In 1968, the Women’s Technical Committee President Berthe Villancher visited the United States. During her tour, she explained the 1968 Code of Points. This included her unwritten rules and preferences.

Let’s take a look at what she said.

Note: Villancher’s comments have been filtered through Jackie Uphues, who chronicled Villancher’s time in the United States for Mademoiselle Gymnast May/June 1968. (Jackie Uphues might be better known as Jackie Fie to some readers.)

Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes are from Mademoiselle Gymnast May/June 1968.

What does the women’s technical committee do?

It is exclusively composed of women, and it has two parts:

- The Women’s Committee has a representative from each of the 60 member federations

- The Women’s Executive Committee has 7 members

- To avoid bias, the members of the Executive Committee do not represent the interests of their individual countries

Specifically, the Women’s Executive Committee is in charge of:

- Preparing the compulsories for the World Championships and Olympic Games

- Directing the Olympic, World Games, and European Competitions

- Supporting all member Federations and gives help when needed

- Determining technical rules and prepare the Code of Points

- Training judges

- Directing gymnastics on a world-wide level

- Keeping an up-to-date file on each international judge

Oh, and they make “an effort to see that gymnastics is a feminine sport.”

What did Villancher think of excess difficulty?

Unlike the men, who were actively seeking more risk and difficulty, Villancher was against it:

Do not add extra difficulties beyond the required number as this opens the gymnast to more faults and deductions. Gymnasts of a low caliber should do what they are capable of and do this with perfection. Do not attempt what you are not ready for or can not perform with absolute sureness.

Note: The tradeoff between risk and execution was a constant theme in Villancher’s writing throughout the 1960s. In 1961, after the Olympics in Rome, she reflected on a decade of women’s gymnastics. Her report called the Japanese gymnasts “imprudentes” (“imprudent”) for taking unnecessary risk, which opened them up to unnecessary execution deductions:

the Japanese gymnasts, dazzling and imprudent, preferring supplementary acrobatics to the wise safety of the required level of difficulty, which, without bringing them any points, makes them risk getting deductions

les gymnastes japonaises éblouissantes et imprudentes, préférant à la sage sûreté des difficultés obligatoires, des acrobaties supplémentaires, qui, sans leur apporter de points, leur font risquer des pénalisations

L’Express, May 26, 1961

Villancher then singled out Ikeda Keiko:

In Rome, the experience of the Japanese gymnast Ikeda is conclusive: the number of difficulty elements was set at five, and, for having taken additional risks, she lost execution points.

A Rome, l’expérience de la Japonaise Ikeda est concluante: le nombre des éléments de difficultés était fixé à cinq et pour avoir pris des risques supplémentaires, elle perdit des points à l’exécution.

L’Express, May 26, 1961

Note: That is one interpretation of what happened during the 1960 Olympics. But it wasn’t the only view. Here’s what Japanese newspapers wrote about Ikeda’s routines at the Olympics in Rome.

Another way to think about it: Villancher stayed true to the original 1949 Code of Points, which stated:

Les exercises trop difficiles que le gymnaste ne parvient à exécuter qu’avec peine ou incomplètement, seront taxés sévèrement, car en gymnastique artistique, le gymnaste doit pouvoir maitriser son corps ave élégance et sûreté.

Exercises that are too difficult for the gymnast to perform completely or without difficulty, will be deducted severely because, in artistic gymnastics, the gymnast must be able to control his body with elegance and surety.

Men’s Code of Points, 1949

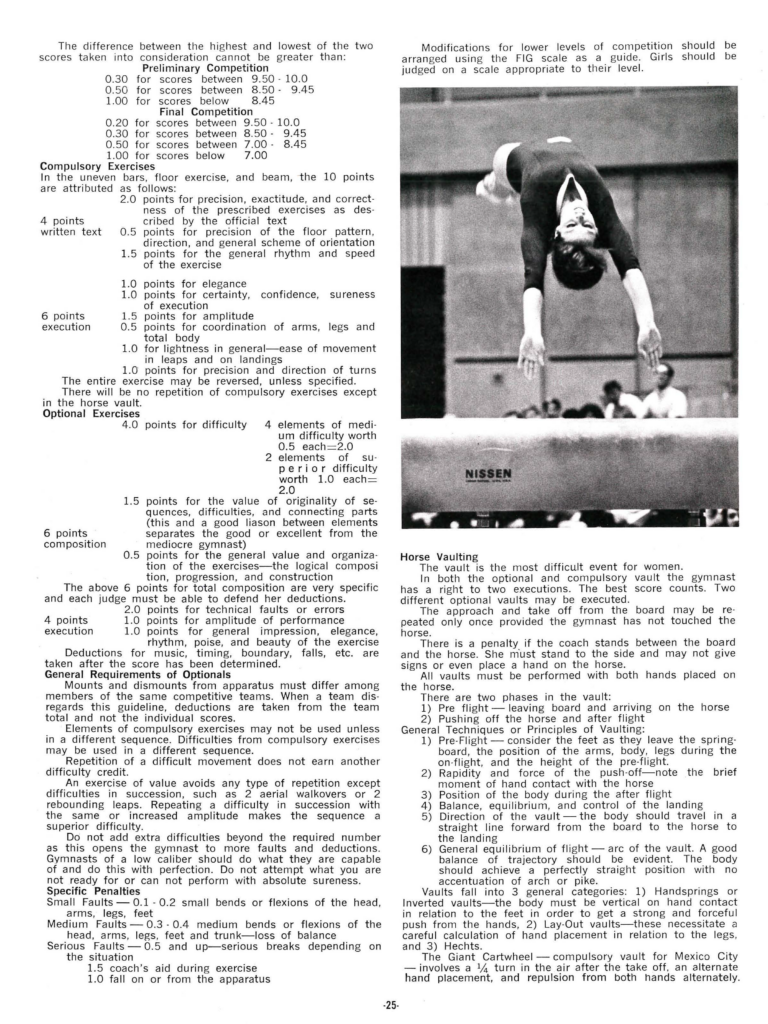

What did Villancher prefer — a high pre-flight or a high post-flight on vault?

It was rumored that she preferred a high post-flight.

In 1969, Dale Flansaas, the U.S. Women’s National Coach, wrote an article about a meet between Japan, the USSR, and the U.S.A. In it, she wrote:

One of the Japanese officials told me that Mme. Villancher commented that she preferred the style with more post-flight (she officiated the meet).

Mademoiselle Gymnast, Nov./Dec. 1969

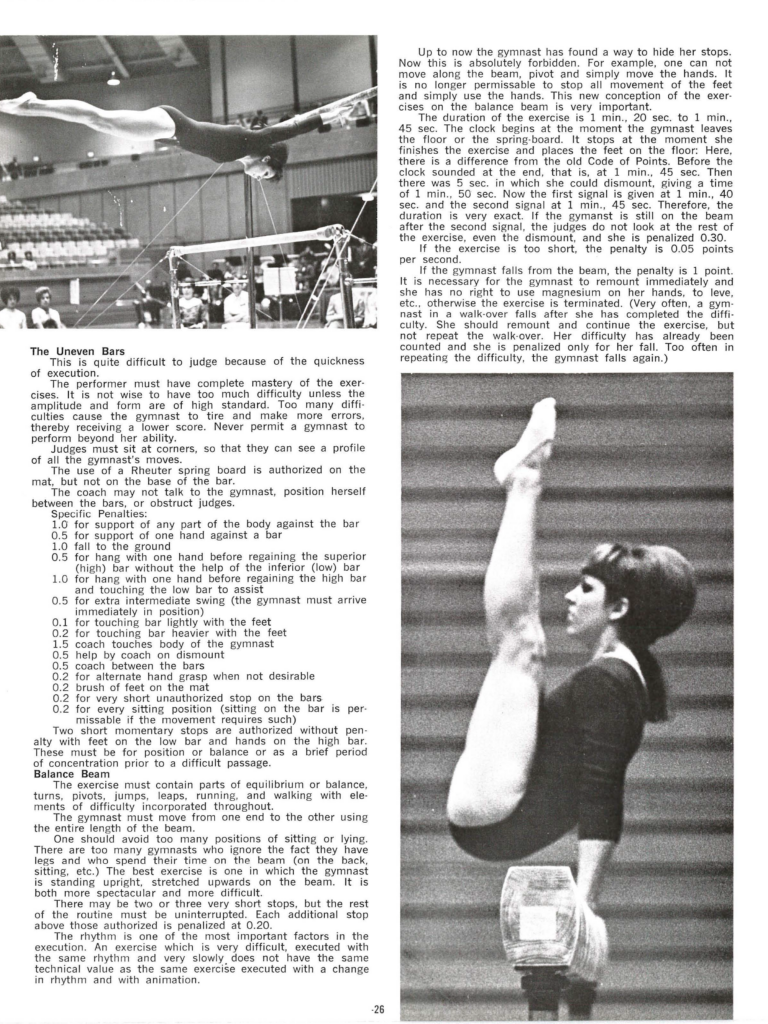

What did Villancher think about gymnasts who sit on the beam a lot?

There are too many gymnasts who ignore the fact they have legs and who spend their time on the beam (on the back, sitting, etc.) The best exercise is one in which the gymnast is standing upright, stretched upwards on the beam. It is both more spectacular and more difficult.

Should gymnasts plan on being out of breath and choreograph accordingly?

Short answer: Yes.

Long answer:

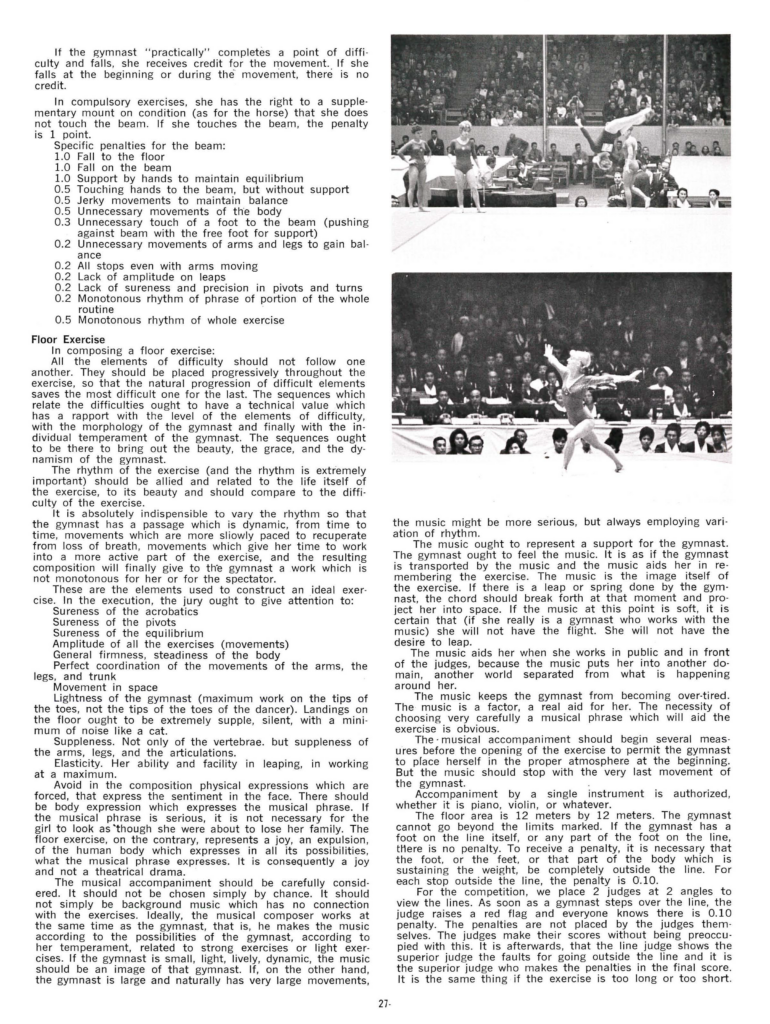

It is absolutely indispensable to vary the rhythm so that the gymnast has a passage which is dynamic, from time to time, movements which are more slowly paced to recuperate from loss of breath, movements which give her time to work into a more active part of the exercise, and the resulting composition will finally give to the gymnast a work which is not monotonous for her or for the spectator.

How does Villancher feel about loud landings?

No!

Landings on the floor ought to be extremely supple, silent, with a minimum of noise like a cat.

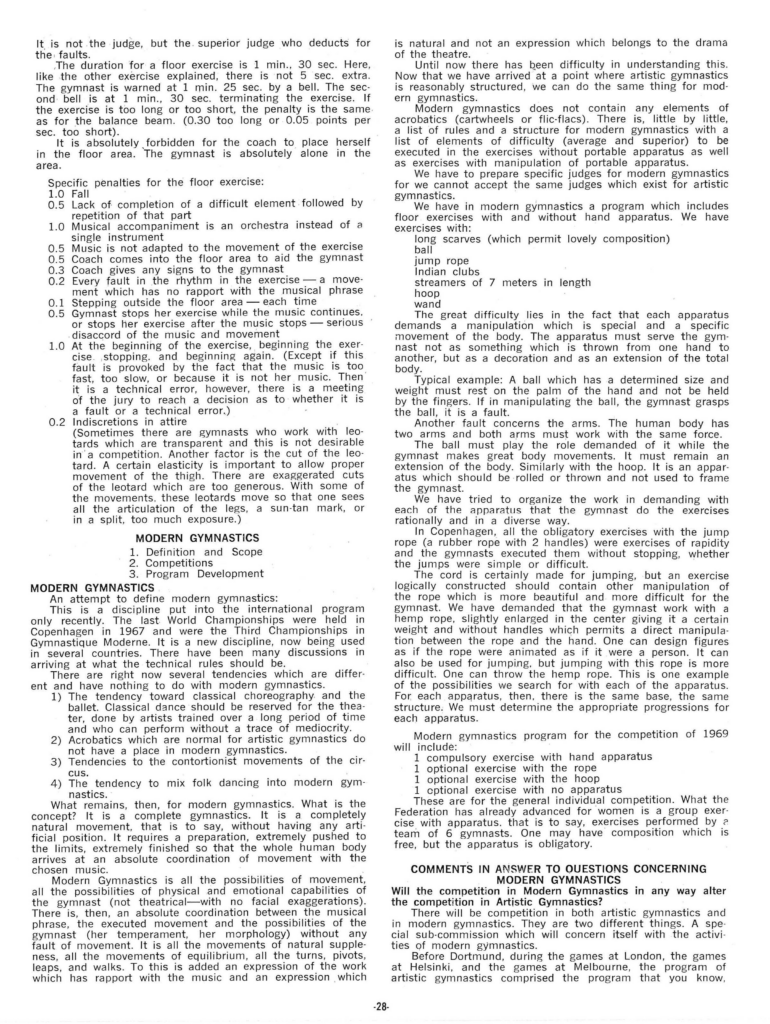

Should a gymnast look as though she were about to lose her family while she performs on floor?

No, gymnasts must express joy–not put on a theatrical drama:

Avoid in the composition physical expressions which are forced, that express the sentiment in the face. There should be body expression which expresses the musical phrase. If the musical phrase is serious, it is not necessary for the girl to look as though she were about to lose her family. The floor exercise, on the contrary, represents a joy, an expulsion, of the human body which expresses in all its possibilities what the musical phrase expresses. It is consequently a joy and not a theatrical drama.

Sadly, this attitude was common in the 1960s and would continue to plague the Women’s Technical Committee for decades to come.

Should your music fit your body type?

*Sigh* This one is a doozy:

If the gymnast is small, light, lively, dynamic, the music should be an image of that gymnast. If the gymnast is large and naturally has very large movements, the music should be more serious, but always employing variation of rhythm.

Note: I do not endorse this viewpoint.

What did the Code mean by indiscretions in attire?

Sometimes there are gymnasts who work with leotards which are transparent, and this is not desirable in a competition. Another factor is the cut of the leotard. A certain elasticity is important to allow proper movement of the thigh. There are exaggerated cuts of the leotard which are too generous. With some of the movements, these leotards move so that one sees all the articulation of the legs, a sun-tan mark, or in a split, too much exposure.

To Sum Things Up…

Female gymnasts couldn’t simply read the Code and expect to win. To compete in WAG in the 1960s meant learning all the unwritten rules, preferences, and expectations.

Appendix: Japanese Commentary on Ikeda’s Performance at the 1960 Olympics

After the 196o Olympics, Villancher called the Japanese gymnasts “imprudent” for assuming too much risk in their routines because it caused them to lose execution points. She singled out Ikeda as an example of this trend in routine composition.

That was Villancher’s explanation/rationalization for Ikeda’s scores. But the Japanese newspapers had a different interpretation. In 1960, the English-language newspaper Yomiuri made this observation:

Japan’s Keiko Ikeda, victim of some judging which drew jeers from the crowd, was in ninth place with 37.498 points and teammate Kiyoko Ono, wife of the men’s team captain, was tied for 12th with 37.1099 [sic].

The Japanese team protested the judging which gave Miss Ikeda only 9.266 points in her specialty, the balance beam, but when the judge was cautioned did not press the issue any further.

The Yomiuri, Sept. 8, 1960

Days later, it printed a blurb, which summarized an Italian newspaper article:

“Like Ship in Midst of Red Fleet”

Japan’s Keiko Ikeda was compared by a leading Italian newspaper Saturday to a battleship surrounded by the Russian fleet at Port Arthur.*

Commenting on the uproar raised by fans over the points given Mrs. Ikeda by the Soviet judge in the women’s Olympic gymnastics finals at the historic Baths of Caracalla,** the newspaper Il Messagero said: “Everything in gymnastics occurs with scrupulous obedience, the judges of the East raise the points of the Russian gymnasts and lower those of the Japanese.

“Keiko Ikeda, it seems, is like a battleship in the midst of the Russian fleet at Port Arthur.

“Keiko receives the biggest applause in the parallels and the beam but receives no better than fifth place from the judges. This causes whistling and cat calls sufficient to make Caracalla turn in his grave.

“As a reaction to all this, every Japanese girl receives tremendous applause. It seems they are all Keiko Ikeda.”

The Yomiuri, Sept. 11, 1960

In other words, the newspapers thought that Ikeda was the victim of unfair judging by the Soviet judges.

*The Battle of Port Arthur marked the commencement of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904.

**The 1960 gymnastics competition occurred outdoors, under a tarp, at the Baths of Caracalla.

Fast Forward

The amount of difficulty would be an ongoing debate in women’s artistic gymnastics. Normally, the history of excessive difficulty starts with Olga Korbut because the FIG considered banning her risky skills after the 1972 Olympics. From Modern Gymnast:

We have received many letters concerning the article pertaining to Olga Korbut, which is interesting since it is a direct result of the Women’s International Technical Committee meeting, January 21-30 at Stuttgart.

The meeting started off on this note: Beam: Too many acrobatics. The technicians should finally come to understand that acrobatics should be reserved for the floor exercise.

The exercise on the beam should include a minimum of acrobatics linked with balance positions, turns, rhythmic steps, etc.

Extensive acrobatics on the beam are not only prejudicial for the gymnasts but they also make the execution rather jerky with frequent pauses instead of the rhythmical continuity that is required.

This statement probably led to the action by the seven members of the Technical Committee which passed six to one with Mrs. Demidenko [of the Soviet Union] voting against the proposal which was as follows:

THE CLOSED SOMERSAULT ON THE BEAM

In view of the fact that this element is peculiar to the beam, the Women’s Technical Committee has decided to prohibit it. In this way, it is hoped to avoid danger for the gymnasts. This type of element can only be performed as a dismount.

In June in Stuttgart, the committee also decided to bar any movement on the uneven parallel bars that originates from the feet, such as Olga’s standing on the high bar and flipping to the same bar. This rule would also include her dismount.

Mr. Gander, according to the news article, says that there is nothing final concerning these decisions as they still must be approved by the Federation’s Assembly in Rotterdam next November.

Modern Gymnast, June/July 1973

The difficulty debate also popped up in 1995 regarding the Chinese gymnasts’ routines:

The world gymnastics governing body has condemned China’s new acrobatic technique as too dangerous.

But Chinese coach Lu Shanzen hit back at the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG) for being too cowardly over the sport’s development. “Without attempting to break new ground, gymnastics will lose its significance,” he said.

The Daily Yomiuri, Oct. 7, 1995

And the debate continues today with the valuation of Simone Biles’s skills, primarily her double-double dismount off beam and her Yurchenko double pike.

Ikeda: The Forgotten Innovator

Note: This is not meant to be a complete history of undervaluing difficulty. Rather, it is meant to serve as a reminder that we still have a lot to learn about the pre-Korbut and pre-Comăneci years of gymnastics.

Ikeda Keiko has been forgotten in the sport’s history as one of the early innovators who started the push for more difficulty — even before the Soviets did so.

More on Codes of Points

More on 1968