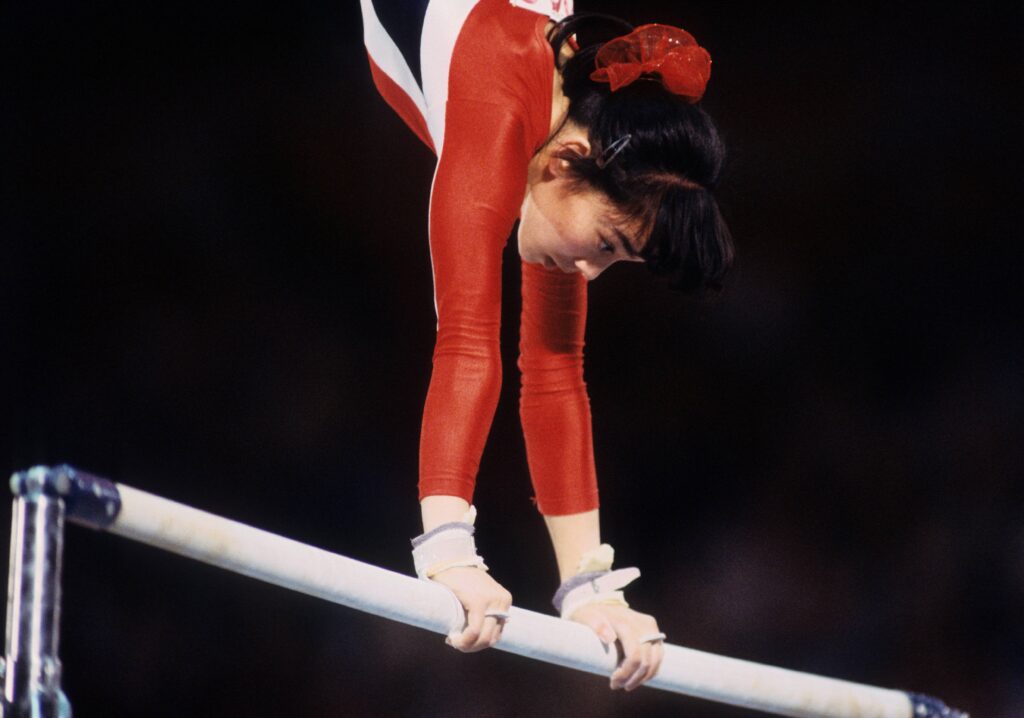

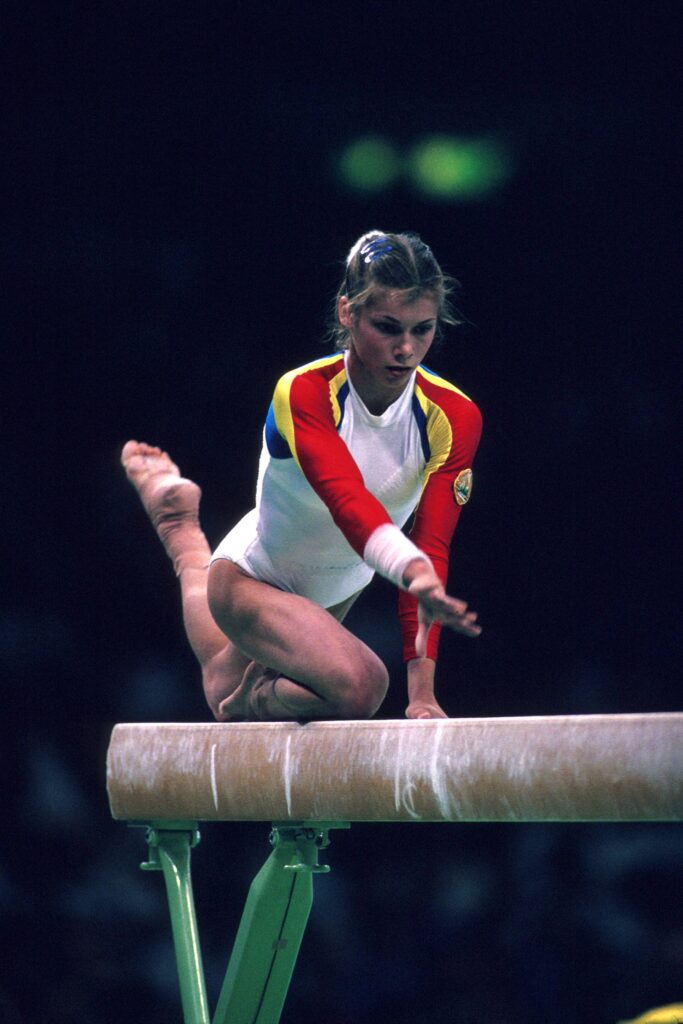

In 1986 and 1987, Chinese media presented Chen Cuiting as a gymnast perfectly timed for inheritance: the nation’s elegant answer to Romania’s Daniela Silivaș. Reporting from the Seoul Asian Games, a People’s Daily correspondent lingered on her “spring swallow” lightness, praising the ease with which she carried herself to the all-around title. Both that article and a subsequent China Pictorial profile placed her age at fifteen—young, but properly arrived.

The China Pictorial piece, published in February 1987, filled in the arc behind the moment. Born on July 15, 1971, in Changsha, Hunan, Chen had risen from a raw “tumblebug”—a nickname earned for her explosive tumbling—into a national champion who, as the magazine put it, had learned to “smile spontaneously to the music.” It was a familiar story of discipline refined into artistry, told at precisely the point when promise seemed to be turning into permanence.

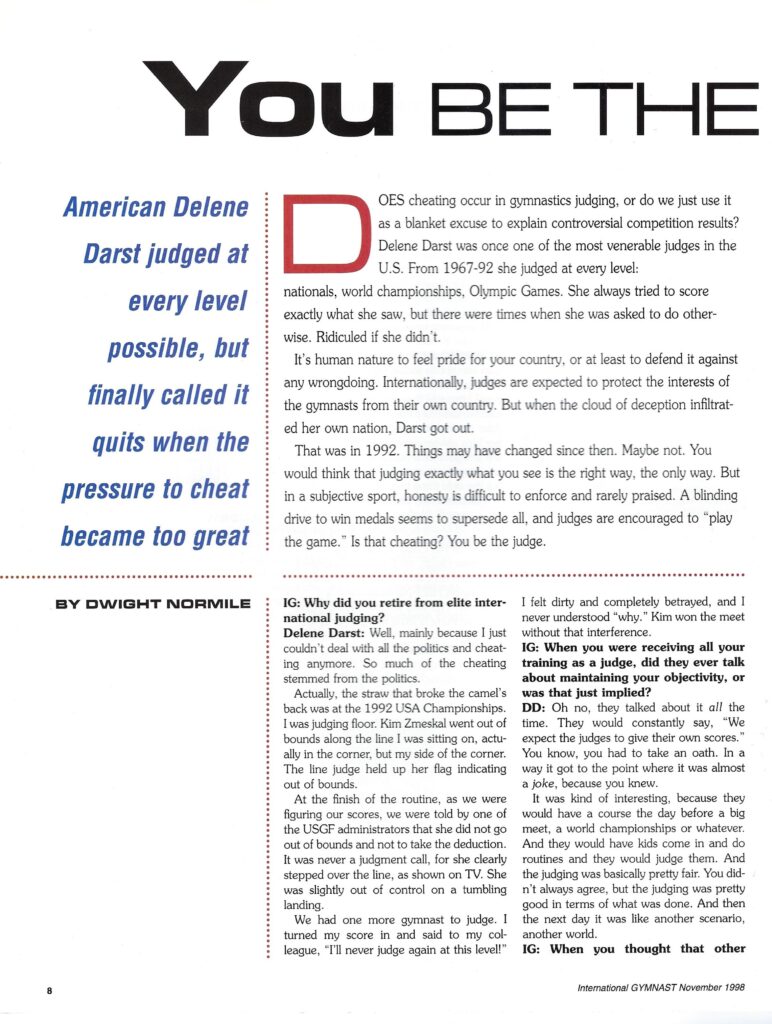

From today’s vantage point, however, that narrative no longer sits so easily. Across both Chinese- and English-language websites, Chen’s birthdate now appears as November 15, 1972. If accurate, she would have been only thirteen, turning fourteen, during the 1986 season—below the minimum age of fifteen required for senior international competition. The confident certainties of the mid-1980s press thus coexist uneasily with a digital record that rewrites the calendar.

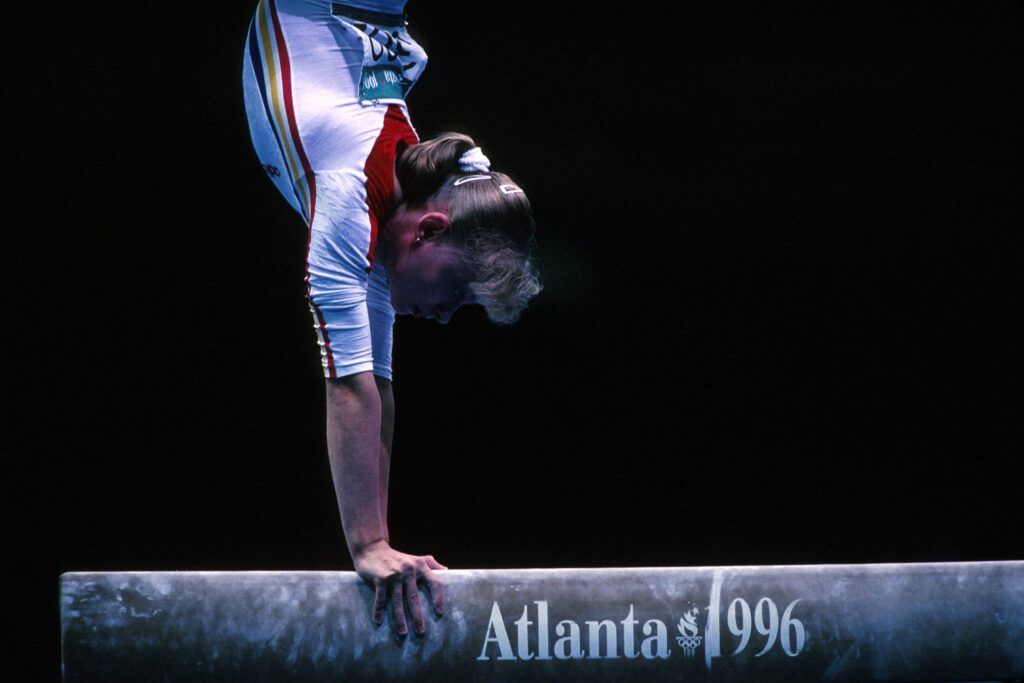

Whatever the truth of her age, Chen Cuiting’s competitive record is unmistakable. She dominated Chinese women’s gymnastics through the late 1980s, breaking out internationally at the 1986 Asian Games with team gold, all-around gold, floor gold, and vault silver. She remained the country’s leading all-arounder at home, winning the title at the 1987 National Games and the 1988 National Championships. Though her Seoul Olympics yielded no individual medals—fourteenth in the all-around, sixth with the team—she rebounded at the 1989 World Championships with team bronze and top-six finishes in the all-around, beam, and floor. Her career closed where it had begun to crest: at the 1990 Asian Games in Beijing, she again swept gold in the team, all-around, and floor, adding another vault silver before retiring. In just five years, she anchored the national team through a transitional era, her dominance unquestioned even as the story told about her grew more complicated.