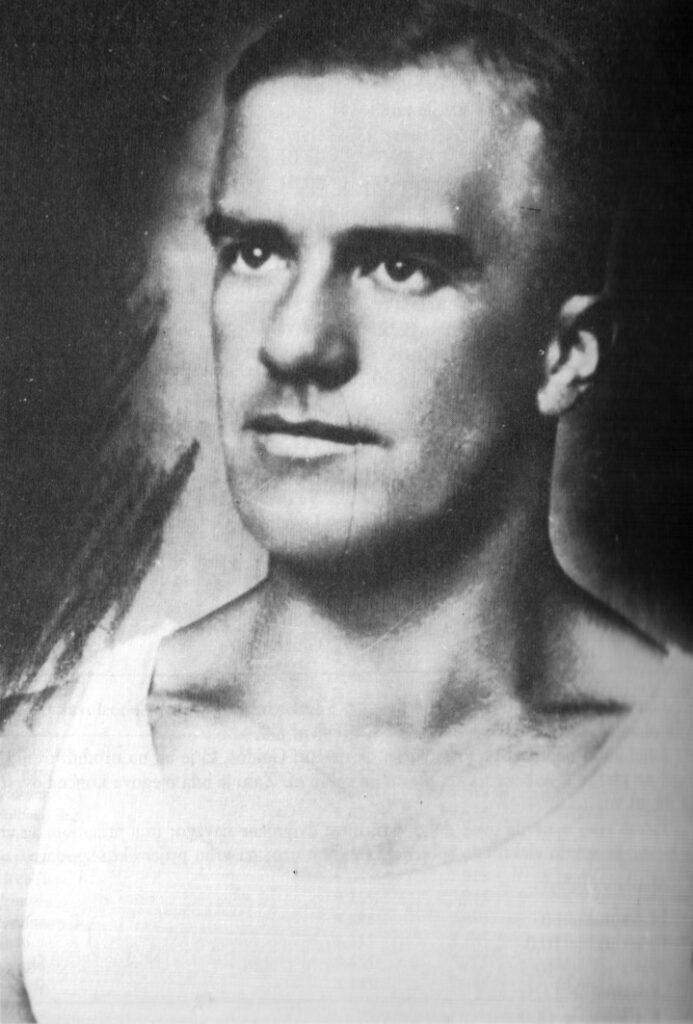

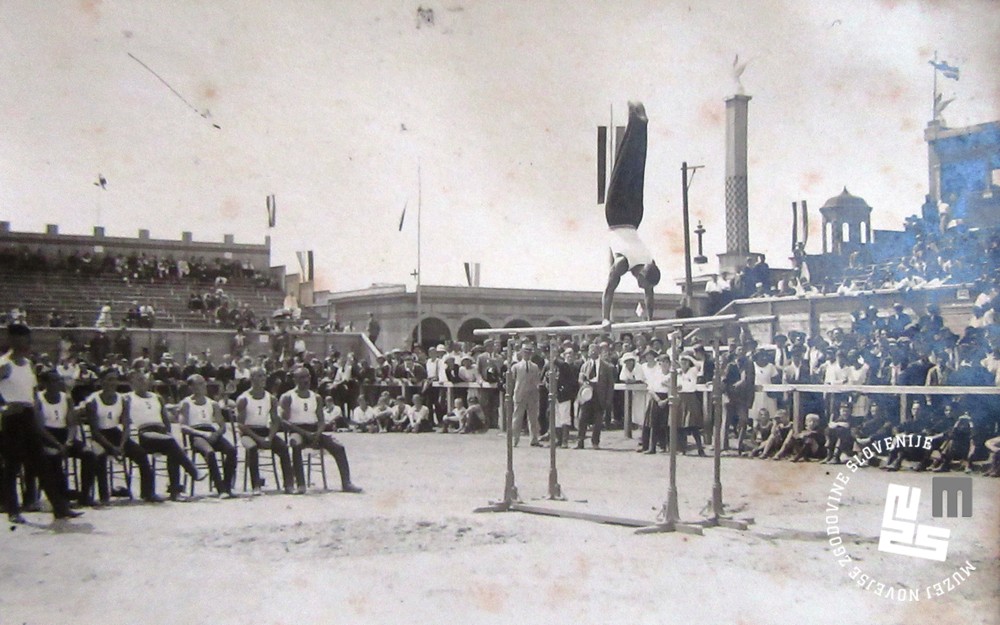

During the first day of the 1930 International Tournament, Anton Malej fell from the rings and later died in the hospital. His injury happened on a rather simple skill: an inverted hang. Here’s how Pierre Hentgès, Sr., recalled the injury:

On the rings, during a simple part — an inverted pike hang — the young Yugoslavian gymnast Anton Malej fell so badly that he had to be taken to the hospital immediately for professional treatment with a cervical vertebrae injury.

Olympische Turnkunst, December 1967.

An den Ringen, in einfachem Übungsteil aus dem Sturzhang, fiel der junge jugoslawische Turner Anton Malej so unglücklich, daß er sofort mit einer Halswirbelverletzung zu fachgerechter Behandlung ins Spital überführt werden mußte.

What follows is a translation of Malej’s obituary from Sokolski Glasnik (July 15, 1930).

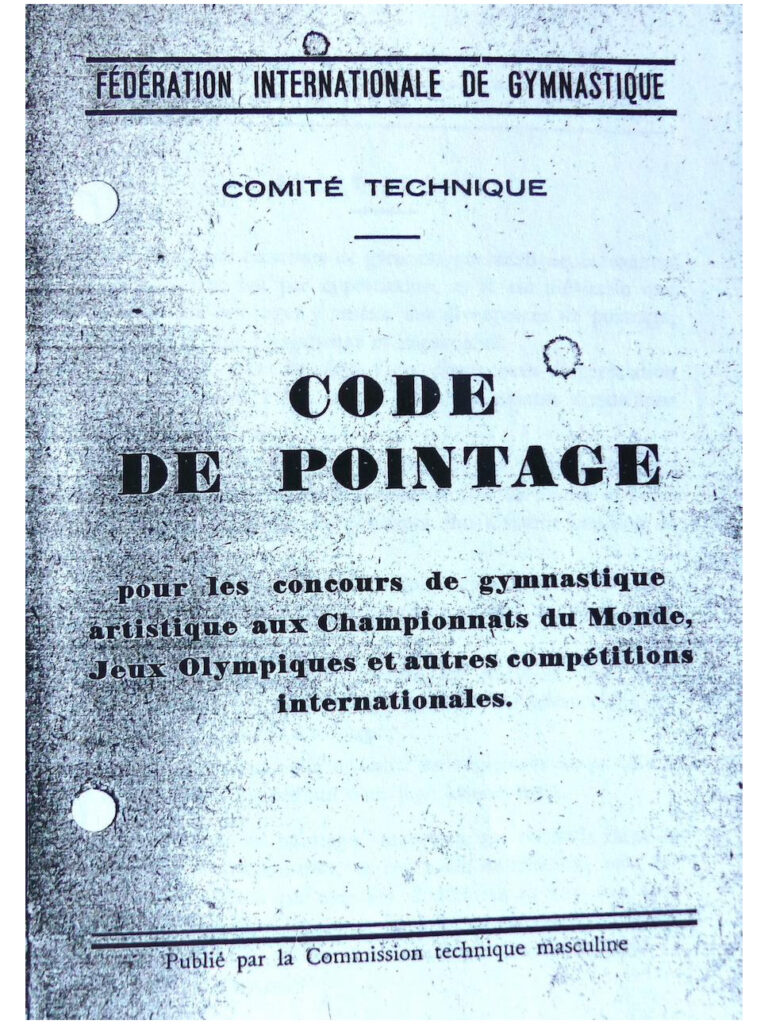

To read more about the 1930 World Championships, head over to this post.