In late January 1981, a Romanian gymnast, who was competing at the International Gymnastics Classic in Los Angeles, was greeted with something unusual: birthday cake. During a dinner with the delegations, someone mentioned the petite Romanian had a birthday, and the Americans—ever genial hosts—sang “Happy Birthday, Ecaterina.” She smiled. She stood. She accepted the applause.

There was only one problem. The gymnast wasn’t Ecaterina Szabó. It was Lavinia Agache.

What happened in California that weekend became known as the “Szabó Substitution”—a scandal that would expose gaps in international athletic oversight, raise questions about Cold War-era sports diplomacy, and leave a young gymnast’s achievements erased from the record. The story unfolds differently depending on whose version you follow, but the timeline itself reveals how information traveled, how institutions reacted, and what remained unresolved.

USGF News, no. 2, 1981

The Competition: January 31–February 1, 1981

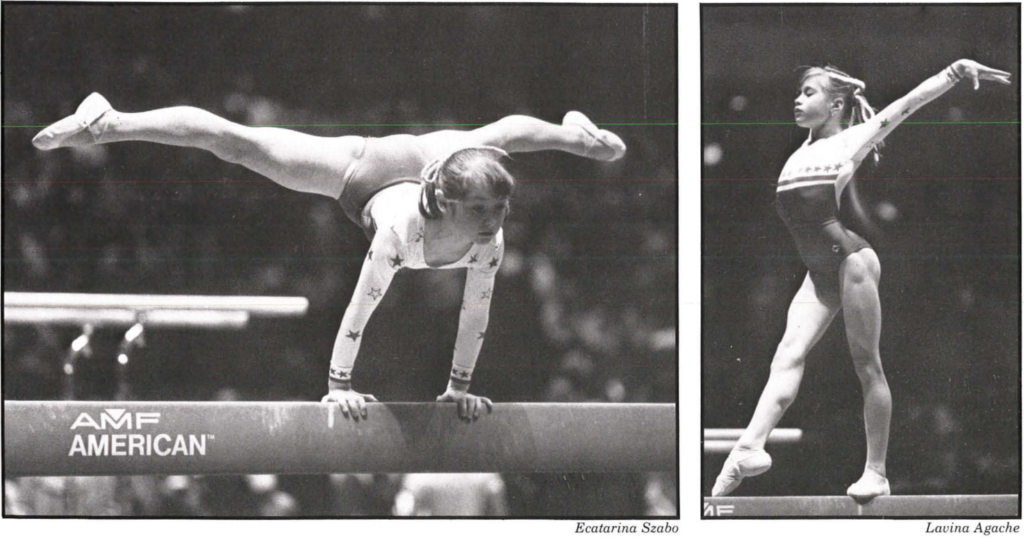

Mary A. Wright, reporting for International Gymnast and USGF News, described the gymnast competing as “Ecaterina Szabó” in purely athletic terms. On uneven bars, she wrote, the Romanian showed “versatility with giant swings and a double flyaway dismount.” On beam, “Ecaterina, a tiny ball of dynamite,” won the event with a score of 9.55.

The gymnast performed exactly as Szabó, the Junior European Champion, was expected to perform—spectacularly well. NBC cameras captured clean lines, strong tumbling, and confident dismounts. When Bart Conner, who finished 14th at the event, heard from U.S. gymnast Amy Koopman that this might not be Szabó, he asked the gymnast directly through an interpreter. She smiled and said, “Szabó.” Who was going to challenge a young girl?

The competition ended with “Szabó” placing third in the all-around with 37.80 points, behind Americans Marcia Frederick and Julianne McNamara.

The First Correction: February 3–5, 1981

On February 3, Romania’s main sports newspaper, Sportul, reported what many had believed: Ecaterina Szabó had won bronze at the Los Angeles meet. “Here are the standings,” the article stated. “1. Marcia Frederick (U.S.A.) — 38.25 pts; 2. Julianne McNamara (U.S.A.) — 38.15 pts; 3. Ecaterina Szabó (Romania) — 37.80 pts; 4. Trina Tinti (U.S.A.) — 37.30 pts.” The article praised “the young Romanian gymnast” for having “the best performance of the competition on beam.”

Two days later, Sportul printed a brief correction:

“Due to an incorrect piece of information picked up by the international press agencies, the ranking of the women’s gymnastics competition in Los Angeles did not appear according to the competition sheet. In the official ranking, third place in the all-around went to Lavinia Agache (Romania)—37.80 points.”

No explanation. No elaboration. Just a quiet adjustment of the record. It was Lavinia Agache who had actually finished third.

What would take American officials months to discover had been publicly corrected in Romania within forty-eight hours. The problem was that no one in the United States was reading Sportul. The correction went unnoticed, and for weeks, American officials did not revisit the issue.

The Discovery: March 1981

The truth became unavoidable when the Romanian team returned to the United States in March for the Nadia ’81 exhibition tour. This time, both Ecaterina Szabó and Lavinia Agache traveled with the team.

Bart Conner recognized the problem immediately. When the announcer introduced “Ecaterina Szabó,” a different gymnast took the floor—not the one he had met in Los Angeles. When “Lavinia Agache” was announced, there stood the girl from the January competition.

Judge Cheryl Grace, who had befriended Agache during the tour, asked about her previous trip to the United States. When Grace mentioned that Agache’s performance looked better on this tour than it had in Los Angeles, Agache offered an explanation. Through another Romanian gymnast who spoke English, she said: “Well, that’s because she was appearing as another gymnast, and she did not want the other gymnast to receive credit for the skills that she performs as Agache.”

It was not a full explanation. The comment arrived through layers of translation, and it’s impossible to know how freely she spoke. But it remains one of the only surviving accounts that gestures toward Agache’s own perspective. She simply wanted her best gymnastics to be recognized as her own, not as someone else’s.

NBC Investigates: April 1981

By April, NBC had assembled compelling evidence of the substitution. When the network’s Sports Journal program aired, Bryant Gumbel opened with footage of two gymnasts performing double tuck dismounts off beam, one after the other. The differences in body type, movement quality, and appearance were visible. Then the screen cut to side-by-side still images—two faces, two gymnasts:

“Is this Ecaterina Szabó, the European junior gymnastics champion from Romania? Or is this Ecaterina Szabó?”

Gumbel laid out the implications with disarming clarity. Lavinia Agache had “apparently” entered the United States using a passport that identified her as Ecaterina Szabó. Under U.S. federal law, anyone who knowingly aids someone in entering the country by impersonating another could face up to five years in prison or deportation.

How had this happened? The broadcast revealed a procedural vacuum. Roger Counsil, executive director of the U.S. Gymnastics Federation, acknowledged that in his thirty-some-odd years in gymnastics, passport checks at meets were virtually unheard of. “The only time that one would ever look at the passports of foreign athletes in a meet is to—well, obviously, if a question would come up about an identity, I think they would, but as I say, in my 30-some-odd years, I’ve never heard of such a thing, or for ticketing purposes.”

Don Peters, the meet director, had never actually seen the gymnast’s passport himself. When American gymnasts who had competed against Szabó in Japan insisted this was a different girl, Peters checked with his transportation staff. They told him that this was Szabó “because this kid had Szabó’s passport.” Peters relied on what others told him.

But what had those logistics coordinators actually verified? The NBC broadcast included interviews that revealed how little checking had occurred. Donna Ball, who handled hospitality, explained that when she went to the airport to collect return tickets, the airline needed passport numbers. “When I told this to the interpreter, he gave me the names and the passport numbers, and I took those back, and the name was Szabó,” she said. “The number, whether it corresponded from her passport, I can’t say, except that that’s what was punched into the airline computer.” She had received information from the Romanian interpreter, but couldn’t confirm whether those numbers actually matched any passport.

Rich Kenney, handling ticketing, described a similar process. He asked the Romanian interpreter for the correct spellings to ensure proper reservations. The interpreter gave him names, which he showed on camera. Kenney entered them into the system. No documents were examined. The U.S. staff members just acted out of trust.

Counsil later wrote that when questions about the gymnast’s identity arose, “the passport of Ecaterina Szabó was produced to the meet management personnel as evidenced by the Romanian delegation.” But the passive construction—”was produced”—left crucial details unspecified. Who saw it? When? What did they actually examine? The document’s presentation appears to have satisfied concerns without genuine verification.

The broadcast also revealed a troubling timeline. Multiple people—Grace, Koopman, Conner, Peters—recalled suspicions arising during the meet itself. Peters said a Romanian interpreter confirmed the deception the day after the competition ended. Yet Peters didn’t notify NBC, and the USGF’s executive director didn’t learn about the substitution until “some two months after the meet ended.” Information that should have traveled upward through the organization simply disappeared.

Beyond the question of how the substitution went undetected, NBC explored why it happened at all. Why would anyone substitute one talented gymnast for another equally talented one? Bart Conner offered a theory: “I have a feeling that the promoters and the people who set up the meet based a lot of the promotion and publicity on the fact that they would have the junior European champion from Romania, this Ecaterina Szabó.” Perhaps Szabó had been injured and couldn’t travel. But rather than request a substitution through proper channels, the Romanians simply sent Agache under Szabó’s name.

The contractual context mattered. The USGF had contracted with NBC to deliver specific athletes, including Szabó. While the contract included a standard clause allowing substitutions in case of illness or injury, such substitutions required notification. As Gumbel noted, “In this case, more than a substitution occurred; there was a misrepresentation by the Romanians, and that misrepresentation was good enough to deceive USGF officials, or so they say.”

At the center of the mystery stood Béla Károlyi, who could answer every question but wouldn’t speak. The legendary Romanian coach had defected to the United States at the end of March, along with his wife, Márta, and choreographer Géza Pozsár. But they had left behind their seven-year-old daughter, Andrea, in Romania. On advice of counsel, and because of his uncertain status as a defector—and his potential legal exposure—Károlyi declined to be interviewed.

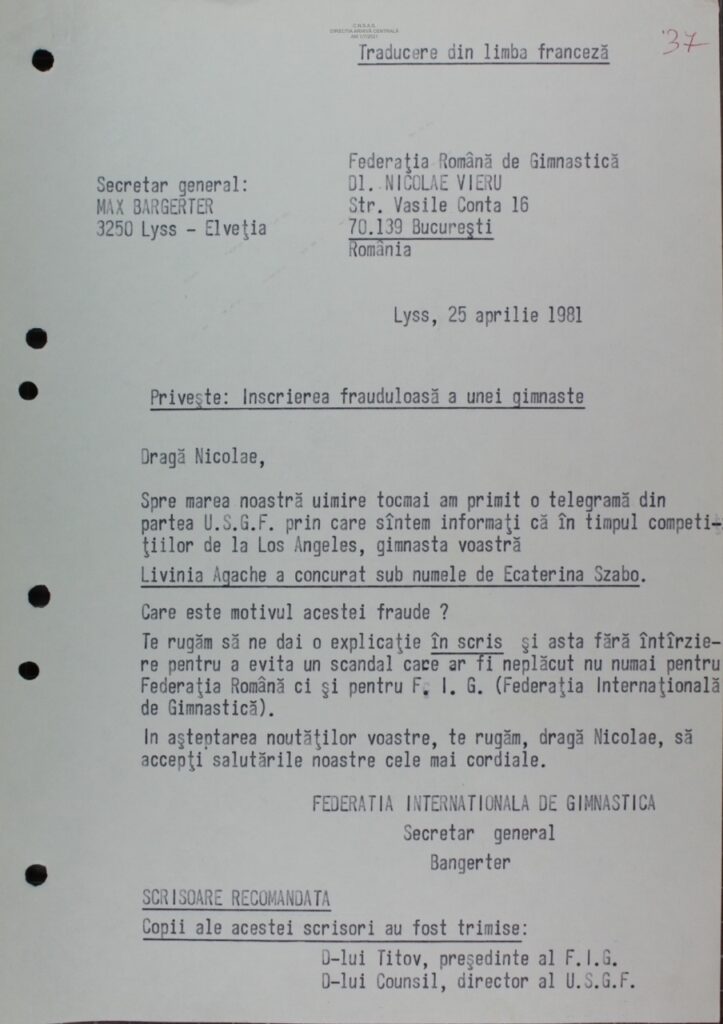

The FIG’s Response: Late April 1981

On April 25, after NBC’s broadcast, Max Bangerter, General Secretary of the International Gymnastics Federation, wrote to Nicolae Vieru, the president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation:

“To our great astonishment… during the Los Angeles competitions, your gymnast Lavinia Agache competed under the name of Ecaterina Szabó. What is the reason for this fraud? Please give us an explanation in writing, and this without any delay.”

The letter was marked “registered,” and copies went to FIG Chairman Yuri Titov and USGF Director Roger Counsil. This was now international federation business.

Speaking to the American press from Switzerland, Bangerter struck a more measured tone. The FIG needed more details before ruling, he said. “We must be very careful.” If the switch had taken place, both gymnasts could face bans from future world championships and Olympic Games. A decision would probably come in two or three weeks.

The decision never came. Despite Bangerter’s warning about potential bans, no action was taken against either gymnast. Lavinia Agache competed at the 1981 World Championships in Moscow that fall—technically in violation of age eligibility rules, as she was only thirteen. The substitution scandal, which had dominated headlines in the spring, quietly faded without resolution.

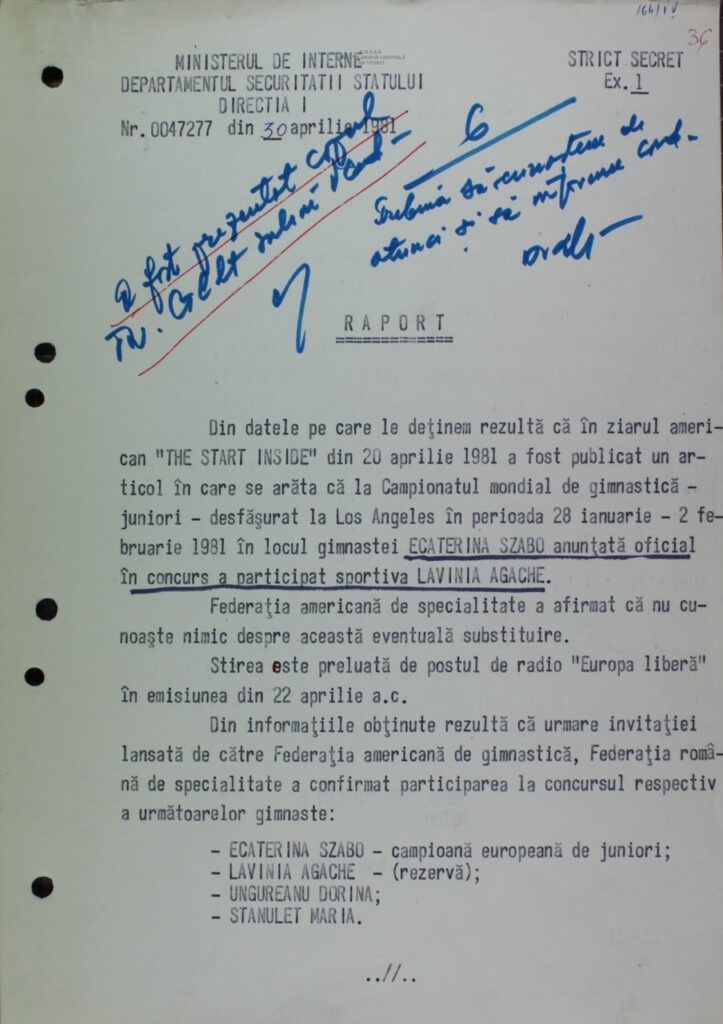

The Romanian Account: April 30, 1981

Five days after Bangerter’s letter, Ion Munteanu—a Romanian state security official—submitted an internal report explaining what had happened. According to Munteanu, the Romanian federation had originally confirmed that Szabó would compete in Los Angeles, with Agache listed as reserve. But for unspecified “technical reasons,” officials decided Agache would make the trip instead, accompanied by coach Béla Károlyi.

Crucially, Munteanu insisted that Agache had traveled legitimately: “Athlete LAVINIA AGACHE had the necessary passport formalities done and had the international transport documents purchased on a nominal basis.” Her passport, her tickets—all in her own name.

The substitution, Munteanu claimed, occurred only at the competition site—not during international travel or border control—and it was done by Károlyi: “At the instance of the US organizers from Los Angeles, who had previously made great publicity in relation to the European Champion ECATERINA SZABÓ, BÉLA KÁROLYI accepted that LAVINIA AGACHE would compete under the name of this athlete, without having any approval from the Romanian Federation in the field.”

When Agache placed third, international news agencies mistakenly credited the result to Szabó. The Romanian federation only learned of the problem afterward and published its correction in Sportul on February 5. Munteanu wrote, “Noticing this inconsistency, the Romanian Gymnastics Federation intervened and invalidated in the “Sportul” newspaper of February 5, 1981 the news published in the previous issue.”

Munteanu concluded that the case had “implications in particular on BELA KAROLYI, since the act is deemed to be a violation of the federal law and is punished with 5 years of imprisonment or expulsion—presuming the fault of the former coach.”

That phrase—”former coach”—was telling. Munteanu wrote this report after Károlyi’s defection, documenting the incident in a way that established Károlyi’s sole responsibility while distancing the Romanian federation from any culpability. Whether the account reflected genuine events or simply made Károlyi a convenient scapegoat for a debacle he could no longer defend himself against is impossible to know.

But Munteanu’s report created a fundamental contradiction. If Agache had traveled under her own passport with tickets in her own name, why would there be federal charges? And why did American officials consistently report the presence of Szabó’s passport? Between the Romanian claim and the American accounts lay a procedural vacuum—no verification protocols, no clear documentation, no answers.

Nullification: Spring 1981

After consulting with the FIG office in Switzerland, which concurred with the decision, the USGF eliminated both Szabó’s and Agache’s names from the final results and elevated other finishers by one position. The bronze medal that Sportul had first awarded to Szabó, then corrected to Agache, now belonged to American Trina Tinti.

Roger Counsil wrote in the federation’s news publication: “Because we are convinced there was a substitution made… we must eliminate the mention of either girl’s name from the final results.”

A podium finish vanished. The official record dissolved. No athlete or federation protested.

Counsil expressed lingering puzzlement over the motive. “Both girls are equally outstanding gymnasts,” he wrote. “In fact, it has been conjectured that Agache is a better gymnast than Szabó. Be that as it may, the quality of the competition would not have suffered by Agache competing under her own name.”

He also expressed discomfort with how the story had become public: “We are concerned as to why the incident happened and why it was sensationalized on NBC television because we see no logic for the ‘Szabó Substitution.'”

The remark suggested the USGF felt NBC’s coverage was excessive, though Counsil didn’t elaborate on what he found sensationalist about the broadcast. It was an odd complaint from an organization whose own internal communication failures had allowed the deception to go unreported for months.

What Remains Unresolved

The Szabó substitution exposed institutional failures on several levels. Lacking any procedure for confirming athlete identities, the Americans accepted the switch on nothing more than a verbal claim and the presentation of a passport. Once doubts emerged, they never moved beyond the competition floor; concerns stalled, went unrecorded, and ultimately dissolved. By the time the USGF’s executive director finally heard about the incident—two months later—the issue hadn’t been hidden so much as lost in a system that could not capture or transmit critical information.

The Romanians, for their part, corrected the record domestically within forty-eight hours. Internally, a secret Securitate report by Ion Munteanu blamed Károlyi alone for the switch and claimed Agache traveled on legitimate documentation. This not only undercut NBC’s narrative of criminal subterfuge, but also conflicted with American claims that Szabó’s passport had been presented. The truth of the passport episode sits somewhere in the murky space between dueling institutional accounts and the absence of any reliable verification process.

Károlyi never spoke publicly about the incident. His daughter, Andrea, eventually joined her parents in the United States and worked as a nutritionist at the Ranch later in life. Both Béla and Márta went on to build legendary and infamously controversial careers in American gymnastics. The questions he could have answered about the Szabó Situation remained unanswered.

But perhaps the most significant gap is Agache’s voice. When federations, television networks, and state authorities debated legality and responsibility, the athlete at the center had almost no say. In Romania of the 1980s, a thirteen-year-old gymnast would not have been permitted to speak publicly about such matters. Only a single mediated sentence from 1981 survives in the archive, spoken through another Romanian gymnast to an American judge during a tour. More than forty years later, we can hear—faintly, through layers of translation and institutional silence—that she wanted something simple: that the skills she performed would be recognized as hers.

So, here are some of the skills she performed in 1981.

⸻

A note on sources: This article mentions Don Peters, who organized the 1981 Los Angeles meet and later coached the 1984 U.S. Olympic women’s gymnastics team. In 2011, Peters was banned by USA Gymnastics and removed from its Hall of Fame after an investigation into sexual abuse allegations. Those later findings do not change the factual record of 1981, but they necessarily shadow any retrospective retelling.

Thanks: This article relies on the research of Jessica O’Beirne and Cosmic Bogdan, as well as the translations of Bea Gheorghisor. Thank you for sharing your work in the Securitate archives with me.

References

Counsil, Roger L. “The Mystery of the Romanian Substitution.” USGF News, no. 2, 1981.

“Gimnasta Ecaterina Szabó pe podium la Los Angeles.” Sportul 3 Feb. 1981.

“Gimnastică.” Sportul 5 Feb. 1981.

“NBC Uncovers Fake Gymnast at LA Meet.” Idaho Statesmen 20 Apr. 1981.

“People in Sports.” The Daily Breeze 29 Apr. 1981.

“USGF Certain of Gym Switch.” Fort-Worth Star Telegram 25 Apr. 1981.

Wright, Mary A. “International Gymnastics Classic.” USGF News, no. 2, 1981.

Appendix A: The Securitate Documents

Appendix B: The Full NBC Transcript

Bryant Gumbel: [00:00:00] The Sports Journal question for the day sounds like a sports version of To Tell the Truth. Is this Ecaterina Szabó, the European junior gymnastics champion from Romania? Or is this Ecaterina Szabó, the European junior gymnastics champion from Romania? The girl on the left-hand side of your screen appears to be the real Ecaterina Szabó. On the right, Romanian Lavinia Agache. On January 28th, Lavinia entered the United States, apparently using a passport that identified her incorrectly as Ecaterina Szabó.

Roger Counsil: The only time that one would ever look at the passports of foreign athletes in a meet is to– well, obviously, if a question would come up about an identity, I think they would, but as I say, in my 30-some-odd years, I’ve never heard of such a thing, or for ticketing purposes.

Donna Ball: I had to pick up the returning airline tickets for the Romanian gymnasts, and when I went out to the airport, they required that I needed the passport numbers. When I told this to the interpreter, he gave me the names and the passport numbers, and I took those back, and the name was Szabó. The number, whether it corresponded from her passport, I can’t say, except that that’s what was punched into the airline computer.

Rich Kenney: I asked them who exactly needs tickets. I need the correct spelling to get the proper airline tickets. This piece of paper is the one that the interpreter wrote on in the correct spelling, which I requested, the names of the people that needed tickets to return to Romania.

Bryant: Lavinia came to the States pretending to be Ecaterina in order to compete in the International Gymnastics Classic in Los Angeles. Her teammates and her coach, Béla Károlyi, played their part in the deception.

Donna: [00:02:00] Several of our coaches had birthdays in and around that weekend, so we were singing happy birthday to them, and somebody mentioned that it was, in fact, what we thought of as Szabó at the time, it was her birthday. Being congenial hosts, we decided, hey, let’s sing happy birthday to her, and she stood up, and we sang happy birthday, Ecaterina. Well, now I don’t know whether Ecaterina’s birthday was, in fact, that day, and she was in Romania, or whether it was the girl who was there, and we sang to somebody. I don’t know where she was, but we did sing Happy Birthday to her.

Bryant: There were a few people at the meet in Los Angeles who questioned Lavinia’s identity, but no one seemed suspicious enough to pursue the point.

Bart Conner: One of the other girls who was at the competition from the United States team, Amy Koopman, told me at dinner table that this wasn’t Szabó. She had seen Szabó before, and this wasn’t the same girl. I said, “Well, why don’t we just ask her?” I figured that’d be the best way to find out. The little girl was sitting next to me, and [00:03:00] Emilia Nikola, who is the junior men’s champion, was also sitting there. I asked him because he could speak English. I said, “Well, what’s her name?” He said Szabó. I looked at her, and she said Szabó and smiled right back at me. Of course, we believed that it was actually Szabó. We went through the whole competition, everybody praising how good this little gymnast was from Romania.

Cheryl Grace: As a judge, I’ve been seeing international gymnasts on a regular basis, either through photos or through competition. When she began the competition, I recognized her as not being Szabó, but I was still a little bit uncertain in my mind that it wasn’t her.

Don Peters: The first suspicions that I had were during the competition. Some of the girls in the competition had been to an earlier meet in the fall in Japan, where Szabó competed. They said that this girl that was at the meet was not Szabó. I didn’t know, so I checked with some of our people who had handled the transportation, picking them up at the airport and putting them in their hotel, and whatever. They said that now this was Szabó because this kid had Szabó’s passport.

Bryant: Ecaterina, or the so-called Ecaterina, placed third in the competition and returned to Romania. By then, there were Americans who suspected that there was something wrong.

Don: The day after the competition, the interpreter told me that, that was not Szabó in the competition.

Bryant: Then on March 5th, the Romanian team came back to the United States, first for an exhibition tour called Nadia 81, and then to compete in the American Cup. Coach Károlyi was with his team, only this time the real Ecaterina was there, and so was Lavinia. Both performed, and this time the previous deception could no longer be kept quiet.

Bart: [00:05:00] I went and participated in some of the performances, and I noticed that they announced this next girl up would be Ecaterina Szabó. I looked out there to see the friend that I had from Los Angeles, and it wasn’t the same girl. I started looking around, and they announced the next girl up is Agache, Lavinia Agache. I looked, and that was the girl who was at the meet in Los Angeles.

Cheryl: While we were on tour, I got to be friends with Lavinia Agache. We were trading information, and she was teaching me Romanian. I was teaching her English. We brought out the map of the United States, and we went over the places that we were going to be on on the tour. I asked her if she had been through this other gymnast, Dumitrița. I asked her if she had been anywhere else in the United States, and she said, “Yes, Los Angeles.” I told her that her performance that I had seen on the tour was much better than in Los Angeles. Again, through the Romanian gymnast that spoke English, she said, “Well, that’s because she was appearing [00:06:00] as another gymnast, and that she did not want the other gymnast to receive credit for the skills that she performs as Agache.

Bryant: At the end of the tour, Coach Béla Károlyi, his wife Márta, and team choreographer Géza Pozsar defected to the United States. Ecaterina and Lavinia went home without their coach, leaving behind many unanswered questions. Why the substitution took place is a question only Béla Károlyi can answer. On the advice of his counsel, and because of his uncertain status as a defector, Mr. Károlyi has declined to be interviewed.

You see, when the Károlyis defected, they left behind their 7-year-old daughter, Andrea, in Romania. They naturally prefer to remain silent, at least until her status is resolved. There are others involved, besides the Romanians, who can speak, who are accountable as well, and who can shed some light on how this happened, and perhaps why it happened.

Roger: I am surprised that it happened because, again, I don’t understand why it happened. I still don’t understand why the substitution was made. It’s not particularly alarming that someone would do this because I feel that when all is said and done, we may find out it was something as simple as an expedient on the part of the Romanian coach to go ahead and have competition, and he didn’t realize the consequences of what he was doing.

Bart: I have a feeling that the promoters and the people who set up the meet based a lot of the promotion and publicity on the fact that they would have the junior European champion from Romania, this Ekatrina Szabó. I know that she had been hurting part of the year, and so she might have had an injury problem or something, and couldn’t show. I believe the Romanians decided to bring another gymnast. I don’t know where the mix-up came as to whether they decided that they would call her Szabó for the weekend or whether the promoters encouraged them to call her Szabó for the weekend.

Bryant: There is a contract for last January’s Los Angeles meet between the United States Gymnastics Federation and [00:08:00] NBC Sports, which specifies that Ekatrina Szabó, among others, would compete in Los Angeles. The contract also says that a request for a substitution could be made in the case of illness or injury. In this case, more than a substitution occurred; there was a misrepresentation by the Romanians, and that misrepresentation was good enough to deceive USGF officials, or so they say.

Roger: We did not knowingly sanction a fraud, nor were we aware until a considerable length of time after the meet that the possibility of a fraud had taken place.

Bryant: The fact remains that a deception took place, and the probability is that the United States law was broken. Now, the Federal Criminal Code states that anyone who knowingly aids or causes a person to enter the United States, impersonating another, could be found guilty of criminal fraud. If prosecuted for such fraud, any violators, including Béla Károlyi, could face up to five years in prison or under another [00:09:00] federal statute could face deportation.

Don: Béla was a participant in the fraud. He knew those children. He knew that girl wasn’t Szabó, et cetera, and he passed her off as Szabó as an agent of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation. At that time, he was in their employ, and he was possibly following orders from somebody above. If it was a contractual thing, possibly the head of the Federation told him to do this. In this particular instance now, since then Béla has defected to the United States, and he’s somewhere in the United States and hiding right now. I would hate to see this be in any way a bad mark on him because he may have not done this willingly.

Bryant: The Romanian gymnasts have gone, and they have taken some unanswered questions with them, but these facts remain. One, the presence of Ecaterina Szabó and other gymnasts was required by the contract between the USGF and NBC. Two, Lavinia Agache impersonated Ecaterina Szabó in the International Gymnastics Classic. Three, it appears Ms. Agache entered and left this country using a passport that identified her as Ecaterina Szabó. Four, although the meet director, Don Peters, learned of the fraud the day after the meet ended, he did not notify NBC of the fraud, nor was NBC ever notified of such by any USGF official. Five, the USGF denies any prior knowledge of the deception.

Now, all this we know as fact. The unanswered points perhaps could be resolved by Béla Károlyi, but he remains a silent figure, and understandably so. Not only is his daughter Andrea still in Romania, but if he knowingly participated in the fraud, he could face legal penalties.

Now, why did Lavinia masquerade as Ecaterina? Who made the substitution, [00:11:00] and what did they stand to gain? Did Béla Károlyi have a choice or a voice in the decision? Was the substitution perhaps even an opportunity for Károlyi to plan his defection, which was to come two months later? All those points of the mystery must, for the moment, remain unsolved, but we will continue to pursue the end of this story and keep you updated on the developments as well as Béla Károlyi’s status. I’m Bryant Gumbel for Sports Journal.

[00:11:26] [END OF AUDIO]

Appendix C: Romania’s Response to the FIG

Dear Sirs,

We acknowledge receipt of your letter of 23rd April, 1981.

Answering the question of your letter, we are sending you here enclosed the translated copy we sent to Mr. Max Bangerter, General Secretary of the FIG.

With our best cordial regards, I remain

Sincerely yours,

M. Vieru

Federation Internationale De Gymnastique

M. Max Bangerter, Secretaire General

Lyes, Switzerland

Dear Mr. Bangerter,

I was much surprised receiving your letter regarding the Los Angeles gymnastic competition, both for its terms and for the accusations brought upon our federation.

As it appears from the official correspondence we exchanged with the U.S. Federation, we notified this federation by a cable sent on 27th Jan. 1981 of our gymnast Cristina Grigoras’ participation, but as she became unavailable at that moment, our federation has decided to replace her by Lavinia Agache, to whom a passport and an air ticket have been duly issued.

I would like to stress that no written paper has been received until now from the American Federation reporting that at the concerned competition a substitution would have been made. As a matter of fact, the organizers who had the control of the competition, would have been able to check up and validate the concerned gymnast’s identity even from her arrival to the U.S., on the basis of her passport and air ticket, which cost would have to be refunded to our federation.

If at the said competition, at a given moment, a replacement was operated, the “fraud” to which you refer in your letter does not belong to our federation. Therefore, our federation has no idea of the subject of your letter and could be not responsible for actions or events happened without being informed or without its agreement.

We once again express our indignation for such offending accusations, which we reject and which have nothing to do with our federation’s activity in its foreign relationship.

I would be much obliged if the copy of my letter would circulate to all those concerned.

Sincerely yours,

N. Vieru

(As printed in International Gymnast, August 1981)

More on Romania

2 replies on “The Szabó Substitution: How Agache Competed as Szabó in Los Angeles”

That FX routine is so so so Pozsar coded…

Fascinating article

Another great article.

Here is how the late Linda McNamara remembered the switch. Linda McNamara was a coach at SCATS and assistant to National/Olympic coach Don Peters from 1979-93.

“The USGF approved the invitational concept and awarded the competition to SCATS in Huntington Beach, CA. SCATS then had to secure a venue for the event – be damned if I can remember which one it was though – they all run together after a while. Once the venue is secured the promotion of the competition begins. Confirm with Karolyi that yes, among others, Ecaterina Szabo, Jr European Champion, will be on the competition squad.

Begin producing promotional items, such as posters, to advertise the competition. Every single poster has Ecaterina Szabo on it. Every promotional piece in the media touted Szabo. Tickets were sold because the Americans wanted to see Szabo. Please remember that there was no internet at that time and that, while everyone knew the big names, most of us weren’t able to pick them out of a line up. Remember also that Szabo was the newly crowned Jr European Champ so almost no one had seen her. Ticket sales are boosted by the very name of Szabo.

Arrive Team Romania. Present the roster. Introduce the gymnasts – including Szabo. Wine, dine and entertain the team and its coaches. Peters even takes Karolyi hunting. An event which, in 1988 after all of the O-Team coaching hoopla, prompted Peters to quip: “I shoulda shot him when I had the chance.”

On the day of the competition you do the usual checks and confirm that everyone’s is still healthy and no one is missing. Nope, no one missing AND . . . btw, it’s Szabo’s birthday. The entire crowd stands and sings Happy Birthday to “Szabo”. Competition begins, USA gets it’s ass whooped and Romania wings its way back home. End of story?

Not end of story:

Monday morning I walk into the gym to a shit storm of reporters from NBC demanding to know why SCATS duped the public. Why hadn’t WE told anyone that it wasn’t really Ecaterina Szabo competing but, instead, Lavinia Agache? We are gobsmacked AND on the phone to USGF and they, in turn, are on the phone with Romania. SCATS representatives are in the lobby of the gym dancing as fast as they can with NBC until an explanation comes through.

Karolyi’s explanation was that Szabo wasn’t in top form so he decided to bring Agache instead. It was easier, he said, for her to fly on Szabo’s passport because there was no time to change tickets. To compete as Szabo rather than go to the trouble of informing the US was also easier. “We do it all the time. Why is there so much trouble about it?” . . . and, yeah, ok – why did we also end up singing HBD to the little girl who wasn’t there?

I don’t know if it’s the mindset of a dictatorial subject as opposed to that of a democratic subject or whether it is a matter of one giant do-whatever-I-want ego against the world. Either way it was wrong. It was also just one of the many reasons the US coaches didn’t embrace Karolyi upon defection.

Roger Counsil, Executive Director of the USGF, wrote in the USGF magazine, p.7, “ However, their minds were put at ease when coach Karolyi assured the meet management the competitor was indeed Ecaterina Szabo. In fact, the passport of Ecaterina Szabo was produced to the meet management as evidence by the Romanian delegation…We hope in the future the integrity of the sport is maintained by coaches and officials alike and that the reputation of all athletes are not jepordized by such arbitrary and unprincipled actions”.