At the Olympic Games prior to 1928, the men competed in track and field events, rope climbing, or even an obstacle course (1920).

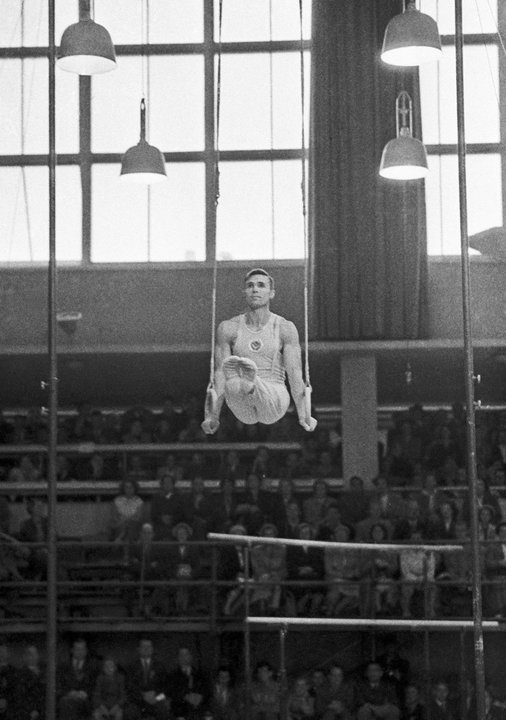

The Amsterdam Olympics marked a turning point in men’s gymnastics. For the first time, the athletes competed only on gymnastics apparatus at the Olympic Games. No rope climb. No sprints. No high jump. Just apparatus gymnastics.

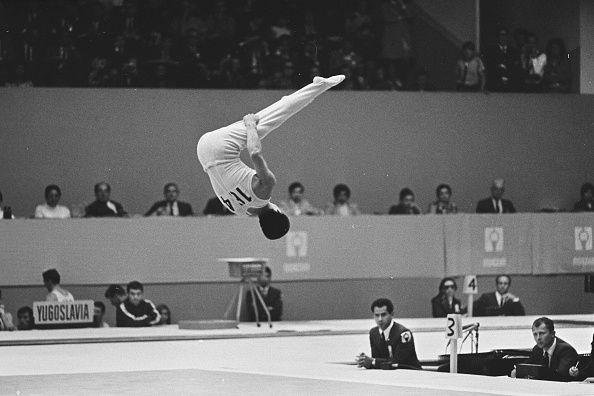

However, the Olympic program still hadn’t taken its modern form. In 1928, male gymnasts didn’t perform individual floor routines. They did, however, perform on the floor as an ensemble, and, as we’ll discuss in the next post, the Yugoslav team had a remarkable ensemble routine.