’s defection communicated in Czechoslovakia?

There was quite the political spin. Here’s what Ľud, a Slovak-language publication, printed:

Provazníková, a Gymnastics Instructor in the USA

The head of the Olympic women’s gymnastics team, Mária Provazníková, canceled her return to Prague. According to a report from the Czechoslovak Embassy in London, Provazníková is going to the USA for a year as a gym instructor. Provazníková leaves with the permission of the Czechoslovak authorities. On this occasion, a representative of the Czechoslovak Embassy reported to a Reuters correspondent that Sister Provazníková played the main role in the victory of Czechoslovak women at the XIV. Olympic Games in London. Mária Provazníková is truly one of the best instructors in gymnastics to which she has dedicated her entire life. Her departure to the USA, where she will be a gymnastics instructor, is certainly the best business card for Czechoslovak gymnastics abroad.

Provazníková ako inštruktorka telocviku do USA

Vedúca olympského telocvičného družstva československých žien Mária Provazníkové odvolal svoj návrat do Prahy. Podľa zprávy československého veľvyslanectva v Londýne, odchádza Provazníková na rok do USA ako inštruktorka telocviku. Provazníková odchádza so svolením československých úradov. Pri tejto príležitosti vyhlásil zástupca československého veľvyslanectva Reuterovmu spravodajcovi, že sestra Provazníková má hlavný podiel na víťazstve československých žien na XIV. olympských hrách v Londýne. Mária Provazníková patrí skutočne medzi najlepšie inštruktorky telocviku, ktorému zasvätila celý svoj život. Jej odchod do USA, kde bude inštruktorkou telocviku, je iste najlepšou vizitkou o dobrom zvuku československej gymnastiky v zahraničí.

Ľud, August 20, 1948

By no means was this a year-long stint.

Provazníková died in Schenectady, New York in 1991.

Into the Weeds: More on the Sokol Movement

In “Sport in the Czech and Slovak Republics and the Former Czechoslovakia and the Challenge of Its Historiography,” Stefan Zwicker includes this short history of the Sokol movement:

Undoubtedly, the Sokol (“Falcon”) movement, founded by Miroslav Tyrš in 1862 shortly after Austria became a constitutional monarchy, was the most politically important movement in European sport. Tyrš and his closest comrade Jindřich Fügner, both of ethnic German origin and “converts” to the Czech nation, created the movement on a German model to symbolize Slavonic pluck and Czech self-consciousness. It had much in common with Friedrich Ludwig Jahn’s Turnbewegung, not only in its emphasis on physical training and paramilitary ethos but also in its glorification of the nation’s collective past. In this sense, Frank Boldt was correct in stating that Sokol was simultaneously anti-German and German through and through. The sokolovny (gymnastic halls) were decorated with busts and portraits of Hussite military leaders, and bodily training was understood not as an end in itself or as something that benefited the individual athlete but rather (under the slogan “Every Czech a Sokol!”) as an exercise in the service of the country and nation. Just like the German Turner, Miroslav Tyrš offered “his” organization up fully to the cause of national emancipation but nevertheless kept his distance from political parties for fear of a possible ban from the Austrian authorities—a far-sighted decision that helped Sokol to become the largest Czech association and personification of Czech nationalism from the 1880s onwards. Sokol instructors and Czech Sokol as such inspired other countries to found brother organizations, especially among the all-Slavic nations (i.e., Poles, Bulgarians, Croatians, and Slovenes) and played a significant role in the formation of physical education in Russia. Sokol units also began to spring up among the Czech minority in Vienna and emigrants in Western Europe and the United States, where the first Sokol unit was founded as early as 1865.

Despite splits or the foundation of new politically or religiously motivated organizations—in 1897 Dìlnická Tìlovýchovná Jednota (DTJ, “Workers’ Gymnastic Organization”) separated from Sokol, and in 1909 already existing Czech Catholic gymnastic clubs came together under the name Orel (“Eagle”)—Sokol remained by far the leading Czech gymnastic organization. It held meetings at six-yearly intervals called slety (“flying together”), and even before 1914 these developed into mass gatherings. Sokol functionaries played a leading role in the 1918 coup d’état in Prague that led to the foundation of Czechoslovakia and were subsequently entrusted with high office in the new state apparatus. Not surprisingly, Sokol was one of the most important organizations in the First Republic (from 1918 to 1938). During the Nazi “Protectorate” it was disbanded in April of 1941, and in October of the same year many of its members, some of whom belonged to resistance groups, were arrested in Gestapo mass raids and deported to concentration camps. Under Communist rule, Sokol, like all other sporting organizations, was forced to toe the party line, Spartakiads celebrating Socialism replacing its slety. In the wake of 1989 Sokol had property restituted to it, and it is very popular as a leisure sport activity, even if it has lost the importance it held in society before the Second World War.

Parallel to Sokol, the Czech Olympic movement had a particularly national orientation too in its early years before 1914. Just as Czech politicians demanded autonomy within the Habsburg monarchy (e.g., in relation to Bohemian state law), Olympic athletes were able to project themselves to international publics as representatives of a nation in its own right. Thanks both to the diplomatic skills of sports functionary Jiří Guth-Jarkovský, one of the founding members of the International Olympic Committee, and to certain rules that stipulated from 1914 that National Olympic Committees could be founded by members of a nation without their own state, Czech delegations—much to the chagrin of the Austrian authorities—were allowed to represent an autonomous nation at the Olympic games. In the Communist era, however, the Czechoslovak Olympic Committee had to follow directions from party and state, most notably when it was forced to join the boycott of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Note #1: Even before the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, Czech gymnasts were competing in international gymnastics competitions. I wrote about the 1889 French Federal Festival here.

Note #2: As I’ve said many times on this site, history is a matter of perspective. Writing in 2011, Zwicker can see both the German and anti-German tendencies in the Sokol movement. However, that wasn’t the case in 1948. Sokol historians in the ’40s were actively trying to distance themselves from the Germans:

True to the Greek ideal of kalokagathia [i.e. the harmonious combination of bodily, moral, and spiritual virtues], Tyrš did not allow himself to be drawn by the German ‘Turner’ ideal of physical strength for its own sake, but rather did he seek to harmonize strength with beauty and nobility. In this endeavor, Sokol physical training places special emphasis on beauty, as is apparent from the whole set-up of the Sokol celebrations.

Věnceslav Havlíček, The Sokol Festival, 1948

Reminder: The Germans invaded occupied Czechoslovakia during World War II. Understandably, the Czechoslovaks in 1948 felt animosity towards Germany (as did much of the world at the time).

That said, as we discussed above, the anti-German sentiment in Czechoslovakia had some dire consequences. There were many ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia at the time, and unless they could show their loyalty to the Czechoslovak state, they were stripped of citizenship, their property was confiscated without compensation, and thousands were killed during their expulsion.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

Up next: We’ll take a look at what happened during the 1948 Olympics before Provazníková’s resignation from the FIG and defection to the United States.

2 replies on “1948: The Political Defection of Marie Provazníková, President of the FIG WTC”

What an incredibly comprehensive job you have done. Provaznikova was my grandmother. In April, under the aegis of SVU, NY (Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences) I created a zoom 2 hour collage of her life. We are in the final process of editing Part I. As a prequel, Harry Blutstein, author of Cold War Olympics also talked about her and Olga Fikotova in February. Here is the link to Harry’s talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1PpEvRufpc&list=PLCxVJ0QhOLvIeFr3va6F11CHW2eokTXju

Congratulations! You have done a wonderful job

Děkuji! I look forward to seeing more videos about your grandmother!