At the 1966 World Championships, the Czechoslovak women’s team finally defeated the Soviet team, and Čáslavská won the all-around title, defeating Kuchinskaya, who reportedly stated before the competition, “I will share the medals with Čáslavská!”

Stadión, a Czechoslovak sports magazine, dedicated several pages to the competition. The article’s tone was blunt in places. It criticized the complacency of the Czechoslovak men’s team, as well as the judges during the women’s event finals and Villancher’s interventions in the judging.

Note: Berthe Villancher, the President of the Women’s Technical Committee, was known for her interventions. For example, she intervened during Čáslavská’s beam routine at the 1968 Olympics and during Tourischeva’s beam routine at the 1969 European Championships.

It also provided interesting tidbits of information. For example, there were spies at the competitions in Czechoslovakia before the World Championships; the Czechoslovak pianist may have been the key to victory; and the Czechoslovak gymnasts’ shoes were believed to have magical powers.

Quick Links: Introduction | Men’s Competition | Women’s Competition | The Czechoslovak Pianist | The Last Minutes of the WAG Competition | Photo Captions | Miracle Shoes

Note: You can find the main articles on the 1966 World Championships here: men’s competition and women’s competition. You can read Čáslavská’s recollections of the competition here.

Introduction

2,854 Routines, 55 Hours

It’s really unbelievable. At the 16th World Artistic Gymnastics Championships, 2,854 compulsory and optional routines were performed. One hundred and forty-five men and one hundred and fifty-six women fought for the titles for a net fifty-five hours. A mammoth of an apparatus settled down in Dortmund’s Westfalenhalle. If one wanted to get a true picture of the overall state of world gymnastics, then one had no choice but to stay behind the barriers from morning until almost midnight. The situation demanded it, for the draw was such that in each of the many subdivisions either an excellent team or an outstanding individual competed. Well, there is nothing to regret, at least we can now dissect the mammoth.

[Note: There were complaints of judging fatigue at the 1966 World Championships.]

Stadión, October 5, 1966

2854 Sestav, 55 Hodin

Je to opravdu neuvěřitelné. Na šestnáctém mistrovství světa ve sportovní gymnastice byla zacvičeno 2854 povinných a volných sestav. Stotřiačtyřicet mužů a stošestapadesát žen bojovalo o tituly čistých pětapadesát hodin. V dortmundské Westfalenhalle se usadil mamut z nářadí. Chtěl-li si člověk udělat skutečně obraz o celkovém stavu světové gymnastiky, pak nezbývalo nic jiného než vydržet za bariérami od rána, téměř do půlnoci. Situace to vyžadovala, neboť vylosování bylo takové, že v každém z mnoha sledů startovalo buď výborné družstvo, či znamenitý jednotlivec. Nu, není čeho litovat, alespoň můžeme nyní mamuta rozpitvat.

The Men’s Competition

Men’s Gymnastics’ Quality Is Rising

This is how you could, in one sentence, define the parade of representatives of twenty-eight countries, among which only Romanians and Bulgarians were missing from the traditional gymnastics countries. For the sake of clarity we can divide the twenty-one complete six-member teams into several groups. The first group is small, made up of two gymnastic superpowers — Japan and the Soviet Union. Who will beat whom? How strongly will Soviet representatives press to take the lead to become the Olympic champions? This was a question that waited for an answer for practically two years and then was settled in two days. The Soviets included two veterans in the sextet, two former world champions, Boris Shakhlin and Yuri Titov. Boris Shakhlin was added even at the last minute, just before the start. What were they after? Titov and Shakhlin practically turned into rams breaking through the gate through which internationally unexperienced but excellent athletes were to enter the gymnastic paradise. There was no doubt that this was preparing the ground for the young team for the Olympic Games in Mexico. This was clear from the third routine on the first day of the compulsory routines, when the scores of the USSR and Japanese competitors began to intertwine. After completing all six disciplines, the Japanese led by almost two points, but Mikhail Voronin’s name appeared first and Sergei Diomidov’s third. Twenty-one-year-old Voronin was a perfect surprise. He even triumphed outright in the optional routines, winning by 90 hundredths of a point over Tsurumi with an overall score that no one has ever achieved at the World Championships: 116.15 points! Diomidov couldn’t hold his nerve and reached for the gold only on parallel bars, where he is the real champion. The Japanese team won overall by 4.25 points. The only partly disappointing performance was that of Olympic champion Endo, who had won all the qualifying competitions at home. Had he been in top form, he could have had a great contest with Voronin. The Japanese all proved to be excellent vaulters. Five of them appeared in the final battle and split the medals between them. Coach Takemoto (who did not lead the team) told reporters that he could have fielded two more such balanced teams and after Voronin’s victory added: In Mexico, this result will be enough for third place! Well, the voice of an expert must be taken seriously. What is certain is: the fight for Olympic medals in Mexico will still be a matter of the battle between the USSR and Japan. They will not let anyone take the gold and silver from them. But who will take the bronze? Dortmund has given a hint on that too.

Let’s take a look at the second group, who were hoping for the third position on the podium. According to the results between the Olympic Games and the World Championships, this group consisted of the teams of the German Democratic Republic [i.e. East Germany], Poland, Czechoslovakia, the USA, and the Federal Republic of Germany [i.e. West Germany]. They were joined by Finland. After the compulsory routines were over, there was no longer any doubt. The aspirant was the GDR sextet, whose best soloist was Matthias Brehme (23 years old). Brehme finished ninth in the overall individual classification. The others shared nineteenth to twenty-fourth place. It was a great success! After all, they practically beat us, as a team, by 9.80 pts, which is the difference of an entire class. Were we really that much worse in fourth place? We were. We got off to a great start. After completing the compulsory parallel bars and horizontal bar exercise, we were 1.5 points ahead of GDR! Then came a crisis. It is true that the judges supported us somewhat on floor, but we were not “riding the horse” during the pommel horse exercise. The rings also did not go as expected, and the fight with the judges on vault was futile. Interestingly, the team was not too critical of the performance after the compulsory routines and considered the three-point lead of the GDR already sufficient. Instead of getting ready to attack, it was preparing to maintain fourth place ahead of the Poles and the Americans. The team mobilized its forces only when it seemed that we would finish fifth. If it had fought the whole competition as it did at the end on the horizontal bar, then it would have deserved applause for its performance. Poland, which ranked fifth, relied on the Kubica brothers’ performances to finish 60 hundredths of a point behind us and two-tenths of a point ahead of the USA. The Americans had their traditional good optional routines and were getting high scores. Our second group ended with them. The third group in Dortmund consisted of the Yugoslavs, the West Germans, the Italians, and surprisingly the French. Yugoslavs = Cerar. He was the big figure of the championship and was only twenty-hundredths of a point away from third place in the all-around standings! Once again he performed excellently on pommel horse, parallel bars, and horizontal bar. All he had to do was get a better score on vault, and he was on the podium. Next to Cerar, young Kersnic (20 years old) is growing into a gymnast of great stature. Italy = Menichelli and Carminucci. Menichelli may have lost the luster of best man on floor exercise, but he amazed with excellent performances on parallel bars and rings. It seems that after the return of coach Günthard (he is to lead the Italian team again from the new year) Menichelli’s performance will go up even more. The Federal Republic of Germany’s team disappointed at home. The hall applauded the French all the more. Under the Japanese coach, the French are making up for what they missed. And there was a lot of it! The remaining group — starting from eleventh place in the standings — was diverse. The Finns were disappointing with the exception of Nissinen (19 years old) and Laiho (23 years old). Laiho fought his way to the final on pommel horse and that was also the only success of the former gymnastic superpower. The Hungarians remained far behind their capabilities. On the other hand, Cuba, where gymnastics was still in its infancy before the World Championships in Prague, was a pleasant surprise. Ramírez was nicknamed “the black Menichelli'” in Dortmund. Canada is working its way up, the work of coach Hrubý from Brno is also visible in the Austrians. Mexico has also embarked on a gymnastic journey. Under the guidance of the American Vega and with the cooperation of the Polish coach Jokiel, it did surprisingly well.

To conclude the chapter on the men, it is necessary to state that, on average, the exercises on horizontal bar (the combination of elements and the difficulty of the dismounts of the routines), on parallel bars and on floor exercise have improved. With the exception of the first three teams, rings still long for improvement, while vault and pommel horse in general should be improved by everyone except for the Japanese.

Úroveň mužské gymnastiky stoupá

Tak by se dala jednou větou definovat přehlídka reprezentantů osmadvaceti států, mezi nimiž chyběli z tradičních gymnastických zemí jen Rumuni a Bulhaři. Pro větší přehlednost si můžeme rozdělit jedenadvacet kompletních šestic do několika skupin. První skupina je malá, vytvořená ze dvou gymnastických velmocí — Japonska a Sovětského svazu. Kdo s koho? Jaký bude nápor sovětských reprezentantů na vedoucí místo olympijských vítězů? To byla otázka, na jejíž odpověď se čekalo prakticky dva roky a pak byla vyřízena ve dvou dnech. Sověti zařadili do sexteta dva veterány, dva bývalé mistry světa Borise Šachlina a Jurije Titova. Borise Šachlina dokonce na poslední chvíli, těsně před startem. Co tím sledovali? Titov i Šachlin se stali prakticky berany prorážejícími vrata, jimiž měli vstoupit do gymnastického ráje mezinárodně neostřílení, ale výborní borci. Nebylo pochyb, že se tím upravovala půda pro mladé mužstvo na olympijské hry v Mexiku. To bylo jasné od třetího nářadí při prvém dnu bojů v povinných sestavách, kdy se známky borců SSSR a Japonska začaly vzájemně prolínat. Po absolvování všech šesti disciplín vedli sice Japonci téměř o dva body, ale na prvním místě se objevilo jméno Michaila Voronina a na třetím Sergeje Diamidova. Jedenadvacetiletý Voronin byl dokonalým překvapením. Ve volných sestavách dokonce přímo triumfoval a zvítězil před Curumim o 90 setin bodu s celkovým výsledkem, který dosud na mistrovství světa nikdo nedocílil: 116,15 b.! Diamidov nevydržel nervově a sáhl po zlatu jen na bradlech, kde je skutečným mistrem. Japonské družstvo zvítězilo celkově o 4,25 b. Zaslouženě a přesvědčivě. Částečným zklamáním byl jen výkon olympijského vítěze Enda, který doma vyhrával všechny kvalifikační závody. Kdyby byl ve vrcholné formě, mohl svést s Voroninem velké klání. Japonci se ukázali všichni jako vynikající skokani. Pět se jich objevilo ve finálovém bojí a rozebrali si medaile mezi sebou. Trenér Takemoto (družstvo nevedl) prohlásil novinářům, že by mohl postavit ještě dva tak vyrovnané kolektivy a po Voroninově vítězství dodal: V Mexiku bude tento výsledek stačit sotva na třetí místo! Nu, hlas odborníka je nutné brát vážně. Jisté je: boj o olympijské medaile bude v Mexiku ještě záležitostí SSSR a Japonska. Zlato a stříbro si vzít nedají. Kdo však bude bronzový? I na to napověděl Dortmund.

Podívejme se proto na druhou skupinu, která si dělala naděje na třetí stupeň vítězů. Podle výsledků v rozmezí mezi OH a MS ji tvořila družstva Německé demokratické republiky, Polska, Československa, USA a Německé spolkové republiky. K ním ještě přistupovalo Finsko. Po skončení povinných sestav už nebylo pochyb. Aspirantem se stal sextet NDR, jehož nejlepším sólistou byl Matthias Brehme (23 let). V celkové klasifikaci jednotlivců skončil Brehme na devátém místě. Ostatní se podělili o devatenácté až čtyřiadvacáté místo. Byl to nesmírný úspěch! Vždyť nám prakticky utekli, jako družstvo, o 9.80 b., což je rozdíl třídy. Byli jsme opravdu na čtvrtém místě o tolik horší? Byli. Začátek našeho vystoupení byl výborný. Po absolvování povinného cvičení na bradlech a hrazdě jsme vedli nad NDR o 1,5 b! Pak přišla krize. Je pravda, že nás rozhodčí mírně přidrželi při prostných, ale na koni jsme „na koni“ nebyli. Kruhy rovněž nedopadly podle předpokladu a na přeskoku byl boj s rozhodčími marný. Je zajímavé, že družstvo nebylo k výkonu po povinných sestavách příliš kritické a tříbodový náskok NDR považovalo již za dostatečný. Místo k útoku se připravovalo na udržení čtvrtého místa před Poláky a Američany. Zmobilizovalo síly teprve ve chvíli, kdy už se zdálo, že skončíme pátí. Kdyby bojovalo celý závod jako v závěru na hrazdě, pak by zasloužilo za výkon potlesk. Páté v pořadí, Polsko, se opíralo o výkony bratří Kubiců a skončilo o 60 setin bodu za námi a o dvě desetiny bodu před USA. Američané měli tradičně dobrá volná cvičení a mohutně bodově dotahovali. Jimi také končí naše druhá skupina. Třetí tvořili v Dortmundu Jugoslávci, západní Němci, Italové a překvapivě Francouzi. Jugoslávci = Cerar. Ten byl velkou postavou mistrovství a od třetího místa v celkové klasifikaci ho dělilo jen dvacet setin bodu! Měl opět vynikajícího koně našíř, bradla a hrazdu. Stačilo přidat na přeskoku a stál na stupních vítězů. Vedle Cerara vyrůstá mladý Kersnic (20 let) v gymnastu velkého formátu. Itálie = Menichelli a Carminucci. Menichelli ztratil sice lesk nejlepšího muže v prostných, ale udivil výbornými výkony na bradlech a na kruzích. Zdá se, že po návratu trenéra Gündharda (má vést od nového roku opět italské družstvo) půdje Menichelliho výkon ještě nahoru. Družstvo NSR v domácím prostředí zklamalo. O to víc tleskala hala Francouzům. Pod vedením japonského trenéra dohánějí Francouzi to, co zameškali. A bylo toho hodně! Zbývající skupina — od jedenáctého místa v pořadí — byla různorodá. Zklamali Finové s výjimkou Nissinena (19 let) a Laiha (23 let). Laiho se probojoval do finále na koni našíř a to byl také jediný úspěch bývalé gymnastické velmoci. Daleko za svými možnostmi zůstali Maďaři. Naopak mile překvapila Kuba, kde byla před pražským mistrovstvím světa gymnastika ještě v plenkách. Ramifez dostal v Dortmundu přezdívku „černý Menichelli’“. Cestu vzhůru si klestí Kanada, práce trenéra doc. Hrubého z Brna je vidět i na Rakušanech. Na gymnastickou cestu se vydalo i Mexiko. Pod vedením Američana Vegy a za spolupráce polského trenéra Jokiela, vykročilo překvapivě dobře.

Závěrem kapitoly o mužích je nutné konstatovat, že v průměru se zlepšilo cvičení na hrazdě (kombinace prvků a obtížnost závěrů sestav), na bradlech a v prostných. S výjimkou prvních třech družstev čekají na vylepšení kruhy, s výjimkou Japonců přeskok a všeobecně kůň našíř.

The Women’s Competition

Long Unseen Duel of the Women

Predictions before the Women’s Gymnastics World Championships claimed that when two fight, the third one laughs. That is, that Japan or the GDR could emerge victorious from the USSR-Czechoslovakia duel. This time the predictions failed. Although the Japanese women were close behind the two leading teams in the compulsory routines, they were no longer able to keep up during the optional routines. The GDR team disappointed with their performance, and only Zuchold saved their reputation. That’s just for the record.

The whole gymnastics world focused on two teams that fought an unprecedented battle for the world championship. Since the World Championships in Prague, it was known that our team wanted to attack the Soviet Union’s dominance. In Tokyo, our team succeeded in the women’s individual competition, in Dortmund the team was to take the gold. All over the world, journalists were writing about Czechoslovakia’s preparation, and there were gymnastic spies at almost every competition in our country. This led to many new elements remaining under wraps for a long time. But one thing was certain: Czechoslovak gymnasts arrived at the World Championships in excellent condition. It was also known that, in the Soviet Union, the youngsters had come to the forefront, that the seventeen-year-old girls had come to the fore. A new name, Kuchinskaya, was added to Petrik. “I will share the medals with Čáslavská!” This phrase appeared on the pages of many magazines, and Kuchinskaya was at the center of attention. Is this hyperbole or healthy confidence? Seventeen years — the world belongs to me. The scores from the qualifying competitions showed that Kuchinskaya would indeed be one of the top gymnasts. But the top must rely on the heel. At the World Championships, Astakhova and Latynina were Kuchinskaya’s heel. Latynina, the world champion from Prague, has become a springboard for young hope. A world champion rarely gets a low score, and the one who competes after her must be a star indeed. The score therefore goes up. That must have been expected. Kuchinskaya appeared in the overall ranking after the compulsory routines really close behind the leader, Čáslavská. The Soviet Union’s team led ours by 363 thousandths of a point.

There is only one interpretation of the compulsory routines for excellent gymnasts, both men and women. To perform them in the best way, that is, to the extreme positions and in full perfect range. That’s what our whole team did, including Čáslavská. According to the experts, the difference between Čáslavská and Kuchinskaya would have to be at least half a point. That alone would be enough for the team to lead. This finding cost Čáslavská a lot of nerves. The fact that she overcame this crisis, and, if the whole team coped with it, is a testimony to her immense fighting spirit and confidence in herself. After all, after the optional routines performed by the Soviet team before ours, the chances of winning both titles were really low. Čáslavská had to go through the competition — if she wanted to win — with an average score of over 9.80 points. What seemed impossible became a reality. It was a fantastic performance by all six girls and the coach.

[Reminder: There weren’t team and all-around finals at the time. So, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union did not compete at the same time, and neither did Čáslavská and Kuchinskaya.]

The performance of the Soviet team, which for Mexico will be based on the quartet of Kuchinskaya, Petrik, Druzhinina [later Voronina], and Kharlova [later Karaseva or Karasova], was excellent. These girls are practically at the beginning of their gymnastic careers, and their performances will understandably grow. They definitely have enough healthy ambition.

The remaining teams stayed in the shadow of the duel between the top two teams. It was as if the compulsory routines had already been decisive for all of them. The order of the top five places was quite clear and if there is a knife fight to be written about, then perhaps only between the teams of the USA, France, and Bulgaria. The home athletes were completely defeated, and Polish women played second fiddle. The point difference between the first — Czechoslovakia and the last — Austria is a full 53 points. This speaks for itself. The level has moved up in the world overall on floor and uneven bars. For many, balance beam is still a vicious piece of wood to fall from, and vault remains a weakness.

A Word on the FIG

What cannot be measured in goals, meters, and seconds is hard to judge, they say in the sports world. That’s why judges in all sports where scoring matters are not popular. And yet, standards are set for judges, regular training sessions are conducted for judges before the World Cup, and they are also tested. It is certainly no mean feat to sit and judge performances for almost twelve hours a day. That, in itself, is a great mental strain, and mistakes can happen because the judges are human. However, the situation is different in the final matches. Here, no one can make excuses for fatigue; here the judges evaluate only six sets. If the male judges in the final competitions handled the task almost 100%, the same cannot be said about the female judges. The chairwoman of the FIG Women’s Technical Commission, Mrs. Villancher, played, to put it mildly, an embarrassing role, from running around individual judges to the announcement of the results. One has to ask the question how is it possible that we are not represented in the women’s commission at all? Isn’t it quite an absurd phenomenon that one of the oldest members of the FIG, which Czechoslovakia certainly is, has minimal representation in this organization? After the results achieved in Dortmund, there is no doubt that we can also count ourselves among the world’s gymnastic elite. And such elite must have the right to be represented!

Dlouho nevídaný souboj žen

Prognózy před mistrovstvím světa v gymnastice žen tvrdily, že když se dva perou, třetí se směje. Tedy, že ze souboje SSSR-ČSSK může vyjít vítězně Japonsko nebo NDR. Prognózy tentokrát zklamaly. Japonky se sice v povinných sestavách držely těsně v závěsu za oběma vedoucími družstvy, ale ve volných sestavách přece jen už nestačily. Družstvo NDR svým výkonem zklamalo a čest zachraňovala pouze Zucholdová. To jen na okraj.

Celý gymnastický svět upřel pozornost na dvě družstva, která spolu svedla dlouho nevídaný boj o světové prvenství. Již od pražského MS bylo známo, že naše družstvo chce zaútočit na prioritu Sovětského svazu. V Tokiu se to podařilo v soutěži jednotlivkyň, v Dortmundu měl zlato převzít i celek. O přípravě Československá se psalo v celém světě a téměř na každém závodě u nás byli gymnastičtí špehové. Vedlo to k tomu; že mnoho nových prvků zůstalo dlouho pod pokličkou. Jisté však bylo: československé gymnastky přijely na mistrovství světa ve vynikající kondici. Vědělo se rovněž, že v Sovětském svazu napnuli plachty mládi, že ke slovu se dostala sedmnáctiletá děvčata. K Petrikové se přidalo nové jméno Kučinská. „Podělím se s Čáslavskou o medaile!” Tato věta se vynořila na stránkách mnoha časopisů a Kučinská se stala středem zájmu. Je to nadsázka, nebo zdravá sebedůvěra? Sedmnáct let — patří mi svět. Bodové hodnocení z kvalifikačních závodů ukazovalo, že Kučinská bude opravdu patřit mezi gymnastickou špičku. Špička však musí spoléhat i na patu. Kučinské na mistrovství světa dělaly patu Astachovová s Latyninovou. Mistryně světa z Prahy Latyninová se stala odrazovým můstkem mladé naděje. Mistryně světa těžko dostává nízkou známku a ta, která cvičí až za ní, musí být skutečně hvězda. Známka s bodovým výsledkem proto stoupá. S tím se muselo počítat. Kučinská se objevila v celkovém pořadí po povinných sestavách skutečně v těsném závěsu za vedoucí Čáslavskou. Družstvo Sovětského svazu vedlo nad naším o 363 tisíciny bodu.

Je jen jediný výklad povinných sestav pro vynikající gymnasty i gymnastky. Zacvičit je nejlépe, tedy až do krajních poloh a v plném perfektním rozsahu. To dělalo celé naše družstvo, tak cvičila tedy i Čáslavská. Podle expertů by rozdíl mezi Čáslavskou a Kučinskou musel být nejméně půl bodu. To by samo o sobě stačilo i k vedoucí pozici družstva. Toto zjištění stálo Čáslavskou hodně nervů. Překonala-li tuto krizi a vyrovnalo-li se s ní i celé družstvo, svědčí to o nesmírné bojovnosti a důvěře v sama sebe. Vždyť po volných sestavách, které cvičilo sovětské družstvo před naším, vyhlížela naděje na oba tituly skutečně minimálně. Čáslavská musela projít závodem — chtěla-li zvítězit — s průměrnu známkou nad 9,80 bodu. Co se zdálo nemožným, stalo se skutkem. Byl to fantastický výkon všech šesti děvčat i trenérky.

Výkon sovětského družstva, jehož základem také pro Mexiko rozhodně bude kvartet Kučinská, Petriková, Družininová a Charlovová, byl vynikající. Tato děvčata jsou prakticky na začátku gymnastické dráhy a jejich výkony pochopitelně porostou. Zdravé ctižádosti mají rozhodně dost.

Ve stínu duelu dvou prvních zůstávala ostatní družstva. Jako by u všech rozhodly už povinné sestavy. Pořadí na pěti prvních místech bylo zcela jasné a pokud se dá psát o dalším boji na nůž, tak snad jen mezi celky USA, Francie a Bulharska. Zcela propadly domácí závodnice, druhé housle hrály i Polky. Bodový rozdíl mezi prvním — Československem a posledním — Rakouskem je plných 53 bodů. To hovoří samo o sobě. Úroveň se posunula ve světovém celku u prostných a na bradlech. Kladina je pro mnohé stále ještě začarovaným kusem dřeva, z kterého se padá a přeskok zůstává nadále slabinou.

Slovo k FIG

Co není na góly, na metry a na vteřiny se dá těžko posuzovat, říká se v národě sportovců. Proto rozhodčí ve všech sportech, v nichž záleží na bodování, nejsou oblíbení. A přece i pro rozhodčí jsou stanoveny normy, pro rozhodčí se dělají před mistrovstvím světa pravidelná školení a jsou také zkoušení. Není rozhodně žádný med sedět a posuzovat výkony téměř dvanáct hodin denně. To samo o sobě je velkým duševním vypětím a k omylům může dojít, protože rozhodčí jsou lidé. Jiná situace však nastává ve finálových střetnutích. Tady se na únavu nemůže nikdo vymlouvat, tady posuzuje rozhodčí jen šest sestav. Zvládli-li muži-rozhodčí ve finálových závodech úlohu téměř stoprocentně, pak o ženských sudích se to říci nedá. Předsedkyně technické komise žen FIG, paní Willancherová sehrála, mírně řečeno, trapnou roli, od obíhání jednotlivých rozhodčích až po vyhlášení výsledků. Stojí za zamyšlení, jak je možné, že nemáme v komisi žen vůbec zastoupení? Není dost absurdním úkazem, že jeden z nejstarších členů FIG, jímž ČSSR rozhodně je, má v této organizaci minimální zastoupení? Po výsledcích dosažených v Dortmundu není sporu o tom, že se i my můžeme počítat mezi světovou gymnastickou elitu. A ta přece musí mít na to Právo!

Call-out Box on Rudolf Kyznar, the Pianist

In the moment of greatest joy over the world championship title, Dáda Sedláčková called, “Girls, where is Ruda?” And then that sentence went around the corridors among our tourists. “Where’s Ruda?” Rudolf Kyznar stood outside the hall, his eternal humor gone. He was experiencing joy himself, so great and quiet as he told me later. “No way; I wasn’t thinking about the music at all, I wasn’t thinking about how many times I’d played “Vltava” and how long I’d shortened “Šárka.” I was just happy that those hundreds of hours in practice had paid off for the girls!” He didn’t escape the ovation anyway. Yuri Titov also shook his hand: “You won your team an extra half point! You should get a gold medal for piano! “Finally, he was the best pianist at the championship. The Swiss and the Spanish came to him just to play for them. The English even gave up their recorded tapes and Kyznar improvised.

Note: Čáslavská tells a humorous story about Kyznar in her autobiography.

V okamžiku největší radosti nad získaným titulem mistryň světa zavolala Dáda Sedláčková: „Žáby, kde je Ruda?““ A pak se ta věta rozletěla po ochozech mezi našimi turisty. „Kde je Ruda?““ Rudolf Kyznar stál venku před halou a jeho věčný humor byl pryč. Prožíval si radost sám, takovou velkou a tichou jak mi později říkal. „Kdepak; vůbec jsem nemyslel na muziku, vůbec jsem nemyslel, kolikrát jsem hrál Vltavu a jak dlouho jsem zkracoval Šárku. Já měl jen radost, že ty stovky hodin v tréninku se děvčatům vyplatily!“ Ovacím-však stejně neušel. Ruku mu stiskl i Jurij Titov: „Půl bodu navíc si vašim uhrál ty! Měl bys dostat zlatou za klavír!“ Konečně, byl to nejlepší klavírista na mistrovství. Vždyť za ním přišly Švýcarky, Španělky, jen aby jim hrál. Angličanky se dokonce vzdaly magnetofonových ů a Kyznar improvizoval.

Call-out Box on the Last Minutes of the Women’s Competition

Last Minutes

Suddenly the floor exercise was here, and the point difference between our team and the Soviet team was minimal. Six girls in blue leotards marched to the vault with a resolution: now or never! In the corridors, journalists worked as counters and almost all the tourists did the same. If the judges had put on… If Marika had mastered the hecht. She’s the only one vaulting it in Dortmund… If Dada had stuck… And to top it all off: “Věra only needs 9.7, and she’s world champion!”

The Czech-speaking crowds, scattered around the hall, began to converge on a small piece of the exposed cycle track right in front of the apparatuses. Who was more nervous? The girls under the podium, or those who were holding their thumbs? Cigarettes were being lit. It’s not supposed to happen, but who can stand it?

The first vaults, the first mass shouts: you must stick! Then the applause. The girls were hanging on the judges with their eyes. How did Marika Krajčířová vault?

Okay, great! Final score! Again applause and then a voice: “Gee, if Věra vaults to 9.7, not only will she win, but the team will be first! ” – “It’s true, I counted it too! Do the TV people know? It’s on the air. Someone jump up, there’s Pek! Tell him to say it!”

Nobody jumped up, Věra was vaulting “Věra-style!” There was silence behind the usual: stand still. How many points will they give her?

The score for the first vault: 9.7!

A hurricane blew through the hall. We won, we won everything! We have all the world champions.

The second vault has not been seen by many, because everyone had tears in their eyes. It didn’t even matter anymore. For half a minute the girls were already world champions!

Poslední minuty

Najednou tu byla volná prostná a bodový rozdíl mezi našim a sovětským družstvem byl minimální. K přeskoku pochodovalo šest děvčat v modrých trikotech s předsevzetím: teď anebo nikdy! V ochozech pracovali novináři v roli počtářů a totéž dělali téměř všichni turisté. Kdyby rozhodčí nasadili… Kdyby Marika vypálila letku. Skáče ji přece jediná ze všech závodnic v Dortmundu… Kdyby Dáda zapíchla… A do toho všeho: „Věře stačí 9,7 a je mistryně světa!“

Hloučky mluvící česky, rozházené po hale, se: začaly slévat na malém kousku obnažené cyklistické dráhy přímo před nářadím. Kdo byl víc nervózní? Děvčata pod pódiem, nebo ti, kteří drželi palce? Zapalovaly se cigarety. Nemá se to, ale kdo to má vydržet?

První skoky, první hromadné výkřiky: musíš a stůj! Potom hned potlesk. Děvčata visela očima na rozhodčích. Jak skočila Marika Krajčírová?

Dobře, výborně! Výsledná známka! Znovu potlesk a pak hned hlas: „Jéžišmarjá, jestli skočí Věra na 9,7 tak nejen, že vyhraje, ale družstvo bude první!“ — „Je to pravda, já to taky spočítal! Vědí to televizáci? Vždyť se vysílá. Skočte někdo nahoru, je tam Pek! Ať to řekne!“

Nikdo nahoru neskočil, Věrka skákala „věrku“! Za obvyklým: stůj bylo pojednou ticho. Kolik jí dají?

Známka za první přeskok: 9,7!

Halou proletěl uragán. Vyhráli jsme, vyhráli jsme všechno! Máme všechny mistryně světa.

Druhý skok už mnozí pro vodový film v očích neviděli. Už na něm ani nezáleželo. Už půl minuty byla děvčata mistryně světa!

Photo Captions

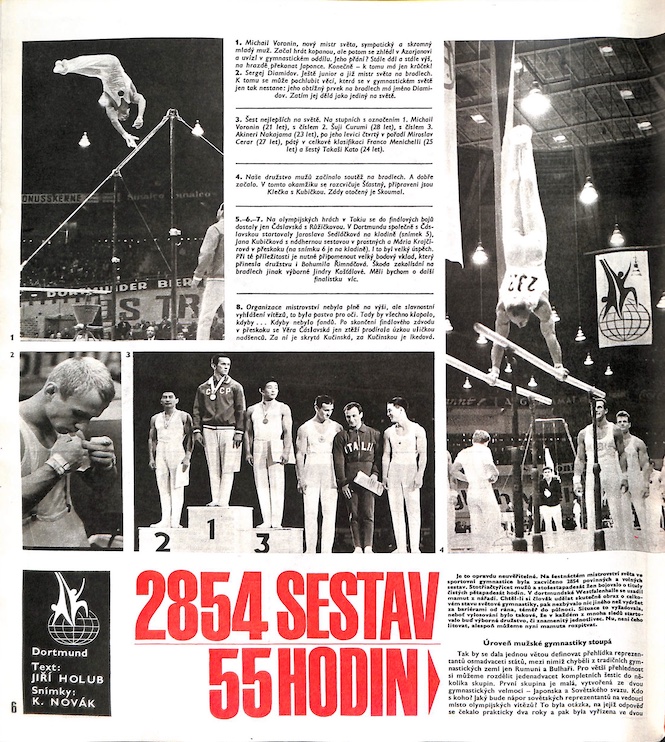

1. Mikhail Voronin, the new world champion, a likeable and modest young man. He started out playing soccer, but then he saw Azaryan and got stuck in the gymnastics club. His wish? To keep going higher and higher, to beat the Japanese on horizontal bar. Finally — he’s one step closer!

2. Sergei Diomidov. Still a junior and already world champion on parallel bars. In addition, he can boast of something that doesn’t just happen in the gymnastics world: his difficult element on the parallel bars has the name Diomidov. He’s the only one in the world to do it so far.

3. The six best in the world. On the podium with the number 1. Mikhail Voronin (21 years old), with the number 2. Tsurumi Shuji (28 years old), with the number 3. Nakayama Akinori (23 years old), with Miroslav Cerar (27 years old) fourth on his left, Franco Menichelli (25 years old) fifth overall, and Kato Takashi (24 years old) sixth.

4. Our men’s team started the competition on parallel bars. And it started well. At this point, Šťastný is warming up, Klečka and Kubička are ready. With his back turned is Skoumal.

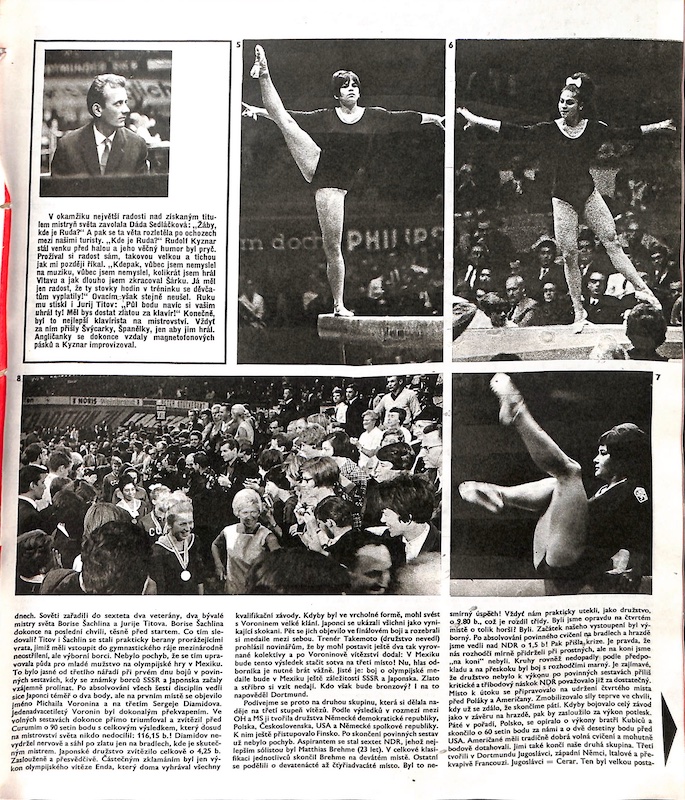

5.-6.-7. At the Tokyo Olympics, only Čáslavská and Růžičková made it to the finals. In Dortmund Jaroslava Sedláčková on beam (picture 5) competed together with Čáslavská, Jana Kubičková with a beautiful routine on the uneven bars and Mária Krajčírová on the vault (she is on beam in picture 6). This was also a great success. On this occasion, it is necessary to mention the great point contribution that Bohumila Řimnáčová brought to the team. It is a pity that the otherwise excellent Jindra Košt’álová faltered on the uneven bars. We would have had one more finalist.

8. The organization of the championship was not fully up to par, but the award ceremony was a feast for the eyes. Everything would have been fine here if… If it wasn’t for the fans. At the end of the final competition on vault, Věra Čáslavská could hardly make her way through the narrow aisle of enthusiasts. Behind her is Kuchinskaya, and behind Kuchinskaya is Ikeda.

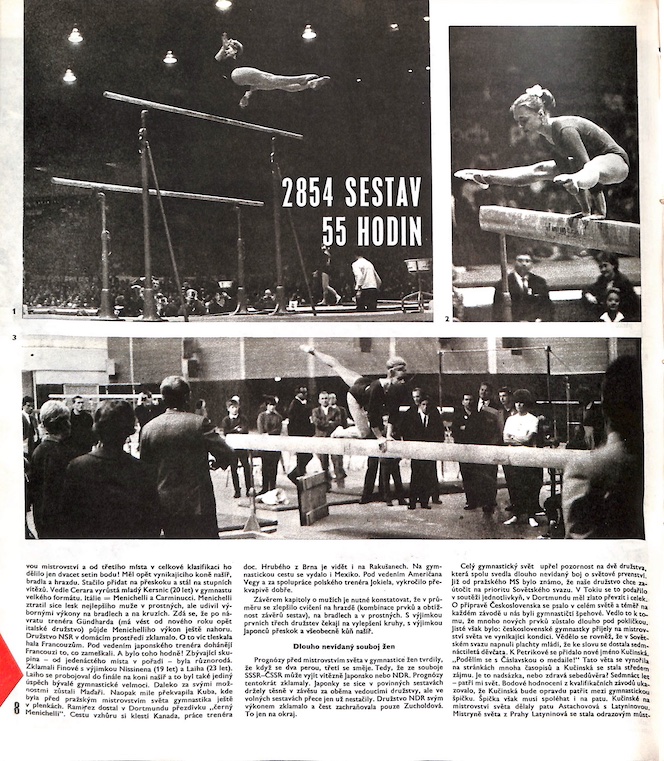

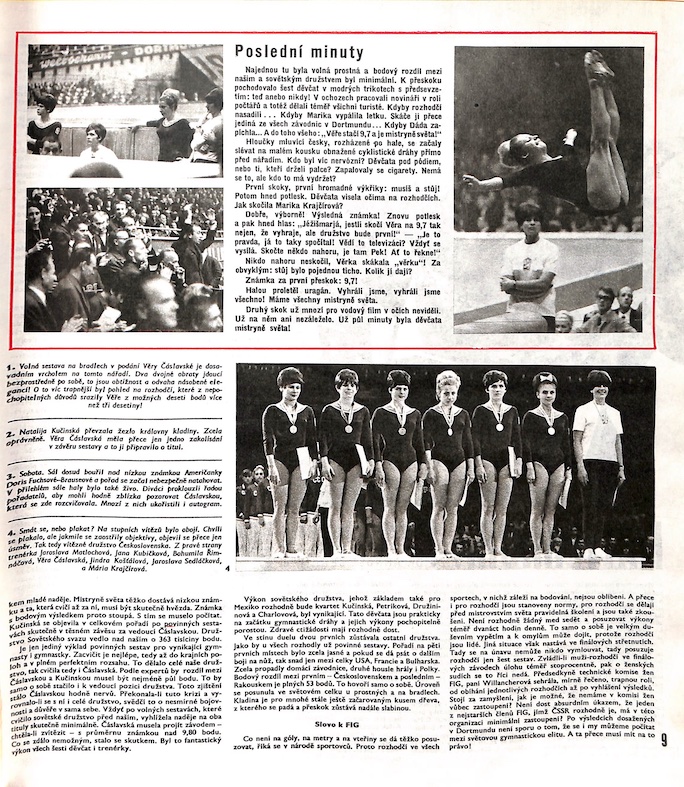

1. Optional routine on uneven bars performed by Vera Čáslavská is the best on this apparatus so far. Two turns in immediate succession, that’s difficulty and courage multiplied by elegance! All the more embarrassing was the sight of the judges, who for some incomprehensible reasons knocked more than three-tenths off Věra’s possible ten points!

2. Natalia Kuchinskaya took the scepter of the queen of the balance beam. Rightfully so. Věra Čáslavská had just one wobble at the end of the routine, and it took her title away.

3. Saturday. The hall was still in an uproar over the low score of the American Doris Fuchs-Brause, and the program began to stretch dangerously long. The adjoining hall was also lively. Spectators slipped through the line of organizers to get a very close look at Čáslavská, who was warming up. Many of them even got her autograph.

4. To laugh or to cry? There were both on the podium. There was crying for a while, but as soon as the lenses came into focus, there was a smile after all. So, the winning team of Czechoslovakia. From the right side coach Jaroslava Matlochová, Jana Kubičková, Bohumila Řimnáčová, Věra Čáslavská, Jindra Košt’álová, Jaroslava Sedláčková, and Mária Krajčírová.

1. Michail Voronin, nový mistr světa, sympatický a skromný mladý muž. Začal hrát kopanou, ale potom se zhlédl v Azarjanoví a uvízl v gymnastickém oddílu. Jeho přání? Stále dál a stále výš, na hrazdě překonat Japonce. Konečně — k tomu má jen krůček!

2. Sergej Diamidov. Ještě junior a již mistr světa na bradlech. K tomu se může pochlubit věcí, která se v gymnastickém světě jen tak nestane: jeho obtížný prvek na bradlech má jméno Diamidov. Zatím jej dělá jako jediný na světě.

3. Šest nejlepších na světě. Na stupních s označením 1. Michail Voronin (21 let), s číslem 2. Šuji Curumi (28 let), s číslem 3. Akinori Nakajama (23 let), po jeho levici čtvrtý v pořadí Miroslav Cerar (27 let), pátý v celkové klasifikaci Franco Menichelli (25 let) a šestý Takaši Kato (24 let).

4. Naše družstvo mužů začínalo soutěž na bradlech. A dobře začalo. V tomto okamžiku se rozcvičuje Šťastný, připraveni jsou Klečka s Kubičkou. Zády otočený je Skoumal.

5.–6.–7. Na olympijských hrách v Tokiu se do finálových bojů dostaly jen Čáslavská s Růžičkovou. V Dortmundu společně s Čáslavskou startovaly Jaroslava Sedláčková na kladině (snímek 5), Jana Kubičková s nádhernou sestavou v prostných a Mária Krajčírová v přeskoku (na snímku 6 je na kladině). I to byl velký úspěch. Při té příležitosti je nutné připomenout velký bodový vklad, který přinesla družstvu i Bohumila Řimnáčová. Škoda zakolísání na bradlech jinak výborné Jindry Košťálové. Měli bychom o další finalistku víc.

8. Organizace mistrovství nebyla plně na výši, ale slavnostní vyhlášení vítězů, to byla pastva pro oči. Tady by všechno klapalo, kdyby… Kdyby nebylo fandů. Po skončení finálového závodu v přeskoku se Věra Čáslavská jen ztěží prodírala úzkou uličkou nadšenců. Za ní je skrytá Kučinská, za Kučinskou je Ikedová.

1. Volná sestava na bradlech v podání Věry Čáslavské je dosavadním vrcholem na tomto nářadí. Dva dvojné obraty jdoucí bezprostředně po sobě, to jsou obtížnost a odvaha násobené elegancí! O to víc trapnější byl pohled na rozhodčí, které z nepochopitelných důvodů srazily Věře z možných deseti bodů více než tři desetiny!

2. Natalija Kučinská převzala žezlo královny kladiny. Zcela oprávněně. Věra Čáslavská měla přece jen jedno zakolísání v závěru sestavy a to ji připravilo o titul.

3. Sobota. Sál dosud bouřil nad nízkou známkou Američanky Doris Fuchsové—Brauseové a pořad se začal nebezpečně natahovat. V přilehlém sále haly bylo také živo. Diváci proklouzli řadou pořadatelů, aby mohli hodně zblízka pozorovat Čáslavskou, která se zde rozcvičovala. Mnozí z nich ukořistili i autogram.

4. Smát se, nebo plakat? Na stupních vítězů bylo obojí. Chvíli se plakalo, ale jakmile se zaostřily objektivy, objevil se přece jen úsměz. Tak tedy vítězné družstvo Československa. Z pravé strany trenérka Jaroslava Matlochová, Jana Kubičková, Bohumila Řimnáčová, Věra Čáslavská, Jindra Košťálová, Jaroslava Sedláčková, a Mária Krajčírová.

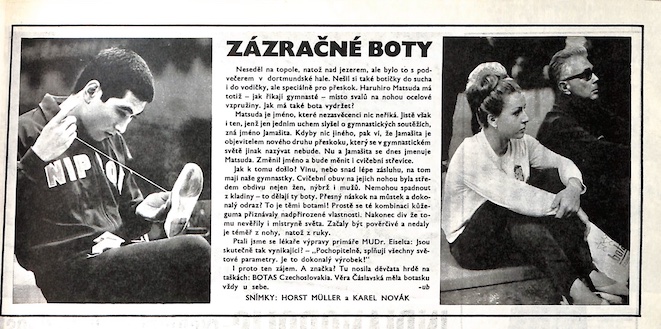

MIRACLE SHOES

He wasn’t sitting on a poplar tree, let alone over a lake, but it was with an early evening in a Dortmund hall. He also didn’t sew boots for dry weather or water, but specifically for the vault. For Haruhiro Matsuda has — as gymnasts say — steel springs instead of muscles in his legs. How is the shoe supposed to last?Matsuda is a name that means nothing to the uninitiated. But surely even someone who has only heard of gymnastic competitions with one ear knows the name Yamashita. If nothing else, he knows that Yamashita is the discoverer of a new kind of vault that will have no other name in the gymnastic world. Well, Yamashita’s name today is Matsuda. He’s changed his name, and he’s going to change his training shoes.

How did this happen? The blame, or perhaps better, the credit, lies with our gymnasts. The exercise shoes on their feet were the center of admiration not only of women but also of men. They can’t fall off the balance beam – the shoes do that. A precise leap onto the vault and a perfect bounce? That’s the shoes! There were simply supernatural properties attributed to that combination of leather and rubber. In the end, it’s a wonder even the world champions didn’t believe it. They became superstitious and wouldn’t let them off their feet, let alone their hands.

We asked the expedition’s physician, Dr. Eiselt: are they really that excellent? — “Of course, they meet all the global parameters. It’s a perfect product!”

That’s where the interest comes from. And the brand? The girls wore it proudly on their bags: BOTAS Czechoslovakia. Věra Čáslavská always had her Botas shoes with her.

Stadión, Oct. 12, 1966

ZÁZRAČNÉ BOTY

12. října 1966

Neseděl na topole, natož nad jezerem, ale bylo to s podvečerem v dortmundské hale. Nešil sí také botičky do sucha i do vodičky, ale speciálně pro přeskok. Haruhiro Matsuda má totiž — jak říkají gymnasté — místo svalů na nohou ocelové vzpružiny. Jak má také bota vydržet?

Matsuda je jméno, které nezasvěcencí nic neříká. Jistě však i ten, jenž jen jedním uchem slyšel o gymnastických soutěžích, zná jméno Jamašita. Kdyby nic jiného, pak ví, že Jamašita je objevitelem nového druhu přeskoku, který se v gymnaástickém světě jinak nazývat nebude. Nu a Jamašita se dnes jmenuje Matsuda. Změnil jméno a bude měnit i cvičební střevíce.

Jak k tomu došlo? Vinu, nebo snad lépe zásluhu, na tom mají naše gymnastky. Cvičební obuv na jejich nohou byla středem obdivu nejen žen, nýbrž i mužů. Nemohou spadnout z kladiny — to dělají ty boty. Přesný náskok na můstek a dokonalý odraz? To je těmi botami! Prostě se té kombinaci kůžeguma přiznávaly nadpřirozené vlastnosti. Nakonec div že tomu nevěřily i mistryně světa. Začaly být pověrčivé a nedaly je téměř z nohy, natož z ruky.

Ptali jsme se lékaře výpravy primáře MUDr. Eiselta: jsou skutečně tak vynikající? — „Pochopitelně, splňují všechny světové parametry. Je to dokonalý výrobek!“

I proto ten zájem. A značka? Tu nosila děvčata hrdě na taškách: BOTAS Czechoslovakia. Věra Čáslavská měla botasku vždy u sebe.