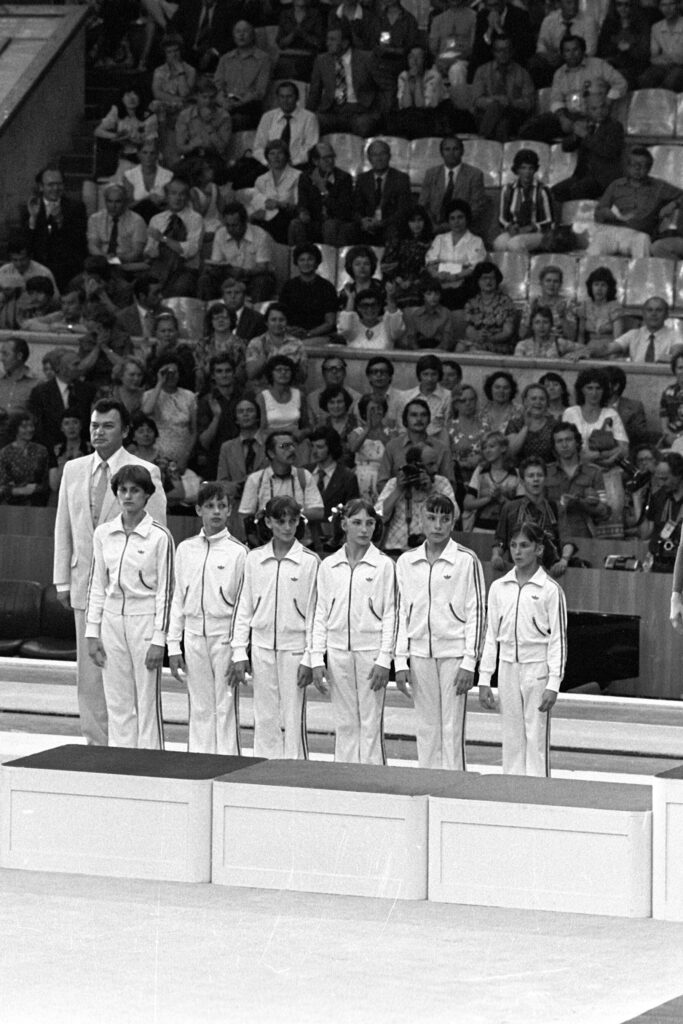

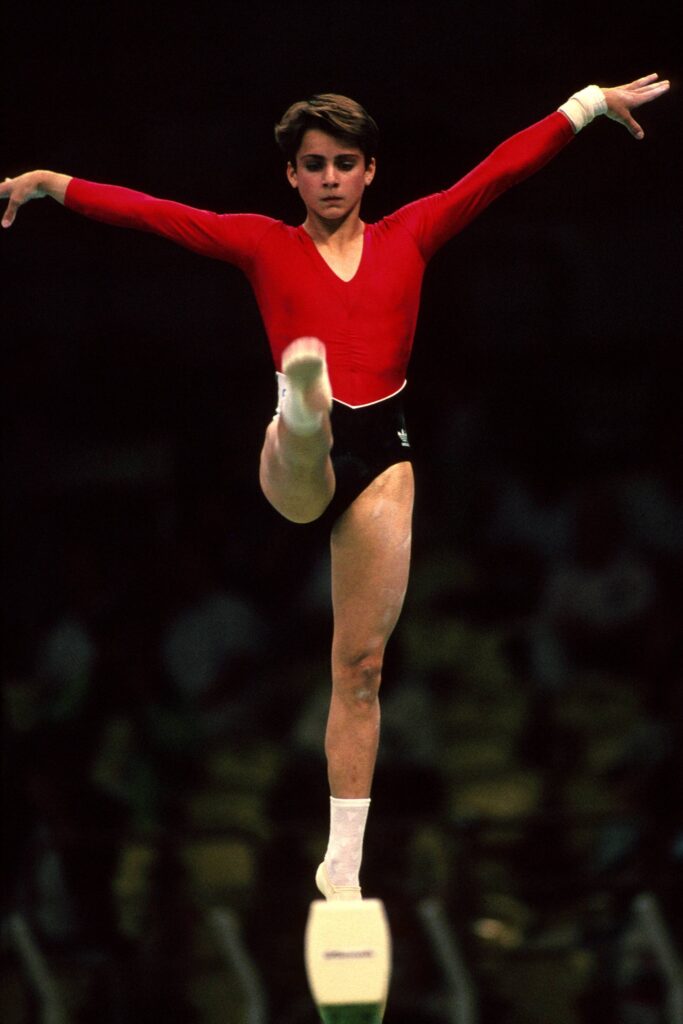

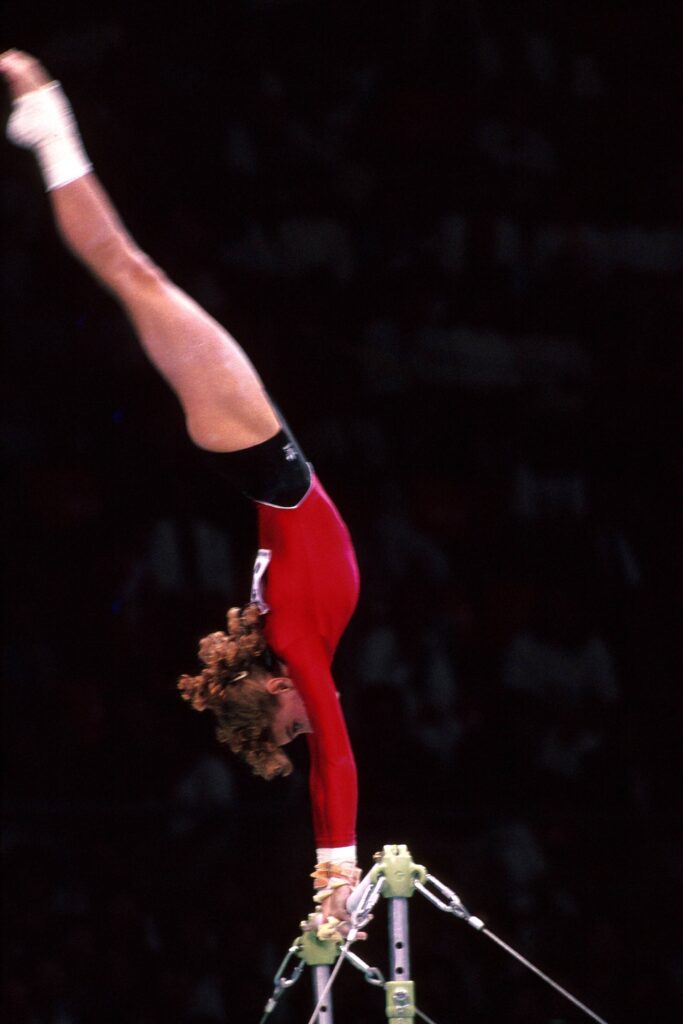

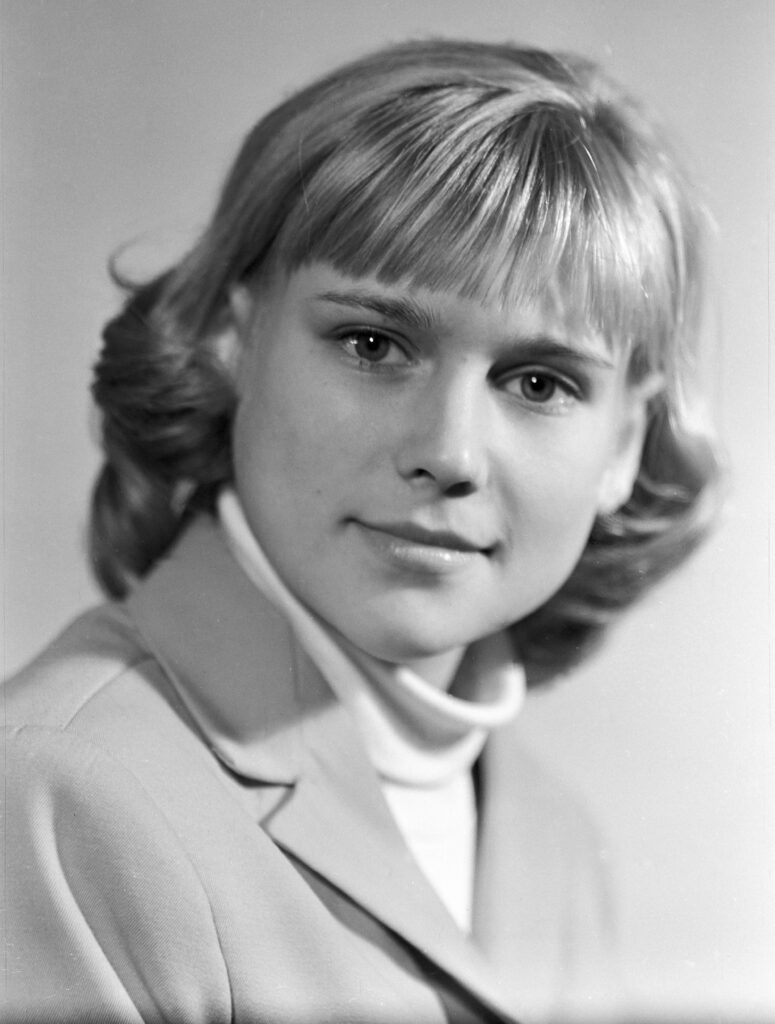

In October 2002, more than two decades after Romania’s women’s gymnastics team won gold in Fort Worth, Rodica Dunca broke a long silence. Speaking to Pro Sport, the former international gymnast described daily life inside the Deva training camp not as a center of excellence, but as a place of hunger, surveillance, fear, and physical coercion. Her testimony names teammates whose faces became global symbols of grace—Nadia Comăneci, Melitta Rühn, Emilia Eberle (Trudi Kollar), Dumitrița Turner, Teodora Ungureanu—and places their medals alongside scenes of beatings, escapes intercepted by the Securitate, and bodies pushed beyond collapse. What Dunca recounts is not a single shocking incident, but a system: one in which control over food, water, movement, pain, and obedience defined her adolescence.

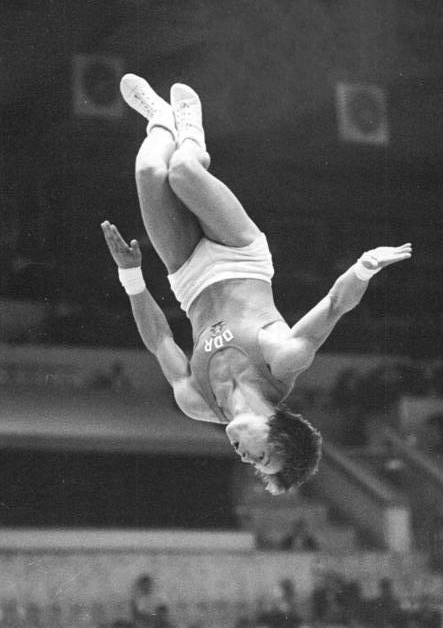

Like Eberhard Gienger, Dunca recalls being given an obscene number of pills and injections; unlike Gienger—who admitted to returning many of them to the pharmacy—she was compelled to take everything she was given. Dunca does not identify the substances involved, making it impossible to determine whether any appeared on the IOC’s banned list. She was competing, moreover, in an era when the FIG did not conduct systematic testing, and when the reliability of the drug controls at the 1980 Olympics remains questionable at best. Even had prohibited substances been involved, a positive test would have been unlikely.

Yet the absence of a positive test is not the absence of a problem. Dunca’s account instead directs attention to the medical regime under which Romanian gymnasts trained and competed. The forced ingestion of dozens of unidentified tablets each day, the routine administration of injections associated with prolonged amenorrhea, and the later emergence of drug dependence—all point to a system of non-therapeutic, coercive medical management that regulated young athletes’ bodies for performance, not health.

Set against official narratives of discipline, sacrifice, and triumph—most famously associated with Béla Károlyi—Dunca’s interview exposes the cost hidden behind the perfect smiles and historic scores. It is a reminder that Romania’s golden era in women’s gymnastics was built not only on innovation and talent, but also on practices that blurred the line between training and punishment, medicine and control, excellence and abuse.

Below, you’ll find a translation of ProSport‘s interview with Dunca from October 26, 2002.