After Čáslavská’s disappointment in her performance in Dortmund, she debated if she should take a break from competing. Perhaps she had become too familiar to the judges, one coach suggested. (At one point in this section, Čáslavská recalls how the overly familiar Latynina was ignored during a press conference with Larisa Petrik in 1965.)

To make gymnastics exciting again, she and her coach Matlochová reworked all her routines, adding new elements to every routine. They made practice fun, with Matlochová riding a broom and trying to distract Čáslavská during her beam routines. They set her routines and training cues to music.

Čáslavská went on to compete at the 1967 European Championships. But Čáslavská had her doubts at the beginning of the competition. After a rough bar routine during the first rotation and an exceptional performance by Kuchinskaya on beam, Čáslavská was unsure if she would be able to defend her title. But right before beam, one of her superstitions happened. Someone broke a glass, and she had her lucky shards of glass.

In the end, she became the only gymnast in the history of the European Championships to sweep all five events twice. She even scored two perfect 10.0s during the event finals.

Another interesting tidbit: For someone who ended up on top of the podium many times, Čáslavská disliked being on top of the podium. It made her feel awkward.

So, with no further ado, here’s how Čáslavská recalls the 1967 European Championships in her autobiography from 1972.

Note: You can read more about the 1967 European Championships here and here.

Ten from the Land of Tulips— Amsterdam 1967

In a few moments, festive fanfare will be heard, and the 1967 European Championship will begin. We are standing in the next hall, there are exactly forty-two of us, all of us festively combed and groomed. We are also pretty — or so we think, like all women.

Excitement and confusion intensify; nervousness descends on us like an English fog and settles on each one. The contestants are nervous; the organizers are nervous; everyone is nervous. Coaches are always the most nervous of all. The real torment begins for them during the competitions, because they know the weaknesses of their wards, tricky places, and pitfalls, they simply know best of all where the Achilles heel is. At the same time, they cannot intervene or help in any way, they only have to look on helplessly. Once, coach Matlochová admitted that all her muscles hurt after the competitions because she mentally performs with us. Slávka knows my routine down to the smallest detail, she knows when I do a certain element that I have half-won, but that I can still fail here and there. In Tokyo, when Hanka Růžičková was performing on balance beam, Slávka Matlochová closed her eyes and had someone else comment on her routine.

The start of the opening ceremony is delayed for unknown reasons — someone gave the order to spread out. Like a bag of fleas bursting open, all the competitors start jumping, running, bending over, more upside down and feet up than the other way around, all excited and agitated again. In addition, a lot of female chatter, just confusion like in a panopticon.

I also have to run and get up to speed. I ran across the hall… But I am not running alone, my Dortmund shadow, Natasha Kuchinskaya, is accompanying me. She exudes great self-confidence. I accidentally crouched down…

*

When Yugoslav Miroslav Cerar jogs just before the start, he deliberately runs in the opposite direction of his opponents, wanting to see their faces. A lot can be learned from it. He looks cheerful himself, as if nothing is going on, and thus quite often disorients the opponent. Eva Bosáková locked herself in the dressing room and waited for the coach to hoist her directly on the balance beam, Larisa Latynina looked oblivious, almost indifferent to her surroundings, Tanaka Keiko sang to herself before the competition. Natasha Kuchinskaya impresses her opponents with a challenging, self-confident demeanor.

From many, many competitions, I have verified that almost everyone masks their own true feelings that they are experiencing. The one who scares the most usually has the most fear, and not everyone who sings is into singing. I will confess, and this is the first time out loud, that before each of my competitions I experienced a terrible torment of fear; at every competition, I literally passed out.

[Reminder: She has had stage fright since she was young.]

The pre-start fever manifests itself in me in such a way that I literally shake, my voice even shakes. Most of the time, I’m incredibly quiet, I answer in a monosyllabic, impenetrable manner. No one would give me a penny. Every time, before I get on the apparatus, I have to shake off all these feelings — otherwise, I absolutely couldn’t stand it. I remember a public training session in Kiel. It was very important to me to keep my name and prestige in front of the new Soviet hopes. Larisa Petrik and the young and clever Tourischeva were there at the time. They came to the hall a little earlier and started to gain an audience by dancing together. When I entered the hall and felt the atmosphere, I preferred to curl up into a ball, and there, I slouched in place and wished that the training was over. My coach was very upset at the time. She came to me, and so that no one could see her indignation, she said through her teeth, “Please, are you normal? Put your foot here!” and she tried to pull it not up to my nose, as is usual, but up to my ears. At that moment, I was like a wooden doll with legs on rubber bands and could spin them around all the time.

Be that as it may, it made a noise in the audience, the attention was focused on me, and I started to be in my skin again.

*

An announcer sounded from the main hall, then a buzzer sounded, the command to march sounded, and all I could think about was not to accidentally step on my left foot. I’m not normally superstitious, but once I’m in a competitive environment, I’m done. I have a lot to do right away to satisfy all the superstitions that “help” me during the competitions. Oh man, I’m making this up. Immediately this and immediately that. Most of all, I hold on to the shards. They are said to bring good luck. I have been a firm believer in this for some time. In 1962, before the women’s national championship, someone broke a glass. I just put one shard in the bag in which I carry my training shoes. And I became the national champion for the first time. Since then, before every competition, I watch my surroundings like a perch so I don’t miss a thing. And strangely enough, a clumsy person was always found. All the girls on our team know that I hold on to shards. And because I was winning, they fell into the same passion as me. How many times did they want to deliberately make some shards before the competition? Dáda Sedláčková was always the most proactive in organizing the shards. Where she went, there were also shards. Whether it was on purpose, I still haven’t found out. However, the prepared shards do not count anyway.

At the Olympics in Tokyo, the situation with the fragments was very critical. We were sitting in the dining room, with less than five hours left until the competition, and still not a single shard. It will be a disaster! After all, it is impossible that in such a large dining room, where there is enough glass and china for five elephants, no one could be found who would be able to “make” shards or at least fragments. Without arranging it, we hypnotized anyone who had a glass in their hand. All in vain. Our familiar waiter appeared at the kitchen entrance. He carried a tray full of glasses, and as usual, balanced them with the skill of a variety show artist. “I’m betting on him today!” says Dada confidently. “One day, he must finally drop it.” — “This one? You won’t get that… Just take a look —” I didn’t even finish. The waiter stumbled and the glasses clattered. We all threw ourselves on the ground and each wanted to catch the largest shard. None of the others knew what was actually happening. The competitors soon understood, but not the Japanese waiter. We thanked him profusely, bowing in Japanese, chirping one over the other “domo arigatou, arigatou, domo arigatou gozaimasu” and setting the shard on our palms as if we were thanking him for it. He shrugged uncomprehendingly. It is apparently only a Czech superstition. Until suddenly, as if something occurred to him, he ran off and in no time carried six new glasses on a tray. At any cost, he wanted to force them on us as souvenirs — what are we supposed to do with such fragments? He was not surprised that we did not receive his attention.

So even before the Olympics, there were shards, and there was also luck.

No one would believe that leaving important things to “someone” else or “something” else is beneficial. A person does not feel the responsibility only on his shoulders, and any failure can easily be attributed to the mascot, talismans, and even shards.

By the way, I haven’t seen even a sliver here in Amsterdam!

…we came to the bars. There, the tallest of us, I think it was the Swede Lundquist, introduced our group to the chief judge, Mrs. Demidenko from the USSR. My biggest rivals, the Soviet Union competitors, took to the balance beam.

During the warm-up, I was upset, and my legs and arms felt like lead. This was partly influenced by the knowledge that I have to defend the victory from the last European Championship in 1965 and that my start at the World Championship in Dortmund last year became a big question mark for me. At the time, many people advised me to take a year off, start working and forget about myself. Even my former coach Vladimír Prorok was of the same opinion: “Believe me, take a moment to relax, those women (by which he meant the judges) already know you too well, they know in advance what kind of performance you will perform — they probably find it too boring when the same woman keeps winning. Who wouldn’t welcome a change? She came: Kuchinskaya. She had the advantage in Dortmund that she was not overly familiar. Her every movement, every element was new for the initiated — she could shine all the more. It is understandable. In a year or two, it will be the same with her as it is with you now. It also makes it ordinary. Now it takes a little more strategy — thinking! You will see that your time will come again.”

Maybe Vladimír Prorok is right after all. He is certainly right. His advice was mostly correct. But retreat and go away without a fight? Run away? Give up? I wouldn’t like that very much, it’s not my style. I should prepare and not give up Amsterdam! Because of the people! Because of those who write me those nice letters and who like me. And that it was a fact, I only realized that after Dortmund, when I was at my worst. I received an awful lot of letters then, even more than after the victory in Tokyo. And then one must value such friendship. I have to do something to deserve it. So that I don’t disappoint.

I will not give up on Amsterdam! And I will not defend myself, I will attack.

*

So I decided three months before the championship. Slávka Matlochová was very happy with my decision at the time. She said she had no doubt that I would return.

We started to train with renewed vigor. We were just inventing new exercises and variations! I would have to practice for at least another ten years to apply them all. We redid the routines in their entirety, I included at least one new element on all the apparatus. We subjected everything to preparation. I felt great, as if I had been changed. I started looking forward to Amsterdam tremendously, and that has not happened to me yet. To give my training a more fun character, Slávka and I wrote its characteristics in rhymes. It was tremendous fun. I always brought my diary to Slávka after the end of the training and she, without thinking and thinking for a long time, always put some rhyme together. Sometimes it’s enough to read the keywords, and I immediately remember the whole training.

“Ach, Bože — nesó hode každý deň!! [Old Czech folk song]” The very next day: “ Čí só hode [Czech folk song]” In the bracket are credited: five optional balance beam routines for 9.7, 9.85, 9.9, 9.9, 9.95, ten compulsory balance beam routines for an average of 9.70 points, three times the entire optional bars routine and ending with 9.65, 9.80, 9.75, five compulsory ones of a fairly decent level, two full floor routines over 9.65, and finally twenty-five vaults. Slávka gave me points for every training set, which had the advantage that I learned to concentrate perfectly at the same time. I never took anything easy in training. On the contrary, I deliberately handicapped myself, raising the bar. Once I came up with an idea. I asked the pianist Ruda Kyznar to run around the balance beam during the optional set, run over it, and make a mess. I wanted to know how much it would bother me. Ruda accepted my wish with enthusiasm and pulled such a prank that I had to stop halfway through. So I laughed. By the second set, I was already able to concentrate so much that it didn’t help Rudo even if he threw paper balls at me, or if he hung onto the rings, swung, and landed directly on the beam. Slávka was in a playful mood at the time, she took a broom from the corner of the gym and started knocking me down with it. It was no use either. So she sat down on a broom, like the witches of the fairytales, and began to circle the beam with a wild scream and leap. We were exhausted from laughter, but I still managed to finish the routine. However, such moments were exceptional in our training.

[Side note: Kyznar was praised for his accompaniment at the 1966 World Championships.]

I also made my training more difficult by sometimes working out on the worst equipment in the gym. I vaulted from a fairly ordinary, hard board. I had to exert much more effort during such a vault than was necessary on a Reuther-type springboard. It only paid off in the competitions. I even practiced with a cast on my leg and tried to practice some uneven bars exercises. Later, I attached a plumb line around my waist and tried to exercise with a five-kilogram load as easily as without it.

[To learn about the different types of boards and their history, head over to this post.]

Over time, a person comes to more and more new forms and methods of improving their performance, submits to them, and thus also becomes a real competitor. A true competitor cannot bear the feeling of any underestimation of his performance. Feelings that he easily and cheaply achieved victory, he considers undignified.

*

Yesterday’s headline from the Dutch newspaper Het Parool appears again in front of my eyes: “VERA CASLAVSKA HEEFT ANGST'” (Věra Čáslavská is afraid!) I realize that I have to shake off the weight, that I have to pick myself up. My turn will come soon and I won’t be strong enough! The Swedish woman with the number eleven has finished her routine and is sadly leaving the bars. She messed up what she could.

Twelve, my number, appeared on the light board. I suddenly feel very suffocated; I cannot catch my breath. The Swedish woman on the bench is sobbing, and I suddenly can’t believe in myself. I walk to my starting point in front of the bars. I adjust the board and check its distance. My hands are sweating. I rub them on my leotard, but it doesn’t do me any good. I can’t jump like that; my hands would slip on the first spin! I return to the competition bench, to the box of white powder. Again and again, I thoroughly rub the magnesium into my palms.

The hall fell silent; I feel everyone’s eyes fixed on the bars. Spectators, competitors, judges. I feel that I am being looked at and judged. I don’t like this oppressive feeling. A greater or lesser number of people look at me all the time, but now it seems to me that the title of European champion is hanging in the balance and that everyone is counting on it. I stand again in my starting position in front of the bars and feel that my fingertips are getting wet again. I mustn’t let it depress me -— I must jump now! Going back a second time would be a shame.

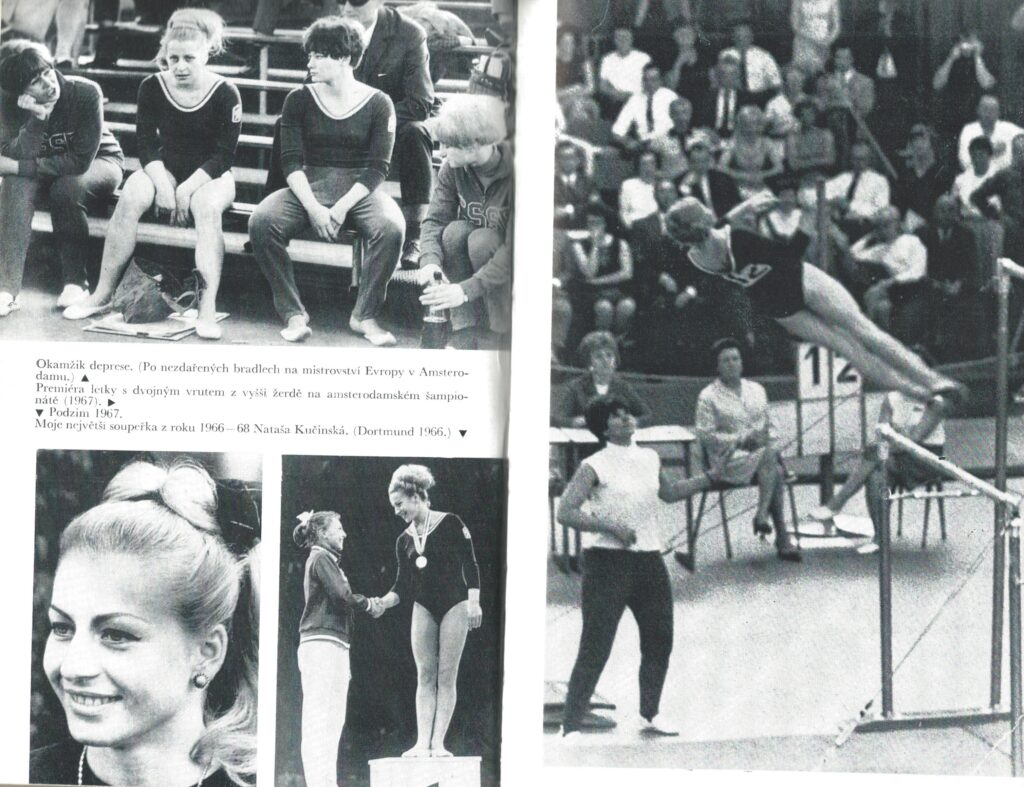

I stepped forward, holding on to the reins, slowly starting to play with them, conquering them, and they obey me. Dear bars — I think, but I shouldn’t have said it. I overturn the turn. The hall howled. I already know that sound from Tokyo. A chill ran down my spine. Well then! I say this to myself and suddenly all the nervousness, fear, and anxiety left me. I’m still trying to save what I can, catch the rhythm again, and mask the break in the spin. Managed. Before the finale, during the final hecht with a full turn, I didn’t even hesitate, as is my habit. When I have already messed up the routine, let me at least make an impression — and I strongly bounce with my abdominal muscles from the higher bar into the dismount. I leave the bar, fly over both bars… I closed my eyes, rotated my hands, and said to myself: “May the Lord’s will be done!” God must have felt sorry for me, so he helped me in the end. I landed well, but it was of no use to me. Gloomily, I went to the corner, I didn’t cry — I just stared blankly in front of me and tried to avoid Mrs. Matlochová’s gaze.

The judges got together and began to discuss my performance. I suddenly didn’t care if they gave a mild or a radical sentence, it didn’t matter to me anymore. If I didn’t perform a masterful composition, give me a zero — just let me go home! Home and away from here — Prorok was right. I shouldn’t have come here. Such a disappointment! All is lost! Finally! Even if I outdo myself in other disciplines, it is not humanly possible to make up for a half-point loss in this competition.

I looked sideways at Slávka. It wasn’t hard to guess what she was thinking.

Photo on the right: “The premiere of the hecht with a full twist from the upper bar at the Amsterdam championship (1967) / “Premiéra letky s dvojitým vrutem z vyšší žerdě na amsterdamském šampionátě.”

*

…In Sofia, right now exactly two years to the day, I won the all-around title at the European Championships for the first time. I also started on bars, but that was a completely different exercise. It was also then that the bag of pre-competition predictions was torn open. It was 1965, a year after the Tokyo Olympics, and the Soviet Union had a new gymnastics champion, Larisa Petrik. I would not like to hurt anyone, but I think that Larisa Latynina became a victim of her home gymnastics experts then. The Soviet Union’s long-standing gymnastics rule had become a matter of course for everyone, and therefore many Soviet officials did not want to allow change. They foresaw that, if they themselves wrote off the overly familiar personality themselves, they would avoid the international panel of judges. A month after Tokyo, Larisa Latynina was defeated again, by a new, completely unknown gymnast, whose performance was unknown to anyone in the world. Larisa Petrik had a journey to Sofia lined with roses and praise. I felt sorry for Latynina then. Larisa Latynina was truly a great figure in world gymnastics, her versatility, gymnastic maturity, and competition experience deservedly brought her to the gymnastics Olympus, and for a long time, there was no gymnast who had a chance to threaten her.

[Reminder: Čáslavská defeated Latynina in the all-around in 1964, and then, Latynina came home and was defeated by Petrik. You can read Latynina’s reaction here.]

I will never forget the scene from Sofia. There was a small press conference in the reception of our hotel. Three of us were invited there — Larisa Petrik, Larisa Latynina, and me. Latynina sat in seclusion the entire time, overlooked by everyone, not promoted by anyone. Just written off in advance. No one took her into account, everything literally revolved around an unknown girl who had not yet achieved anything and who was crowned with glory even before the competition. That’s when I told myself that I mustn’t give in, that I mustn’t let myself be provoked into some kind of rudeness. I promised myself that I would also perform a little for Latynina. I performed well during the competition, I went into it calmly and with perspective, I was determined enough. At the moment, when I was performing my beam routine, Larisa Petrik entered the hall. The spectators were literally ecstatic with her presence, perhaps it didn’t even occur to them that they could disturb the other contestants with their noise. But it didn’t bother me too much at the time, or rather, I was prepared for this eventuality as well. After all, at home Ruda and Slávka secretly trained “strong nerves.” Then, during my beam routine, the situation developed in a very strange way further; some of the audience realized their tactlessness and started shouting at others. The hall seemed to turn into a pit of snakes — hissing and hissing… First the right tribune, then the left. When I finished the exercise, I was glad that I didn’t fall. Even the audience somehow realized it and applauded me from the bottom of their heart.

The next day was the final: our great fan and supporter, football [i.e. soccer] coach Rudolf Vytlaćil, who worked in Bulgaria as a coach of the Levski Sofia club, was also sitting in the audience. The footballers said about him that he has a rare gift, he can get the players so excited for the game before the game that they go crazy in the good sense of the word. They are able to release their souls on the field. When we got to the first apparatus, which was vault, Vytzel was sitting right next to the horse and waving at me eagerly. I didn’t know what that meant and ran to him. His face radiated such mesmerizing optimism and enthusiasm that I was afraid he might make me crazy too.

What did he want? He wanted me to take first place.

I managed to win a gold medal on vault. We marched to the bars. During the introduction, I just involuntarily looked into the audience, and who is sitting right by the bars? Mr. Vytlačil. I started to enjoy the game very much… I wanted to make him angry by not looking at him at all. I stared ahead with a stony expression, but to the right of the bars, I again felt a vehemently waving hand with a closed fist and thumb sticking out. He’s a hydra! Perhaps he wouldn’t want me to win everything here! And indeed: the gold medal did not escape me again. When I then went to the balance beam and floor, Rudolf Vytlačil was sitting there as well. I deliberately buried my head between my shoulders, I didn’t even move, I didn’t look anywhere. Anyway, the hall turned into three thousand five hundred Vytlačils and I began to worry that I would have to leave not only my soul, but also my leotard there. I won two more golds, and it was over. The Czechoslovak national anthem was played five times that day. Both the musicians and the audience had a blast — they certainly learned the anthem by heart.

After the competitions, a Bulgarian lady came to me and asked me to give her sick son cheese in Prague, which he loves more than anything else. What choice did I have? Of course, I didn’t refuse and told the lady to bring the cheese. She pulled the package. I was unhappy; everywhere I went there was a lot of cheesy smell! I was embarrassed. The cheeses could not be shoved either in the trunk or in the bag, simply nowhere. At the airport, when the Bulgarian officials and journalists were saying goodbye to me, the cheese invasion reached its peak. As a newly crowned queen, I wanted to look a little noble, so I always forgot the cheese somewhere, I pretended it didn’t belong to me. Sometimes, however, a good guy was found and brought the package to me with an appreciative smile and did not forget to add that he had seen me on TV yesterday. People walked around plugging their noses and some ladies dipped their noble noses in cologne and Rosa perfume. I remembered the tale of the ferryman who had to ferry for eternity until he found a victim and forced the oar into her hand, and I thought I’d give it a try. It was my last chance. Ruda Kyznar soon became the victim, and strangely enough, he was a gentleman… He patiently walked back and forth with the package, red up to his ears, and I just waited for him to snap and throw the package at my feet. He endured it all the way from Sofia to Prague; passengers one by one left the places near him and changed seats. I sat next to him, but I shouldn’t have. I let the cat out of the bag! Ruda thought he was sacrificing himself for me, but when he realized that it was for some hungry guy, it was over. In the lobby of the Prague airport building, he placed the cheese at my feet without saying a word and left. I was left standing quite alone in the deserted hall; the queen with a golden cup and a parcel of cheese. I almost forgot about Larisa Latynina because of the cheese. In Sofia, she again proved her gymnastic qualities and took second place, while Radochla and Petrik were third [and fourth, respectively]. I think that was Larisa’s last good competition. A year later, in 1966 in Dortmund, she was no longer enough for the young Soviet girls. Today, here in Amsterdam, she is a coach and I think she is happy.

*

It will be an eternity for me until this cruel Amsterdam is over. I looked at the beam. Zinaida Voronina-Druzhinina just finished her training, and her 9.80 speaks for itself.

Natasha Kuchinskaya enters. She performs calmly, confidently. Why not! After all, she’s already half-won! A score almost on the border of ten!

[Note: Kuchinskaya scored a 9.766 on beam.]

A feeling of indifference almost came over me. I suddenly don’t care how the competition turns out, I don’t care that I was once an Olympic champion and a world champion. One thing is that I won all five gold medals at the last European Championship and that it would be appropriate to defend them. I don’t care about everything now and I don’t even care. And that is the worst thing that could happen to me here in Amsterdam.

I remembered the bold letters again: VERA CASLAVSKA HEEFT ANGST! Where did Mr. Kob van Dijk get that I’m scared? After all, I was perfectly prepared! During my training sessions in Amsterdam, the doors were open in the gym, the interest was unprecedented. The gym was always full of spies, but my friends also came to see my new sets and original elements. Many gymnastics experts — mostly coaches — assured me of victory. After my training, the chief judge Mrs. Herpich from Hungary also came to see Slávka Matlochová. She did not hide her amazement at how much progress I had made since Dortmund: “After all, it’s a completely new Čáslavská!”

The buzzer gave the instruction to change apparatus, we marched to the balance beam, and the balance beamers led by Kuchinskaya went to floor exercises. Actually, I didn’t really notice it all, I just let myself be guided automatically. There were also a number of Czechoslovak tourists sitting in the audience, and they all, as if they had agreed, crowded around one after the other and came to comfort me.

Slávka came, took me aside, and tried to convince me that I had to pick myself up, that I mustn’t give in, and also that all is not lost yet. I know very well that this time she didn’t believe her words too much herself, but she still led her way. That really bothered me. “Please leave me alone. You yourself know best that it is all pointless. There is no help here!” — and I made it clear that no one could do anything with me. I surrounded myself with an inaccessible wall — I became horribly allergic to encouragement. “Věrka, if you had at least given me a hand, you would have seen that we would somehow manage it all,” she almost begged. But somehow, all in vain. I was like a stone. “Verka, then at least the little finger would be enough for me. Just wanting a little more.”

I felt sorry for Slávka… In the end, she was so hard on me that she didn’t even leave the gym recently. Because of me, she didn’t even get to go to the cinema, for a walk, anywhere. She did everything just to keep me in good shape. “So what do I do?” I asked resignedly. “Stretch your body a little, jump on the beam, it’s your turn, and then warm up in the next hall — there’s a low beam. Those comforting dirges won’t help you at all right now. I’ll come and get you when the number 11 is performing.”

I obediently obeyed. There was not even a foot in the next hall, there was an almost sacred silence, no screams, no sighs, no people. Slávka hit the nail right on the head. The calmness is a real balm for my nerves. I did a few flips, a pirouette, a forward handspring to the end… “Verus, come on,” she appeared between the doors and smiled angrily. She was very tight; I recognized it in her — her voice was almost stuttering. She had it far worse than me now. I wanted to tell her that I’ve found myself again, that I’m going to step into it now, but I didn’t find the courage. I followed her in silence.

Just as I entered the hall, Kuchinskaya had finished her floor exercise. The hall roared with enthusiasm. Natasha turned in all directions and thanked the crowd. At one point our eyes met. I didn’t cringe this time. I suddenly became angry, I was angry with myself, with my earlier helplessness. But this anger was like a spark. Indifference fell from me and I saw only a beam in front of me.

Twelve lit up. I step in front of the beam for a while, thinking about what to do in order to jump well, I realize where I have to be especially attentive and alert… Suddenly — snap! Shards! Someone dropped a glass in the auditorium. Slávka and I looked at each other. The tension eased.

When I was on the balance beam, I realized that I had completely forgotten about the competition. Nothing weighed me down, nothing could upset me. I was calm as never before. I’m like a breeze. All fears disappeared and I could only drift with movement. I felt good, I wanted to give people beauty. I just wished for that.

I finished the exercise, people stood up, and applauded for a very long time. I had to go and bow again and again. Slávka Matlochová was smiling and her tears were flowing. She was happy. A score of 9.95 points. Ruda Kyznar also came running, stomping his feet three times (he does this when he wants to say something important): “Vero, about halfway through your set I found myself singing along to it, and quite loudly. People started turning around and probably thought that I had skipped a beat.”

[Note: Čáslavská scored a 9.833 on beam.]

After balance beam, I was convinced that I would win. It’s bold, but I was more than sure of it. Until now, I have never dared to prophesy, even in the smallest competitions. I started calculating and planning. Kuchinskaya now has 0.35 more.* I have to gain an extra tenth on the floor exercise, and the vault has to be two-and-a-half to three-tenths better. Now I’m at an advantage! I will always go after Kuchinskaya. For me, it’s a perfect position, I can direct my performance. The high level of my opponents can provoke me to perform, which I would not be able to do under normal circumstances.

[Note: Kuchinskaya was ahead by 0.333 after two rotations.]

I have floor exercise in front of me, I’m trying a salto with a full twist. I’m doing well. Even the flip to sit-down was exceptionally good. I try more acrobatic lines, jump variations and I feel that people are watching me with interest, that they are starting to cheer me on. That always helps me a lot.

[Note: In the video of Čáslavská’s routine from event finals, she did not perform a full-twisting salto.]

Rudo’s moment will come now. He’s already very uncomfortable, sometimes he struggles and at times I catch him strumming his fingers in the air and stomping like he’s pressing the pedals.

The first notes of Smetana’s Vltava were heard. I stand in the middle of the green carpet, my head bowed. The music begins to conquer me; the green area reminds me of the velvet meadow from my childhood — all I miss is the cheerful yellow dandelions. The middle part, the cheerful pattern of the little girl, possessed me and filled the entire space of the carpet. In the first row, directly across from me, sat an elderly lady tapping her feet to the beat — her face performing with me. She put a smile on my face and it stayed there until the end of the set. The score of 9.90 was not enough for the audience, they forced a higher one.

[Note: Čáslavská was known to embellish a bit. She scored a 9.866 on floor.]

Natasha Kuchinskaya sensed that there was a turning point in my game. She got nervous. She completed the vault with a score of 9.60 and was preparing for bars. All that awaited me was the vault, my favorite discipline. In the warm-up, I flew with vigor and spark, nailed all the vaults. Even the spectators got excited, watching each of my warm-up vaults with tension and cheering. I was touched emotionally by them.

Kuchinskaya started on uneven bars. Her routine flows as smoothly as a river, it seems she will be well-regarded.

She fell! In a similar element as I did a while ago, but the accident made her more nervous, she couldn’t react so quickly. Her fall made me very sad. I suddenly felt very sorry for Natasha. When a person is in trouble, he reveals his true face and shows what he really is. At that moment, Natasha was at a loss and scared like a child. I forgave her all the pretense so far. And then, I have never enjoyed the benefits of another’s misfortune and wrong. I’ve always wanted to excel in hand-to-hand competition. All things being equal, be better!

Even though I know that the greatest skill of a competitor is to control the nervous system, even though I know that the competition, not the training — is decisive, I still wouldn’t like the knowledge that I won only because Kuchinskaya fell, I will “return” to Natasha her lost point. I don’t need it. In order to win regardless of her fall, I would have to vault a “Yamashita” for 9.85 points.

I vaulted for 9.95 and thus defended my Sofia European title. I was satisfied, another successful competition.

[Note: Again, Čáslavská did not score a 9.95 on vault. Rather, she scored a 9.833.]

*

We live in a cute guesthouse, from the top floor, where we have breakfast; we have a nice view of the city. Our guest house is separated from the canal only by a path and a yellow strip of tulips. Brightly colored boats filled with bananas, apples, oranges, and all sorts of other goodies race along the canal, adding an exotic touch to the spectacle. Everything here in Amsterdam seems like a fairytale to me. We found ourselves among nice, friendly people who make us think at every step and have only one wish — that we are satisfied with them.

Our guest house is run by motherly Mrs. Nora, and every morning she prepares delicious tea with a beautiful aroma. Slávka and I live in a cozy little room, kind of like grandma’s. The left wall of the room is filled with large oak cupboards with hand-carved ornaments, under the small square windows, which are at ground level, a forged chest lies dignified, and to the right of the huge beds, we are warmed by an ancient fireplace, surrounded by statuettes and vases. The armchairs are covered with slightly faded burgundy velvet, and a small round table invites you to various mysterious games. Wooden sticks sometimes click on the windows, and then I quickly run to see who it belongs to. Or so I imagine. Nice game. It’s a strange sight — seeing only people’s feet.

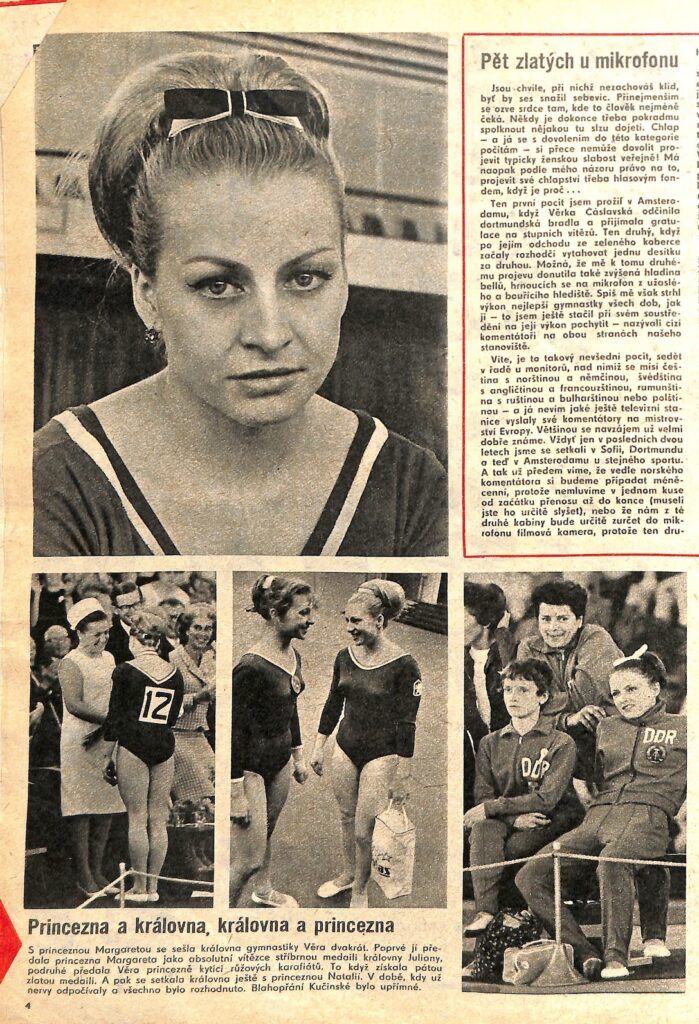

A moment ago, the legs also walked this way —- slender and noble. Didn’t they belong to Princess Margaret? It is said that she sometimes goes out into the streets alone, and her royal parents are worried about her so that she doesn’t get lost. It is said that they send a chamberlain in a black tuxedo to check on her at a suitable distance. I know for sure that the black patent leather shoes were also walking, or rather walking, behind those noble feet. Princess Margaret must have gone this way.

What is life like for such a princess? Probably not very easy. She has to be nice to everyone from morning to night, do everything the royal rules prescribe, and entertain boring suitors who consider it an honor to kiss the hem of her dress. She has a bad time with grooms. There are fewer and fewer princes and choosing from two or three must always be a big risk and boring. It really isn’t much fun being a real princess. I think the gymnastic princess is better off. She, not her parents, can choose a groom that pleases her, a goldsmith or a blacksmith…

Athletics [i.e. track and field] is said to be the queen of sports, and gymnastics, one of the princesses. Emperors, kings, dukes, and all sorts of rulers have always been required to rule justly, wisely, and honorably. Many rulers failed to do so, but the Queen of Athletics did. It is supremely fair to those who serve it. It determines the place on the most sensitive scales of justice.

Athletics does not like boastful words, it requires hard, honest work and eternal dedication. Lazy ones, cheats, and tricksters lose its favor. It richly rewards those who sincerely love her. It is rewarded with a healthy, flexible body, a cheerful mind, friendship with many athletes around the world, and the rare joy of a bloodless fight, when a person wins not only over others, but especially over himself.

This is the confession of the crown prince of the summer of 1964 about his beloved empire, the kingdom of athletics.

And Princess Gymnastics?

…When she was born, it is said that two little judges were standing by her cradle, wondering what to give her as a gift.

The first said: “I give you extraordinary beauty.” But the second added:

“I am giving you judges who will judge your beauty. Disputes will break out between them because of you.”

“You will be able to dance as easily as a butterfly, you will float like a light breeze,” says the first judge again. “You will do everything like a soldier exactly according to the orders of your judges,” the latter cannot be put to shame.

“You will be able to jump and run like a doe…” — “Yes, but your running, your leaps will again be guarded by my judges, and no frolicking will be tolerated.”

“Your agility and flexibility will be the envy of even the court acrobats, you will be the center of admiration of many people” — “You will have to work hard, your hands, even those of a princess, will be covered with bloody calluses.”

[Note: To English speakers, a fairytale seems bizarre, but pohádky (fairytales) are a vibrant genre in Czech culture. To get a sense for the genre, you can watch part of the Proud Princess (Pyšná Princezna, 1952) on YouTube.]

It is said that those judges stood at the cradle of our princess for a long time and attributed many other qualities to her that I don’t even know about. Now she has grown out of baby shoes and is experiencing the most beautiful age. She has already shown a whole range of qualities and is certainly still hiding a number of them. Like the Queen of Athletics, she also lends her golden crown every year. The girl who most matches her ideas will win it.

But the fairytales are over…

Slávka came from the meeting of the technical gymnastics committee and brought the draw for tomorrow’s final competitions.

*

The hall opened her arms wide to me. After yesterday, it became quite familiar to me, and I was very much looking forward to it today.

We marched into the hall. For a few moments, people stand up, and the princess enters the hall. But what is my disappointment — the princess has neither a veil, nor a long dress, nor a crown. She is not the princess from my fairytales at all.

She came accompanied by several venerable gentlemen, and they led her to a small step covered with a plush carpet. The Princess thanked everyone for the welcome and announced in French that the final competitions of the 1967 European Championship had begun.

The competition started, as always in the finals, with vault. It doesn’t mean too much nervous tension for me, I can concentrate and coerce myself quite well. I remember Eva Bosáková, who hated vault to death. It often happened that she ran several times, didn’t find the courage to bounce and fly through the air, and… braked. More than once she got a zero for vault, and that understandably discouraged her. She lost a lot of important competitions because of vault. Maybe I wouldn’t even understand similar conditions if it weren’t for my injured elbow and a longer break from vaulting. That was the first time I knew what it was to be afraid to vault.

Vaulting requires ferocity, strength, speed — but above all, determination. Those who are afraid, hesitate, usually don’t vault. Because I knew Eva Bosáková’s bad mental states and experienced them myself, I never allowed myself to admit fear. I then fixed this principle so much that I could vault even in the dark. Now I’ve gone a bit overboard again. I’m afraid of the dark. And I wouldn’t have to worry about it either.

I didn’t have much of a chance on bars. The qualifying score from the first day was modest. And perhaps precisely because I didn’t care about anything, I performed safely and cleanly. Druzhinina [i.e. Voronina], who had the opportunity to win a medal, couldn’t stand her nerves. She screwed up.

So I repeated the journey to the first step again and began to realize that it wouldn’t be bad to try a Sofia repeat. It was a bold idea, so I kept it to myself.

The balance beam was one of the best exercises I’ve ever done in my life. I was very happy with it. I was very surprised by the chief judge, Mrs. Herpich from Hungary, who then created an interesting scene. When I finished the exercise and dozens appeared at the judges, she waved a red flag and called me to her. Why? After all, everything corresponds to the rules! The judges have agreed, and there is, therefore, no reason to discuss the performance again. We didn’t know what actually happened for a long time, I even started to think that the length of the routine was not according to the rules.

Nothing like that. Ms. Herpich only briefly announced to the judges: “It’s not usual, but I wanted to thank you. The routine of Čáslavská was absolutely perfect!”

But then again, I was thinking about floor exercise. I quickly opened my eyes and rested for a short time to gain enough strength. I took two sugar cubes out of my bag and bit into a lemon… An editor from Prague was just passing by me. He said he would be very happy if I wasn’t so brooding and cold on the podium. “That needs a little more cheering, frolicking, and waving!” — “I guess you don’t know me very well” I defended myself. “I don’t like such jumping at all, it seems undignified. You may not believe me, but sometimes I don’t even have the courage to wave at people! I’m afraid they’ll think I didn’t deserve it and that I want to buy them now!’

I feel the most uncomfortable on the podium, and it is a paradox that I strive for the podium so much. Whenever I stand on the podium for too long, I look for salvation in the other competitors who will also be there, and we share the audience’s attention. I never know what to do with my hands or where to look. That’s why I usually stare at the ground.

Fanfare sounded, and military music prepared for a roaring march. Everything was repeated, the same face in front, the same facial expressions, the same walk, the same hymn. I could not understand why the Dutch were not bored during the fifth Czechoslovak anthem.

Our national anthem played, we were decorated with medals, and we received beautiful flowers. I descended the step and walked across the competition carpet to where Princess Margaret was sitting. I gave her flowers. For me, it was a more sympathetic thank you to the Dutch audience than exaggerated empty gestures from the podium.

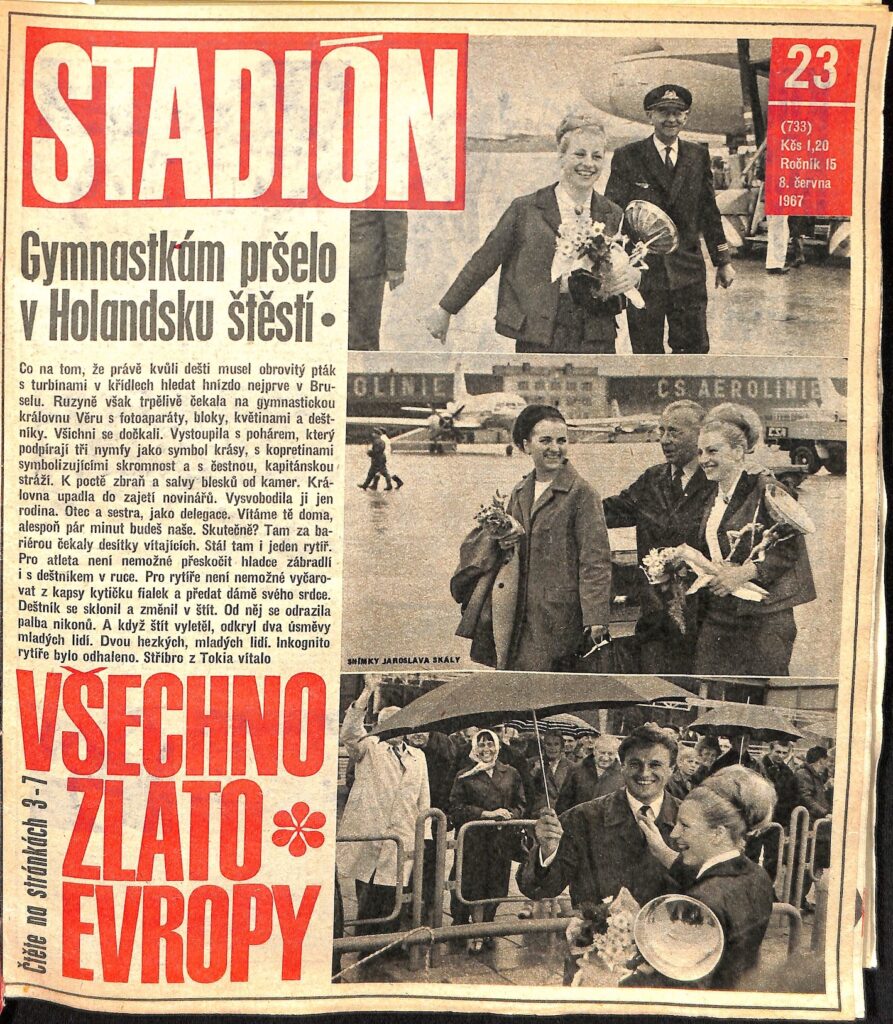

Many friends and acquaintances came to the Ruzynské airport in Prague, my father came with our Eva.

-.. someone I liked also came, and Stadión [a Czechoslovak sports magazine] revealed it:

Stadión, June 8, 1967:

… What about the fact that precisely because of the rain, a giant bird with turbines in its wings had to look for a nest in Brussels first. However, Ruzyně waited patiently for gymnastics queen Věra with cameras, notepads, flowers, and umbrellas. Everyone was waiting. She emerged with a cup supported by three nymphs as a symbol of beauty, with daisies symbolizing modesty, with an honorable captain’s guard. A gun and shots from the cameras as a tribute. The queen was captured by journalists. Only her family freed her. Father and sister, as a delegation. We welcome you home, at least for a few minutes you will be ours. Really? There, dozens of welcomers were waiting behind the barrier. There was also a knight standing there. It is not impossible for an athlete to smoothly jump over the railing even with an umbrella in hand. It is not impossible for a knight to conjure a bouquet of violets from his pocket and give the lady his heart. The umbrella bent down and turned into a shade. Nikon fire bounced off him. And when the shield flew up, it revealed two young people’s smiles. Two beautiful young people. The incognito knight has been revealed. The silver of Tokyo welcomed all the gold of Europe.

[Note: This paragraph was on the cover of the magazine issue, which you can see below. The man in question was Josef Odložil, whom she married after the Mexico City Olympics. The couple divorced in 1987, and in 1993, Odložil died after a fight with their son.]

… so my fairy-tale narration, without my doing it myself this time, lasted all the way to Prague.