History is a matter of perspective, and, by extension, so are gymnastics results. As we’ll see, the women’s event finals were highly contested at the 1968 Olympic Games.

Let’s take a look at what happened…

Competition Footage | Results and Commentary | The Price of Protest

Competition Footage

A Few Comments

Skleničková (TCH): Women’s artistic gymnasts were trying to figure out how to dismount the bars with saltos. For example, Skleničková tried to do a cast front tuck. Video below:

Note: Though she didn’t make event finals, Joyce Tanac (USA) competed her Tanac salto or spank back dismount at the 1968 Olympics. (The dismount has had many names over the years.) You can see her dismount in this film from 1969:

Zuchold on UB: She did her Zuchold transition to the low bar.

Her dislocate on the high bar was also extremely popular.

Zuchold on BB: While Zuchold was known for her vaulting, she also helped push balance beam in new directions. She performed a double turn when few gymnasts took that kind of risk.

She also competed a front handspring stepout to barani dismount.

Čáslavská on BB: Even at the end of her career, Čáslavská was upgrading. Her back full dismount off beam was one of the first. (Minot Simons II in Women’s Gymnastics: A History says that Tourischeva also competed the dismount in Mexico City.)

Kuchinskaya on FX: Coming into the final, Kuchinskaya was in first. I love the little details in her routine. For example, her aerial walkover before her second pass wasn’t just an aerial walkover. It was an aerial walkover swing through to a lunge.

Speaking of her second pass… In 1966, Kuchinskaya’s first pass was a back full, and her second pass was the layout 1/2 to a walkout. In 1968, she changed the order, opting to perform the back full as her second pass.

Petrik on FX: After the 1968 Soviet Nationals, Petrik mentioned her inability to hold back, giving each performance her all. You can see it in this performance.

I love her powerful, dramatic opening, leaping down the side of the floor. And I love how that contrasts with the simple (yet captivating) hand choreography in the middle of the floor after her first pass.

Čáslavská on FX: Čáslavská sparkled when she did this routine to “Jarabe tapatío” and “Allá en el rancho grande.” Her back full on floor was new in 1968, and it was perhaps the cleanest, highest full in the finals.

But the real charm of this floor routine was Čáslavská’s ability to draw the crowd in and play with them. Prime example: Fifty seconds into the video below, she, in theatrical terms, breaks the fourth wall and interacts with her audience by throwing them smiles. (“Throwing smiles” is the term she used in Věra 68.)

You can really hear how much the crowd loved her at the very end of the routine.

Judging Assignments

Vault and Uneven Bars

Judge-Referee:

Andreina Gotta (ITA)

Käthe Wiesenberger (AUT)

Carin Delden (SWE)

Larissa Latynina (URS)

Hana Vláčilová (TCH)

Beam and Floor Exercise

Judge-Referee:

Valérie Nagy-Herpich (HUN)

Taissia Demidenko (URS)

Alena Tintěrová (TCH)

Michéle Thiébault (FRA)

Anna Anikina (URS)

Sylvia Hlavaceck (GDR)

Results and Commentary

Date: Friday, October 25, 1968

Reminder: Only six gymnasts qualified for event finals. Qualification for finals was based on the compulsory *and* optional scores on each event.

A gymnast’s final score was the average of her compulsory and optional scores + the score for her routine during event finals.

COA = Compulsory + Optional Average

Who should have won each event?

In this section, we’ll look at what the newspapers said at the time.

Vault

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.875 | 9.900 | 19.775 |

| 2. Zuchold | GDR | 9.825 | 9.800 | 19.625 |

| 3. Voronina | URS | 9.700 | 9.800 | 19.500 |

| 4. Krajčírová | TCH | 9.725 | 9.750 | 19.475 |

| 5. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.725 | 9.650 | 19.375 |

| 6. Skleničková | TCH | 9.675 | 9.650 | 19.325 |

Vault seems to be the least controversial of the event finals. To date, I haven’t found an article that argues for a different champion. It was generally accepted that Čáslavská was the best vaulter.

Reminder: Čáslavská was the reigning Olympic champion on vault, and she had won vault at the two previous World Championships (1962, 1966).

Referring to vault, the Mexican newspaper El Informador wrote on October 29, 1968: “Ésta es la especialidad de Vera.” (“This is Věra’s specialty.”)

Here are additional comments on the top vaulters from U.S. judge Dale Flansaas:

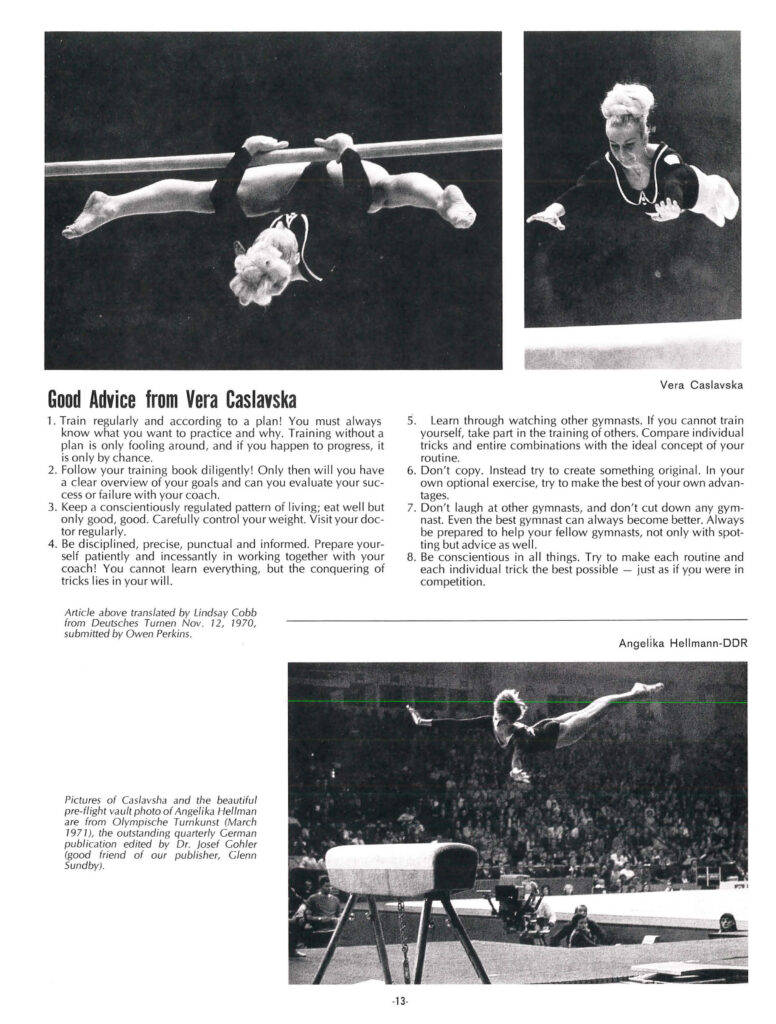

Caslavska hit her normal flighty vault with a perfect landing. Voronina looked like the best Russian vaulter — excellent preflight and afterflight. Her Yamashita was definitely individualized — she thrusted her arms sideward at the height of her preflight before bringing them forward onto the horse. The E. German team also proved to be strong vaulters placing Zuchold and Janz in the finals. Zuchold has low preflight on a Yamashita, but tremendous afterflight.

Mademoiselle Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

Note: It’s not clear if Flansaas was writing about the finals or simply talking about the gymnasts’ vaults in general.

Uneven Bars

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.750 | 9.900 | 19.650 |

| 2. Janz | GDR | 9.650 | 9.850 | 19.500 |

| 3. Voronina | URS | 9.625 | 9.800 | 19.425 |

| 4. Řimnáčová | TCH | 9.650 | 9.700 | 19.350 |

| 5. Zuchold | GDR | 9.525 | 9.800 | 19.325 |

| 6. Skleničková | TCH | 9.550 | 8.650 | 18.200 |

Who should have won?

The East German media intimated that Janz’s routine was as good as — if not better than — Čáslavská’s.

She competed fourth — clean, with strong nerves, and without the slightest trace of a wrong movement. The spectators raved with enthusiasm and did not understand why the Czechoslovak Čáslavská had scored five-hundredths of a point better. Were name and “appearance” particularly honored here? But Karin’s score was enough for the silver medal.

Ihre Übung turnte sie als vierte, sauber, nervenstark und ohne die Spur einer Fehlbewegung. Die Zuschauer tobten vor Begeisterung und wollten nicht verstehen, warum die Tschechoslowakin Caslavska eine um fünf Hundertstel Punkte bessere Note erhalten hatte. Waren hier der Name und der “Auftritt” besonders honoriert worden? Doch Karins Wert reichte dennoch für die Silbermedaille.

Neues Deutschland, October 27, 1968

Balance Beam

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.800 | 9.850 | 19.650 |

| 2. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.725 | 9.850 | 19.575 |

| 3. Petrik | TCH | 9.500 | 9.750 | 19.250 |

| 4. Metheny | USA | 9.575 | 9.650 | 19.225 |

| 4. Janz | GDR | 9.525 | 9.700 | 19.225 |

| 6. Zuchold | GDR | 9.500 | 9.650 | 19.150 |

Who should have won?

It depends on whom you asked.

On the one hand, the Soviet media reported that everyone wanted Kuchinskaya to win gold on beam:

Even on a difficult day for Natalia Kuchinskaya, when a perfectly trained gymnast performed unsuccessfully on the uneven bars, the Mexicans, paying tribute to the skill of the Czechoslovak gymnast Věra Čáslavská, remained loyal in their sympathies to the blue-eyed blonde from snowy Russia, as one of the local sports commentators called Natasha.

So, today we are writing again about N. Kuchinskaya. We are writing because, in Mexico City, we have not met a single person who would not wish her victory in the individual event finals after receiving the bronze medal in the all-around.

Даже в тяжелый для Наи Кучинской день, когда отлично подготовленная гимнастка неудачно выступила на брусьях, мексиканцы, отдавая должное мастерству чехословацкой гимнастки Веры Часовской, остались верны в своих симпатиях голубоглазой блондинке из снежной России, как назвал Наташу один из местных спортивных комментаторов.

Итак, сегодня мы вновь пишем о Н. Кучинской. Пишем потому, что в Мехико мы не встретили ни одного человека, который не желал бы ей победы в Соревнованиях по отдельным видам после бронзовой медали, полученной в многоборье.

Известия, Oct. 27, 1968

On the other hand, there are several newspaper accounts arguing otherwise. Several articles indicated that the crowd was on Čáslavská’s side, which made the beam podium awkward.

The award ceremony for this event was a torment for Natalia Kuchinskaya. When the young Russian girl jumped onto the platform, shrill protests burst forth. And not wrongly. Natalia Kuchinskaya, who showed a wonderful beam exercise with very difficult parts, was valued with 9.85 points, just like Věra Čáslavská. In terms of quality, the exercises of the two gymnasts were not inferior to each other, but Natasha made a small mistake in the beginning, which the jury — especially in this group — should have taken more deductions for. The enthusiastic crowd only calmed down when Čáslavská appeared on the second step. While Natalia Kuchinskaya listened to the Russian national anthem with her face contorted, Vera beamed.

De prijsuitreiking op dit nummer was voor Natalia Koetsjinskaja een kwelling. Toen het jonge Russinnetje op ‘t platform sprong barsten schrille fluitconcert los. En niet ten onrechte. Natalia Koetsjinskaja, die een schitterend balkoefening had laten zien met zeer zware onderdelen, werd evenals Vera Caslavska gewaardeerd met 9.85 punten. In kwaliteit deden de oefeningen van de twee turnsters niets voors elkaar onder maar Natasja maakte in het begin een klein foutje, dat de jury — vooral in dit gezelschap — tot een lager totaal had moeten brengen. Het enthousiaste publiek kwam pas weer tot bedaren toen Caslavska op de tweede trede verscheen. Terwijl Natalia Koetsjinskaja met vertrokken gezicht naar het Russische volkslied luisterde, straalde Vera.

Trouw, Oct. 28, 1969

A similar account of the podium can be found in the Mexican newspaper El Informador:

The public intervened once again in this Olympic contest, yelling “Věra, Věra” and showing their favor for the Czechoslovak gymnast, winner already of three gold medals.

The two Soviet winners in the competition watched the cheers from the crowd with utter impassiveness.

When the results were announced and the audience found out that the Czechoslovak had won the silver medal on beam, there was a real explosion of joy among the spectators.

El público intervino una vez más en esta prueba olímpica demostrando con sus gritos de “Vera, Vera,” el favor en el que tiene a la gimnasta checoslovaca, ganadora ya de tres medallas de oro.

Las dos soviéticas ganadoras en la prueba asistieron con absoluta impasibilidad a las aclamaciones de la multitud.

Cuando resultados fueron dados a conocer y el público se enteró que la checoslovaca había ganado la medalla de plata en la barra de equilibrio, hubo una verdadera explosión de alegría del público.

Informador, October 26, 1968

Tiebreakers to make it into finals

On a separate note, Cathy Rigby’s COA was also 9.500, but since her all-around ranking was lower than Petrik’s and Zuchold’s rankings, she did not compete in the finals.

Linda Metheny remained in 3rd spot and Cathy Rigby tied for 5th with 2 others. So, Linda made finals and Cathy missed out because she tied with 2 and only 6 could be in the finals. Cathy had the lowest all-around of the three.

Mademoiselle Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

Floor Exercise

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1T. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.775 | 9.900 | 19.675 |

| 1T. Petrik | URS | 9.775 | 9.900 | 19.675 |

| 3. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.800 | 9.850 | 19.650 |

| 4. Voronina | URS | 9.700 | 9.850 | 19.550 |

| 5T. Karaseva | URS | 9.575 | 9.750 | 19.325 |

| 5T. Řimnáčová | TCH | 9.575 | 9.750 | 19.325 |

The Myth of Larisa Petrik’s Scores

For decades, gymnastics fans believed that the judges raised Larisa Petrik’s prelims scores at the last minute to ensure a tie between Petrik and Čáslavská.

I debunked that myth here.

Who was the rightful winner?

The Mexican newspaper El Informador suggests that Kuchinskaya was scored too low, implying that she should have won:

The extremely difficult routine of Natasha was scored scandalously low, leaving her in third with a 19.650 for the bronze medal.

Los más difíciles ejercicios de Natasha fueron calificados escandalosamente bajos, quedando tercera con 19.650 puntos para medalla de bronce.

El Inforamdor, Oct. 29, 1968

Meanwhile, the Dutch newspaper Trouw thought that Čáslavská should have scored a 10.0, which would have made her the sole gold medalist.

Twice Vera had to return to the stage before the audience was willing to comply with the request for silence. The ideal rating of “ten,” which should have been given for this jewel of gymnastics, did not appear on the electronic scoreboard.

Tweemaal moest Vera terugkomen op het podium, eer het publiek bereid was gevolg te geven aan het verzoek om stilte. De ideale waardering “tien,” die voor dit juweel van turnkunst zonder meer gegeven had mogen worden, verscheen niet op het electronische scoreboard.

Trouw, Oct. 28, 1968

The Podium Protest

At the time, the Dutch newspaper Trouw wrote:

While the Russian national anthem was playing, Caslavska, who, along with her compatriots, had not been acknowledged by the Russians during the team medal ceremony, stood on the podium with her head turned away.

Terwijl het Russische volkslied klonk, stond Caslavska, dei tijdens de ceremonie protocolaire van de teamwedstrijd met haar landgenoten niet door de Russinnen was bekeken, met afgewend hoofd op het schavotje.

Trouw, Oct. 28, 1968

In other words, the writer saw Čáslavská’s gestures as a reaction to — or continuation of — what happened on the team podium, where the Soviet and Czechoslovak teams ignored each other, refusing to shake hands.

Here’s what Čáslavská said at the time:

“We must show the people at home that our hearts are with them,” said the pretty, 26-year-old Miss Caslavska, who repeated as the all-around women’s gymnastics champion of the Olympic Games.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 27, 1968

And here’s how Čáslavská recalls the story years later in Věra ‘68:

Side note: In 1966, Čáslavská was criticized for her podium etiquette. However, it wasn’t for political reasons.

The Price of Protest

In 1970, Čáslavská had the opportunity to distance herself from the Two Thousand Words manifesto, but she doubled down:

Czechoslovakia’s multiple Olympic champion in gymnastics, Vera Odlozilova-Caslavska, was reported today resisting pressure from the Prague communist regime’s thought-control campaign.

While many prominent personalities who signed the 1968 declaration “Two Thousand Words” have now disassociate themselves from it, “Vera Caslavska has confirmed her signature through a subsequent declaration,” reported the communist newspaper Nova Svoboda, received in Prague today from the city of Ostrava.

…

Following her refusal to disassociate herself from the declaration, Mrs. Odlozilova-Caslavska was refused permission to make an exhibition trip to Japan.

The Daily Yomiuri, June 25, 1968

That article only touches upon the ramifications for Čáslavská.

On April 9, 1990, the New York Times published a piece that chronicled Čáslavská’s life after the 1968 Olympics. It detailed her struggle to find work and the Czechoslovak government’s attempts to hide her from the public.

A day after her final event, she married a Czechoslovak 1,500-meter runner, Josef Odlozil, and returned home to start a family and complete her autobiography. But she found that the Government had not forgotten she had signed the manifesto.

She could not get her autobiography published, no doubt because 140 pages were devoted to how Czechoslovakia’s sports system worked and how Government officials treated athletes and sports administrators. In time, she had it published in Japan, but without the sections deemed unacceptable by the Czechoslovak Government authorities.

On Jan. 3, 1970,* she began another fight. She asked the Sports Minister, Antonin Himmel, for a job with the national girls’ gymnastics team. He refused, saying: ”Come back next year. This is not a suitable time yet.”

For five years, every Jan. 3, she appeared in the same office, asking for the same job.

”For the fifth year, I was supposed to apply again, but I knew it was necessary to change my way of negotiations,” she said. ”So I dressed in an aerobics suit, high at the neck, very tight. I am quite a conservative person, and it was hard for me to dress like that, but I had to look for my courage.

”Mr. Himmel looked at me and measured me with his eyes. He asked me: ‘Vera, what have you got on? Are you crazy?’ I answered him: ‘No, but I was supposed to come back on the third of January, and apply for work, and now I’m here, dressed for work. And I’m not leaving until you give me a team and a gymnastics hall in which to work.’

”He was not able to decide such a thing alone. He called all of his advisers into the room. A full 20 men stared at me. They finally decided I could get a team, but it had to be done in a very secret way.”

Denial Sought and Refused

To save face with their superiors, the sports authorities allowed Caslavska only to work with the current coaches. She would not be allowed to travel outside the country. In time, the authorities offered to loosen their grip if she would deny publicly that she had signed the manifesto. She refused.

Her absence from view lasted another five years, until 1979, when Czechoslovakia was trying to improve economic ties with Mexico. The Mexican president, Jose Lopez Portillo, remembered her from the 1968 Olympics, and asked the authorities if Caslavska would be permitted to come to Mexico to work with young Mexican gymnasts.

”I don’t want to say I was exchanged for oil,” Caslavska said, with a laugh. But she was allowed to go, and spent the next two years there.

Even after her return, however, the authorities tried to keep her hidden. On a 1984 visit to Czechoslovakia, the president of the International Olympic Committee, Juan Antonio Samaranch, asked to see her and Emil Zatopek, the distance runner who won three gold medals at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Samaranch was told that Zatopek was ill and that Caslavska had family problems.

A year later, Samaranch returned and insisted upon presenting Zatopek and Caslavska with the Olympic Order.

This time, the authorities relented, and from that point on, they were unable to deny her existence any longer. She was allowed to join the European Gymnastics Union as a representative of the country and become a full-time coach with the national team preparing for the Seoul Olympics.

A year later, when the Communists were ousted from control of the Government, she began serving as an adviser to President Havel on matters of health care, human rights, physical education and sports.

She recently represented President Havel in Japan, where she spoke to 150 business executives in an effort to generate more business for Czechoslovakia. When she returned to Czechoslovakia, the possibility of going back to Tokyo as ambassador came up.

She also knows how disorganized Czechoslovakia’s sports system has become. Before, everything was run from the State Central Committee for Sports. Now, each individual sports federation is on its own. The National Olympic Committee wants Caslavska to be its president.

When Communist rule ended in Czechoslovakia in 1989, new President Václav Havel made her his adviser for sport and social issues. She led the Czech Olympic Committee from 1990 to 1996, and she was a member of the International Olympic Committee between 1995 and 2001.

The New York Times, April 9, 1990

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

For clarity’s sake: Someone might read the article from the New York Times and think that Čáslavská landed in Czechoslovakia after the Olympics and disappeared for several years. It wasn’t quite that simple.

For example, in 1969, she traveled to the United States to accept the Woman Athlete of the Year at the York, Pennsylvania Area Sports night (New York Times, Feb. 1, 1969). (There was a large Czechoslovak population in Pennsylvania.)

She was allowed to publish an article on gymnastics.

She appeared at the 1972 Munich Olympics — as seen here:

And when she was in Japan in 1977, she was asked about Comăneci’s performances. Here’s what was reported:

Vera Caslavska, the retired gymnastic queen of Czechoslovakia, said Saturday that women’s gymnastics has become something like circus stunts.

Speaking to newsmen, she said that as a gymnastics coach she was worried that young female gymnasts were now required to practice techniques that might impair their physical growth.

Therefore, Caslavska said, she did not want her 8-year-old daughter to become a gymnast.

Caslavska, 35, gold medalist in the 1964 and 1968 Olympics, has a rather critical view of Nadia Comeneci, the reigning queen of gymnastics from Romania.

She said the young Romanian, in winning the European title in May, displayed only the same techniques as in the 1976 Montreal Games. “She will not be able to remain No 1 if she keeps doing the same things,” Caslavska said.

Caslavska arrived in Tokyo Saturday for a 11-day visit to Japan.

The Daily Yomiuri, August 28, 1977

(This, by no means, is an exhaustive list of all the Čáslavská appearances. )

But, by and large, for an international sports star, Čáslavská was hidden from the public eye. You can watch Čáslavská talk about her experience in the second half of Věra 68.

It should be noted that Čáslavská wasn’t the only athlete to protest at the Mexico City Olympics. U.S. sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists during the national anthem at the medal ceremony for the 200 meters. Avery Brundage, the President of the IOC and an American himself, reportedly called it, “a nasty demonstration against the United States flag by negroes” (Guttmann, The Games Must Go on).

The two athletes were expelled from the Games, the White House declined to host them, and the FBI monitored them. Contrary to popular belief, they did not have to return their medals.

Note

Before I start the history of the next quadrennium (1969-1972), we are going to take a detour and travel back in time to 1948. We’ll take a look at the first Olympics after World War II, the emergence of the Soviet Union, and the defection of a Czechoslovak gymnastics icon.

If you’re a gym nerd, you’ve probably heard of her, but you might not know the full story and how gymnastics contributed to her defection.

2 replies on “1968: The Women’s Event Finals in Mexico City”

FYI – better quality coverage (with real sound) of the Women’s Event Finals from TV is available here: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x4rtbqn_1968-olympics-gymnastics-women-s-event-finals_sport

Excelente artículo. Me encantó. Ambas hicieron una hermosa rutina de piso.

Creo que la decisión fue muy sabía.