Čáslavská’s beam routine during the optionals portion of the (1B) competition caused quite the stir.

Here are the basics:

- Čáslavská received a 9.65 for her beam routine.

- The crowd protested for over 10 minutes.

- Her beam score was raised to a 9.80 after Berthe Villancher, the president of the Women’s Technical Committee, interceded.

There was a lot on the line. These scores counted towards:

- The team standings

- The all-around standings, which was the sum of a gymnast’s compulsory and optionals scores

- Qualifying for event finals

- A gymnast’s event finals score, which was the average of her compulsory and optionals scores + her event finals score

Let’s get into the nitty-gritty and discuss how this one routine illustrated so much of the judging dysfunction that existed in the 1960s.

Setting the Stage

Here’s an account from the Dutch newspaper Het Vrije Volk:

The shrill protest lasted more than ten minutes as the judges rated Věra’s blazing exercise on the balance beam with just a 9.65.

[…]

Věra Čáslavská delivered a magnificent performance on the balance beam. She only had a slight hesitation once but bounced on without a single mistake to a somersault that sealed the deal.

The valuation was much too low: 9.65 points. The result was fierce booing, followed by the chanted “Věra, Věra,” from the stands. The public had already chosen their favorite by then.

Meer dan tien minuten duurde het schrille protest toen de jury Vera’s blakende oefening op de evenwichtsbalk met slechts 9.65 punten waardeerde.

[…]

Integendeel, de merendeels oudere dames op de jurystoelen hebben kennelijk het plan met harde hand te regeren. Het gevolg was gisteravond een rel van allure. Vera Caslavska leverde op de evenwichtsbalk een grandioze prestatie. Ze had slechts een maal een lichte weifeling maar veerde verder zonder een enkele fout naar de salto die het slot vormde.

De waardering was veel te laag: 9.65 punt. Het gevolg was een fel fluitconcert, gevolgd door het gescandeerde “Vera, Vera,” van de tribunes. Het publiek had toen al zijn favoriete gekozen.

Het Vrije Volk, Oct. 24, 1968

The Swiss newspaper L’Impartial added an extra detail: the judging panel was “presided over by the Soviet judges.”

Indeed, on the beam, the Czechoslovak Vera Čáslavská presented an impeccable routine, and she was awarded by the jury, presided over by the Soviet judges, a score of 9.65. After being copiously scolded, the jury changed the score and awarded the future Olympic champion a 9.80, which is an exceptional fact in the history of gymnastics.

En effet, à la poutre, la Tchécoslovaque Vera Caslawska a présenté une exhibition impeccable et elle s’est vu attribuer par le jury, présidé par les juges soviétiques la note de 9,65. Après s’être fait copieusement conspuer, le jury a modifié la note et a attribué à la future championne olympique un 9,80, ce qui constitue un fait exceptionnel dans l’histoire de la gymnastique.

L’Impartial, October 25, 1968

Why did the Swiss newspaper make a comment about Soviet judges? Well, let’s take a look at who was assigned to beam.

Problem #1 — Conflicts of Interest

According to the working plan, here were the judges assigned to the balance beam for the optionals competition:

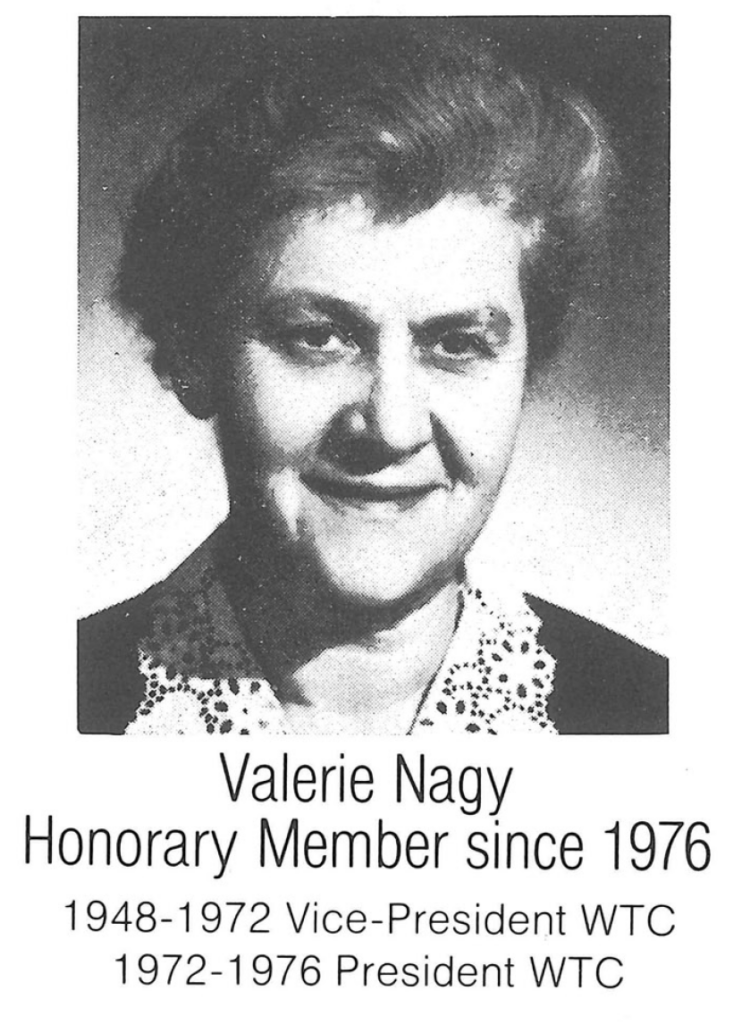

Superior Judge: Valerie Nagy (HUN)

Larisa Latynina (URS)

Jackie Uphues (USA)

Janina Skirlinska (POL)

Ingeborg Hermann (GDR)

The working plan can change on site at the Olympics.

That said, Jackie Fie (Uphues at the time) confirmed that she and Latynina were judges for this beam routine. She also confirmed that Nagy was the superior judge.

Larisa Latynina’s presence on the judging panel should have raised the eyebrows of reporters.

- Not only did Latynina lose to Čáslavská at the 1964 Olympics…

- And not only was she judging her former Soviet teammates from the 1966 World Championships…

- But she was also the head coach of the Soviet team at the time.

Not to mention, how many years of judging experience did Latynina have at this point? (More here.)

To be clear, we don’t know how Latynina judged this routine. But it’s still safe to say that, even before Čáslavská mounted the beam, there was a problem with the composition of the judging panel.

Having Latynina on the judging panel was undoubtedly a conflict of interest. Granted, it was one that the FIG allowed, but it was a conflict nonetheless.

Problem #2 — Made-up Deductions

To gain a more complete picture of what happened, we have to turn to Jackie Fie’s recounting of this beam routine.

A Judge’s Perspective

In 1998, Věra Čáslavská was inducted into the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame, and Jackie Fie (Uphues in 1968) wrote a speech, in which she recalled this moment from the 1968 Olympics:

On Balance Beam, Vera performed a sequence of: walkover forward to a needle scale, finishing with one hand under the beam on one side of the Balance Beam. She faltered slightly. Was it a balance correction (only -0.10) or a grab under the beam to maintain balance (-0.30)? Former Women’s Technical Committee President Valerie Nagy, of Hungary, was trembling in the center of this controversy and judging “rhubarb.” Judges on both sides of the beam (2 + 2) stood firm with their scores. The marks were 9.5 to 9.8 with an average of 9.65, with the judges on one side taking -0.30 and the other side no more than -0.10. The scores from Competition-Ia and Competition-Ib (also the All-Around) carried to the Individual Event Finals. Natalia Kutchinskaya, her rival, ultimately went on in the Finals to become the gold medalist and Olympic champion on Balance Beam.

In other words, the judges were debating if Čáslavská had a small balance check (0.1 deduction) or if she grabbed underneath the beam to maintain her balance during her needle scale (0.3 deduction).

In the judges’ minds, it made a difference where she placed her hands. If she grabbed underneath the beam, it was a clear attempt to maintain her balance.

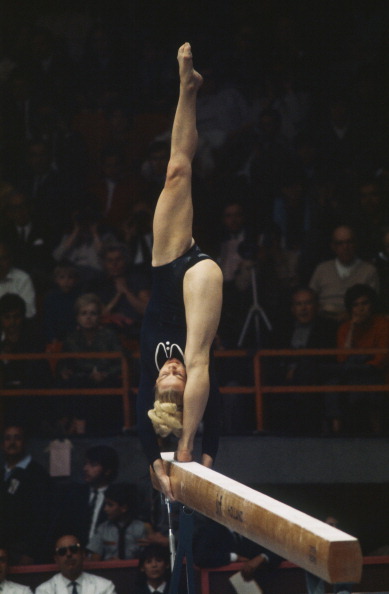

As you can see in the photo below, Čáslavská tended to grab below the beam on her needle scale. (I apologize for the angle; it was the only licensable photo of her needle scale that I could find.)

She also grabbed under the beam at the 1967 European Championships, where she received a 10.0 for her beam routine.

Not Following the Code’s Deductions

When you read Fie’s recollection, a big question arises: Why did two judges take only 0.3 when the deduction should have been 1.0 for grabbing the beam to maintain balance?

According to the Code of Points, here were the balance deductions for touching the beam in 1968:

- Touching the beam to maintain balance was 0.5

- Support of hands on the beam to maintain balance was 1.0

Maybe they didn’t take the full deduction because of Čáslavská’s name and reputation.

Maybe the judges were being lenient because the needle scale came after a harder skill. (On the men’s side, the Code allowed judges to be more lenient with more difficult routines, but that wasn’t the case on the women’s side.)

Maybe they simply weren’t familiar enough with the Code of Points.

Maybe they used the Code of Points as a set of general guidelines.

Regardless, by taking a 0.3 deduction, the judges weren’t following the Code and assigning values to deductions as they saw fit.

That’s a problem.

Made-up Rules

Another important point: The 1968 Code of Points doesn’t make a distinction between touching the side of the beam on a needle scale and touching underneath the beam on a needle scale.

So, if the judges were taking a 0.3 deduction for touching under the beam, they were making up their own unwritten rules.

Problem #3 — Superior Judge: Who does what to whom?

Nagy was the superior/head judge, and it sounds like she wasn’t very helpful since she was judging rhubarb rather than Čáslavská. According to Fie:

Valerie Nagy, of Hungary, was trembling in the center of this controversy and judging “rhubarb.”

Normally, if the judges’ scores ranged from 9.5 to 9.8, Nagy’s intervention should not have been needed. The point spread between the judges was 0.3, which was permissible in 1968.

But since there was a conference when the crowd protested, Nagy needed to intervene.

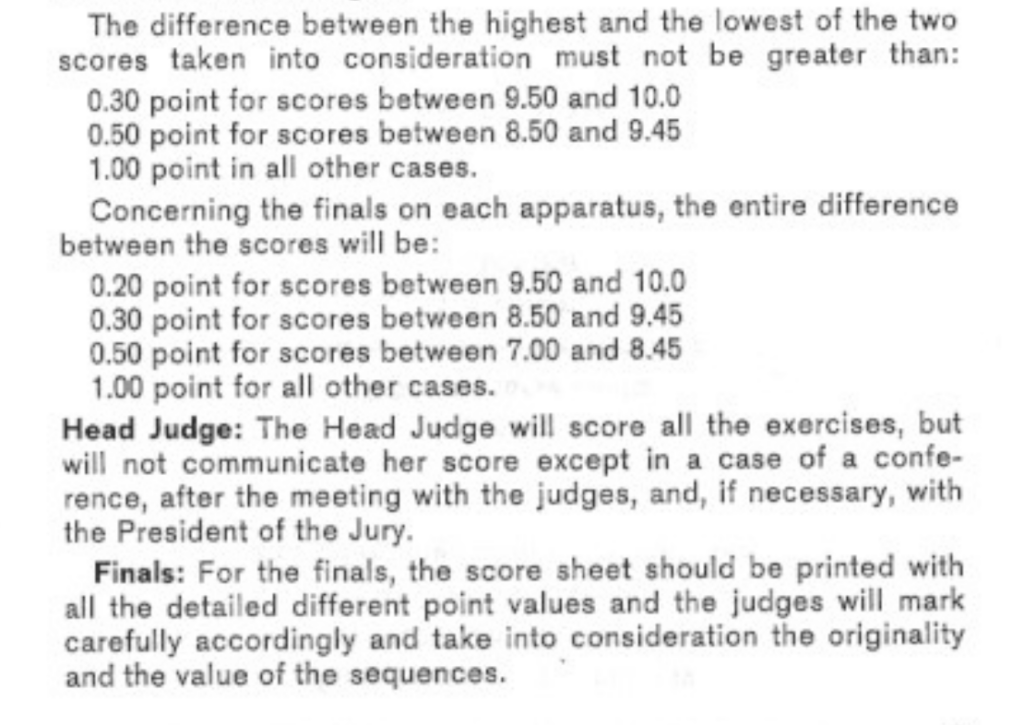

Now, look at what the Code of Points says about judges’ conferences:

Head Judge: The Head Judge will score all the exercises, but will not communicate her score except in the case of a conference, after the meeting with the judges, and, if necessary, with the President of the Jury [of Appeal].

It isn’t clear how judges’ conferences were supposed to be resolved on the women’s side.

What was the protocol for the initial meeting among the judges and the superior judge?

Did, say, the superior judge overrule the rest of the judges?

It’s unclear.

Note: The men’s Code of Points had clear instructions for using the superior judge’s score in 1968. “His mark added to the average of the two middle marks of the four judges, divided by two is the valid basic score. It is used for possible intervention in consultations when needed.” The women did not.

Note #2: After the 1968 Olympics, Nagy wrote an article for Olympische Turnkunst about the competition in Mexico City. You can read it here.

Problem #4 — President of the Jury of Appeal: Who does what to whom?

Nagy wasn’t able to resolve things on her own. Berthe Villancher, the president of the Women’s Technical Committee and the president of the Jury of Appeal, had to intercede:

Amid angry protests from the crowd, Berthe Villancher, president of the women’s technical committee, twice hurried across to the judge-referee in charge of individual apparatus. Once her intercession led to a change in the points awarded (“A marked sign of weakness by the technical committee,” said Nick Stuart, manager-coach of the British men’s team.)

This occurred when Miss Caslavska was given [9.65] points for her work on the beam. There was a sustained, swelling bedlam of shouts, boos, whistles, and hisses, with the noise angrily increasing in volume until the mark was changed to 9.8.

The Times, Oct. 25, 1968

After Villancher interceded, the score was raised to a 9.80, matching the highest-scoring judges on the panel.

While Nick Stuart thought that Villancher’s involvement was “a marked sign of weakness,” it was permissible. Villancher, as the president of the Jury of Appeal, could be involved according to the Code:

Head Judge: The Head Judge will score all the exercises, but will not communicate her score except in the case of a conference, after the meeting with the judges, and, if necessary, with the President of the Jury [of Appeal].

But it wasn’t clear when she should get involved (“if necessary”), nor was it clear how she should be involved. As the President of the Jury, did Villancher overrule everyone else?

There wasn’t an explicit protocol for moments like these.

Problem? Letting the Audience Guide Scoring

The crowd’s shrill protest undoubtedly influenced Čáslavská’s beam score, and I am of two minds on the audience’s influence over the judges.

On the one hand, the judges shouldn’t kowtow to the spectators, whose understanding of the sport should pale in comparison to that of the judges. According to the foreword of the 1968 Code of Points:

By virtue of her particular proficiency and professional value, each judge must be able to appraise and deeply feel (know) the exercise that is presented before her.

Her work is complicated and full of responsibility as she has only a few moments to judge a piece of work that has been meticulously prepared for several months by the gymnasts and their instructors.

The conscientious and impartial jury does not allow itself to be influenced by scenic effects without real value. It (the jury) is capable to observe and understand in its entirety the difficulty and value of a movement, the construction of the exercises, and its harmony with the music.

Women’s Code of Points, 1968

In other words, the judges should be the experts and shouldn’t be influenced by “scenic effects.”

On the other hand, could spectators’ boos and hisses be a way of stopping cheating and score fixing?

Again, we don’t know if there was cheating in this instance, so the spirit of my question is more general. Could spectators’ boos and hisses — generally speaking — be a way of stopping cheating and score fixing?

In Any Case…

It’s amazing how this one routine can highlight so many of the flaws with judging in the 1960s:

- Clear conflicts of interest on the judging panel

- Deductions not being followed

- Judges inventing their own rules

- Ill-defined roles and protocols for the Head Judge and the President of the Jury of Appeal

In my next post, we’ll take a look at what happened during the rest of the optionals competition.

Notes

Note #1: In the end, Čáslavská won the all-around by 1.40 points over Voronina, so the score change didn’t matter.

Note #2: This isn’t the first time a score was changed at an FIG-sanctioned meet. At the 1962 World Championships, Miroslav Cerar’s parallel bars score was changed, making him the gold medalist. His routine made gym nerds question whether the FIG should abandon the 10.0 system.

Note #3: Nagy, the Rhubarb Judge, would go on to become the president of the Women’s Technical Committee in 1972.

Note #4: Some newspaper accounts say that the original score was a 9.60 rather than a 9.65. However, the majority say 9.65, and that’s also what Jackie Fie recalled.

Note #5: I am not blaming Latynina in this article. If the FIG allowed a national team head coach to be a judge, that’s an FIG problem — not a Latynina problem.

Note #6: The problems with judging one’s own gymnasts have been well known for decades. During the Fête Féderale Française de Gymnastique (French Federal Festival of Gymnastics) in 1889, one of the criteria for judges was this:

Art. 1. — Cannot take part in any competition:

[…]

The members of the jury (the latter must in no case direct or lead a Society).

Art. 1er. — Ne pourront prendre part aux différents concours:

[…]

Les membres du jury (ces derniers ne devront en aucun cas diriger ou conduire une Société).

La Gymnastique et Le Moniteur officiel de la gymnastique, du tir et de l’escrime, Nov. 4, 1888

Societies were essentially local gymnastics teams

Fast forward many decades. The FIG was aware of the problems with bias in judging, and on the men’s side, they were trying to determine how. to address the problem.

In 1968, on the men’s side, judges from a country could not judge an apparatus final if a gymnast from his country was competing on that apparatus. For example, a Japanese judge could not judge the pommel horse final if there was a Japanese gymnast from the pommel horse final.

Note #7: This post, though rooted in documents from the time, is my personal analysis. I haven’t found a 1968 article that dove into the problems of the women’s Code of Points. That said, the newspaper accounts and Fie’s recounting suggest that something was off about this beam routine — and it wasn’t just Čáslavská’s connection between her handspring and her needle scale.

More on 1968

2 replies on “1968: Věra Čáslavská’s Beam Score and the Problems with Judging”

Great article!

Thanks for your comprehensive telling of this historic event!

Great article as usual, for you Tim, who´s the greatest: Latynina, Vera, Olga, Nadia, Daniela, Bogi, Khorkina, o Simone?