In 1949, the Men’s Technical Committee published its first Code of Points.

Almost 10 years later, in 1958, the Women’s Technical Committee published its first Code of Points.

Of course, women’s gymnastics had rules before this. But this was the first official Code of Points, and as we’ll see, the rules for women’s artistic gymnastics had developed a lot since female gymnasts first competed at the Olympics in 1928.

Let’s take a look at the 1958 Code of Points.

An Overview of the 1958 Code of Points

General Info

- 5 judges per event

- Drop the high and low scores

- Final score: average of the middle 3 numbers

Note: In 1968, the Women’s Technical Committee adopted the men’s judging system: 4 judges with one superior judge.

Point Differentials

- The spread between the middle three scores could not exceed 0.5 if the scores were greater than 8.5.

- The spread between the middle three numbers could not exceed 1.0 in all other cases.

Scoring

Compulsory Routines: 10 points

- For uneven bars, beam, and floor:

- 5 points for rhythm and exactness

- 5 points for general impression (elegance and sureness of execution)

- For vault

- 5 points for the technical value

- 5 points for the execution

- Additional Info

- Repetitions: With the exception of floor, gymnasts could repeat the compulsory routines.

- The score for the second routine counted.

- Note: This allowance was abandoned in 1968 by both the Men’s Technical Committee and the Women’s Technical Committee.

- For the compulsory routines, each routine was broken into several parts, and each part was assigned a value based on its difficulty.

- Repetitions: With the exception of floor, gymnasts could repeat the compulsory routines.

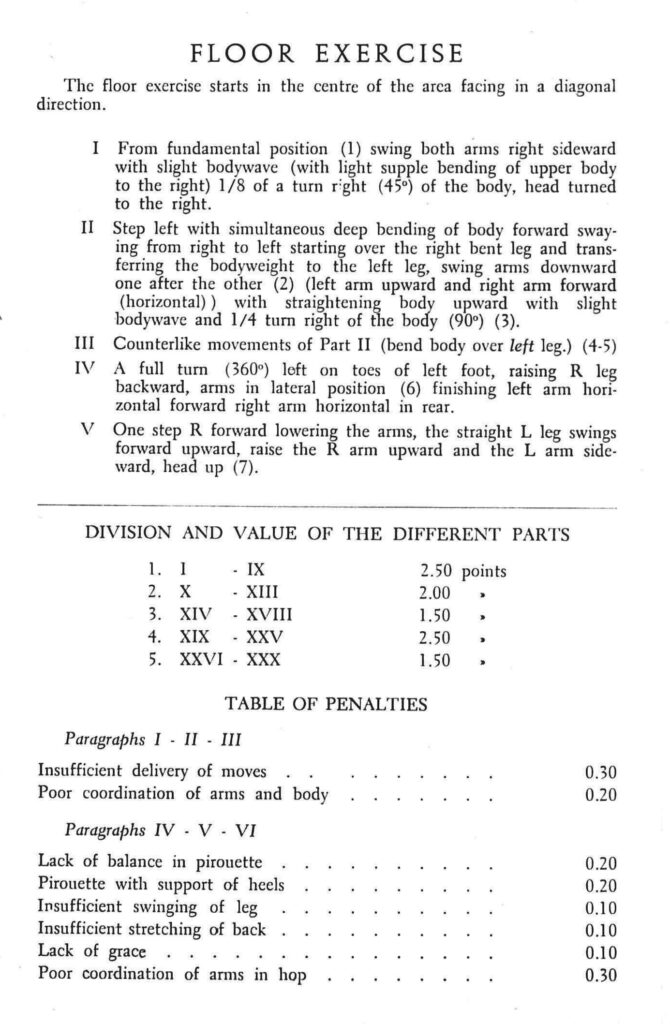

To give you an idea of how this worked, here’s the opening of the 1960 compulsory floor routine.

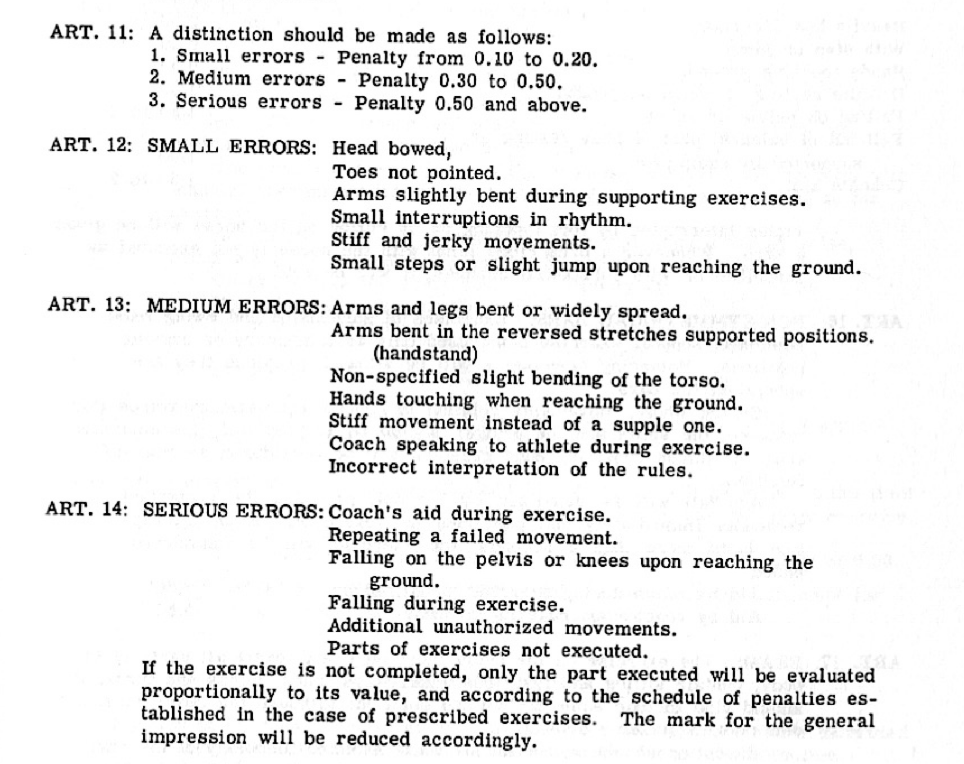

Optional Routines: 10 points

- 5 points

- 3 points for the difficulty

- 2 points for the technical value (composition)

- 5 points

- 2 points for the execution

- 3 points for the general impression

For additional deductions, read through the Code of Points below.

A Note on Difficulty

- 5 elements of difficulty

- 1 of those elements must be of the most difficult kind

- 0.6 deduction for each missing difficult element

- If no difficulty is included, a 3-point deduction could be considered

To get an idea of the level of difficulty required, jump to the “Progression of Principal Difficulties” from 1961.

Note: If a gymnast performed more difficulty than necessary with poor form, the judges weren’t always lenient, as was the case with Japanese gymnast Ikeda Keiko at the 1960 Olympics.

Composition Requirements

General Composition Requirement: Strength exercises were considered undesirable.

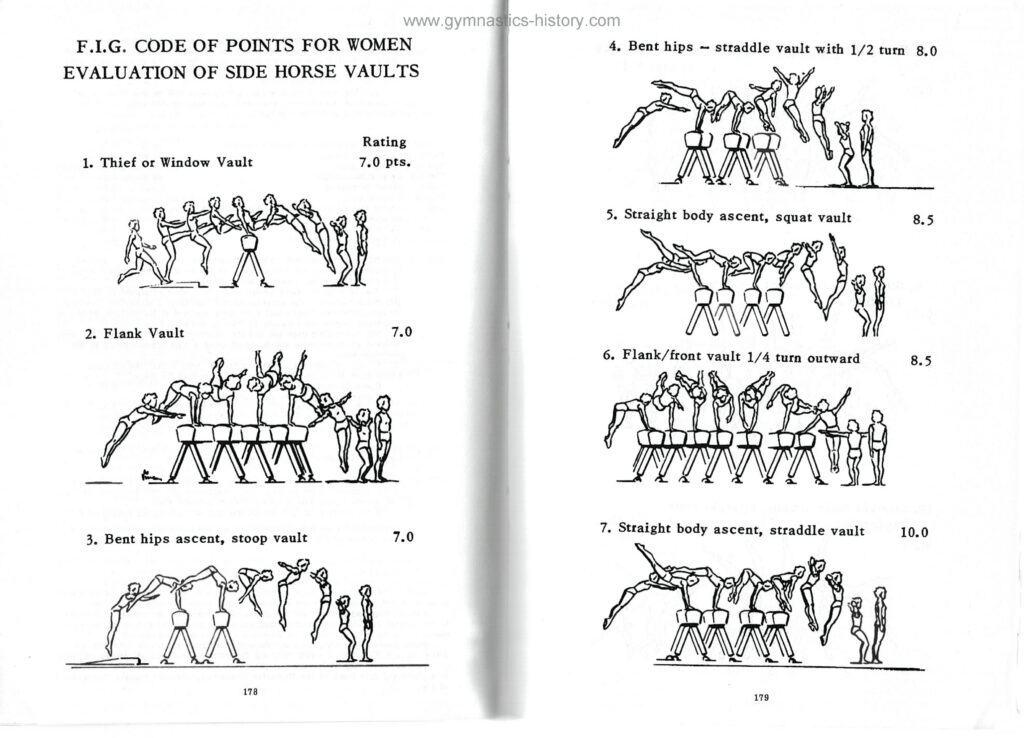

Vault

- Gymnasts had to place their hands on the vault

- Two attempts for compulsories and optionals; the best score counted

- For optionals, gymnasts could perform two different vaults

For the vault values, see the Code of Points.

Uneven Bars

- Predominantly swinging and hanging elements

- Support elements should be temporary

- Balancing movements were allowed if they were unique to bars (no splits or bridges)

- Falls were a 1 point deduction with 3 seconds to remount the apparatus

Beam

- Should be lively

- Use all parts of the body

- Include sitting and lying positions

- Include steps, runs, jumps, and turns

- Include static hold positions that do not dominate the routine

Falls are a 1 point deduction with 3 seconds to remount the apparatus.

Time: 1:30 to 2:00 minutes

Note: There were no specific acrobatic requirements for beam or floor. However, the compulsory routines included acrobatic elements, and gymnasts performed acrobatic elements to meet the difficulty requirements for their optional routines.

Floor

- Should be lively

- Include artistic movements and jumps

- Note: The French text uses the word “sauts,” which can mean jumps or tumbling. The AAU translated it as “jumps” in English.

- Include attractive poses, motions, and expression

- Should be set to music that corresponds to the exercise being performed

Time: 1:00 to 1:30

A Note on Music

The 1958 Code of Points specified that individual floor routines should be performed to music — and that’s important.

Nowadays, we can’t imagine women’s floor routines without music. However, that was not always the case. While ensemble routines had often used music before 1958, including at the 1928 Olympics, individual floor routines had not. In fact, as we saw at the 1950 Congress, many were against it.

So, in many ways, we have the 1958 Code of Points to thank for establishing the tradition of using floor music.

A Note on Boards

The Code of Points required a “hard board” (“tremplin dur“) for balance beam and bars. The 1964 Code of Points changed that, requiring a Reuther board.

A Note on Perfection

Interestingly, there’s no mention of perfection in the very first women’s Code of Points, but there was in the first men’s Code of Points.

Download the 1958 Women’s Code of Points

The French Text

Published in Le Gymnaste, no. 2, 1958. Courtesy of the BnF.

The AAU’s English Translation

Note #1: The English text is an unofficial version of the Code of Points translated by the Amateur Athletic Union in the U.S. The French text would have been considered the official version.

Note #2: The AAU published their translation long after the Code had been adopted. Failing to disseminate information was one of the critiques of the AAU when the United States Gymnastics Federation (USGF) was trying to establish itself as the official governing body in the U.S.

The 1961 Progression of Principal Difficulties

The Women’s Technical Committee divided skills into “basic” skills and “international groupings” (skills of higher difficulty).

However, the WTC was quick to note that these categories were porous and that basic skills could become more difficult depending on the connections:

It is a delicate matter to evaluate the degree of normal difficulties contained in these gradations, because of the evolution in feminine technique. The beauty of transitions equal to, if not greater than, the difficulties themselves, the originality of the bridges that come before and between the component parts, can, through their form, transform a simple maneuver into a genuine difficulty.

Examples of “international grouping” skills were back tucks on floor or back tucks off beam. You can read all of them below.

Note: The Women’s Technical Committee continued to use the labels “basic” and “international grouping” in the 1964 Code of Points but abandoned them in the 1968 Code of Points.

3 replies on “1958: The Very First Women’s Code of Points”

Amazing to see how far the sport/code of points has come! Thank you, very interesting. Do you have information about the earlier judging symbols/notation?

Very interesting. I am looking at the same information as Renee.

What’s the history for judging symbols. Who first used it and why?

I would assume that it was related to the increase of difficulty and rapidity, and for more supporting facts for notation?

The 1989 MAG Code of Points was the first to include the symbols. The WAG Code of Points followed suit in 1993.