What’s it like to try to defend your Olympic all-around title? At the time of this writing, only two female gymnasts have done it: Larisa Latynina (1956, 1960) and Věra Čáslavská (1964, 1968). Many are betting that Simone Biles will become the third.

Below, I’ve translated a portion of Čáslavská’s The Road to Olympus (1972), in which Čáslavská recalled her quest to defend her all-around title in Mexico City. She discussed everything from the inane questions of journalists to rivalries to intimidation tactics to nerves to bad lighting in arenas to difficulty adjusting to the bars during podium training.

Enjoy this excerpt from her book!

El Grand Duello

[Note: This is the spelling used in the book. The correct spelling in Spanish would be El gran duelo.]

Many are rooting for me, many for Kuchinskaya. Mexican newspapers have been running countless sensational stories and hoaxes, including the news that Natasha Kuchinskaya has been kidnapped by Czechoslovaks and has been missing for several days. But they maintain the etiquette of combat, the rules of fair play. It has not happened that one of us has been unreasonably despised.

I think Mexicans are far more committed to justice than any other people. Their sense of justice is — one might say — as innate as their temperament, their openness, and their uncompromising nature. And that is why they give Kuchinskaya just as many votes as me, the same opportunity to make themselves heard. Watch out!—I say to myself at every turn. You have to be better than you think because they expect you to be. But neither today nor tomorrow must you reveal your cards. Nor the day after tomorrow. The time is yet to come.

The Auditorio Nacional is largely full. Even though it is an ordinary training session, the Mexicans found enough time to see for themselves how Věra and Natasha are doing.

It was beneficial to go through this familiarization training. One must learn to understand the mentality of an audience trained mostly by soccer games and corrida. And whoever does not allow themselves to be stifled by the manifestations from the auditorium, whoever does not let their breath be knocked out of them at the first onslaught of the shouting of various names by many voices, whoever does not allow themselves to be unnerved by not hearing only their own name called out, as they were used to, or perhaps as they expected, has won.

The Auditorio Nacional during the public practice, when we were both on stage at one point, strongly resembled a corrida – a clash between a bullfighter and a bull. Only sometimes you didn’t know whose role you were in.

At the moment when I finished performing on the apparatus, a loud and many-voiced chanting of Věra-Věra-ra-ra-ra broke out, and the next moment, when Natasha finished performing, the hall roared in the same strength and size — Natasha-Natasha-ra-ra-ra. It was a very unusual feeling. In the beginning, I felt like giving up this fight for the audience’s sympathy.

But Mexican joie de vivre is contagious. It didn’t take long before I started having a lot of fun, too. When it’s fun, it’s fun. I did some major exercises that Slavka and I had kept under wraps for a long time. The audience was hooked; the enthusiasm was never-ending. And once again, Věra-Věra-ra-ra-ra was on the show. But the next thing I knew, they were cheering for Natasha again: Natasha-Natasha-ra-ra-ra. Yes, my dear—I think to myself—this is not going to be easy. So who? The bull or the bullfighter? But who’s really who? Finally, that’s not important right now. The important thing is to leave the arena as a winner.

“Věra-Věra-ra-ra-ra, Natasha-Natasha-ra-ra-ra,” the audience roars, eager for an exciting spectacle.

Why not? If they want it they should have it. I’ve got some more trumps, no worries! I’m curious to see how impressed I am with my full-twisting hecht from the high bar over the low bar.* What about Natasha? How will she react to us not doing the same end after all?

[*Note: Čáslavská did not compete a full-twisting hecht in Mexico City. Rather, she performed a straddle hecht from the high bar over the low bar.]

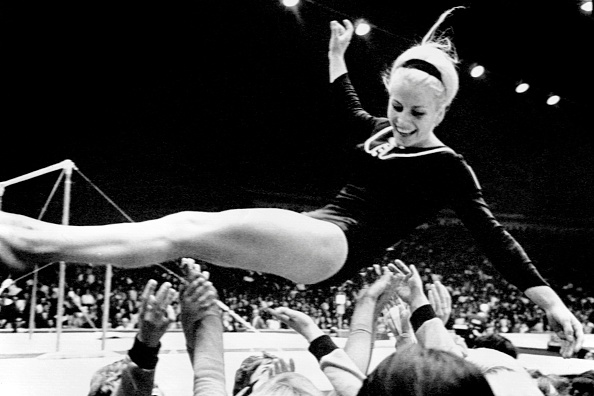

Slávka [Matlochová, Čáslavská’s coach] is already standing under the bars, ready to give me a rescue, just in case… A pop, a swing, a bounce and… The auditorium was buzzing with excitement. I landed five meters behind the bars, the audience erupted in cheers.

I waited until the hall calmed down a bit—and now the bars are mine again. A sharp bend over the high bar, a dive headfirst to the ground, my arms just like that without support… I think I’m going to break my neck. I was really in trouble. At the most extreme moment, I grabbed the low bar. The audience was speechless with astonishment and then, as if in ecstasy, they shouted bravo, bravo, Věra-Věra-ra-ra-ra-ra-ra and applauded in syncopated rhythm.

I thought this was really funny, even though my health was almost certainly at risk. I’ve never performed in the midst of such excitement before. You’re tempted to take chances.

But the best was Slávka Matlochová. When I was resting, she sat down on the bench next to me and started reporting the corrida with a fantastically funny face. I didn’t know Slávka was such a comedian.

“Stop at the top, Mrs. Chaslav. Go home!” she said contentedly. I bowed to the still chanting audience and thanked them for their support. What happened next in the hall, I don’t know. When I was in the dressing room, the audience was already shouting “Natasha-Natasha-ra-ra-ra” again.

*

I had a press conference in the evening. The Mexicans had prepared questions about the body:

– There are rumors that you will defend your Olympic victory from Tokyo after all. Are you convinced of that yourself?

– Dear Sir, you may not be satisfied with my answer, but I never count the chickens before they hatch!

– I was fascinated by your Věra-flip on the bars. But aren’t you worried that once you miss, you’ll lose your beauty?

First of all, I was amazed at the original title. Slávka and I couldn’t think of any suitable name ourselves. I only know the flip from acrobatics on the ground—it’s a kind of backflip. A flip on the bars, then? Yes, it is. Why not? We didn’t think of it! Please, and this gentleman is not a gymnast or an expert, just an ordinary journalist.

– That I’ll lose my beauty? Oh, thank you for the compliments. I knew Mexicans were gentlemen. From now on, I’ll be more careful with myself.

And then there was one question after another: How about you getting married? Will you continue to head toward marriage after the Olympics? What do you think of Kuchinskaya? Your plans for the future?

[Reminder: Čáslavská married track athlete Josef Odložil in Mexico City. The couple divorced in 1987.]

The allocated time had expired. I managed to walk briskly and swiftly to the boarding house, sign my name to many of the boys, exchange a few pleasantries with the director of the girls’ village, but that was all for that day. I was dead tired.

BLOOD CELLS ARE GETTING ALARMED

“Vra, get up! Open your eyes!”

The eyes don’t want to. Just a minute, just a moment, let me dream. It’s five o’clock in the morning, and today, like yesterday, the day before yesterday, and all the days before, she is laboriously getting me out of bed. Getting up early in the morning is my biggest problem. Ever since I was a little girl.

A few more days and then I’ll sleep for a fortnight and no one will wake me up.

We were supposed to go all out first. To see if the red blood cells would not get too alarmed in the high altitude.* But Mirka got injured, sprained her ankle massively. And poor Marienka has inflammation in her leg and a temperature of thirty-eight degrees Celsius. Little Hanka is begging for a headache pill. Bohunka’s thoughts are elsewhere, only Hanka “Vorlik” saves her honor and reputation. The picture of our seven is completed by yours truly (in Latin: leucojum, the pale flower). A team to behold!

[*Reminder: Mexico City is 7,349 feet or 2,240 meters above sea level. The highest point in Czechoslovakia would have been Gerlachovský štít (in present-day Slovakia) at 8,709 feet or 2,654 meters, but no gymnast would be training on Gerlach Peak.]

Strangely enough, even Slávka is sympathetic to us today. She’s not angry, she’s just a bit grumpy that we won’t be in the best shape. What can I do, I’ll get on with it. Someone has to start. — “Ruda,* please, but don’t chase me so much, let me breathe a little during the waltz.” — “Well, Věra, if you want, I can play you Cemetery, Cemetery… “**

[*Ruda was the team’s pianist. She has a funny anecdote about him and stinky cheese in her book.]

[**You can listen to “Cemetery, Cemetery, Garden Green” here.]

Mexican Rhapsody—first time in Mexico. What impression will it make on us? Fortunately, there is no public training today—the twenty people in the hall is quite a sympathetic number that allows you to see where you are at without too much scandal.

Ruda started playing…

I had a great time performing. I could feel the Mexicans’ attention. The music was literally going through their bodies. Halfway through the routine, they started clapping. I was good until then. But shortly after the halfway point, the break came. I had to interrupt the routine and mask it as if I was deliberately only going through separate parts. I didn’t even have the strength left to walk off the carpet like it was nothing. My arms and legs were numb, I couldn’t catch my breath, I had a beautiful purple color. Immediately Dr. Macha came running up to me with his mobile pharmacy, a small wooden case, and took my pulse. “Two hundred and four a minute. Oh, dear! Věra, I don’t recommend you to be so frantic. Take it easy, piano. “Doctor, have you ever seen a Mexican rhapsody practiced calmly?”

The door opened, and the Soviet gymnasts came in. They weren’t supposed to train today. We were surprised, why deny it? Suddenly we were all healthy. My original color returned, Mirka bit her lips and bounced to the compulsory bar routine, Maricka and little Hanka jumped somersaults, Bohuna started to get ready for the optional floor exercise. “Hail the queen—Bohuna is not normal,” said little Hanka. Ruda preluded, played a few opening chords… Bohunka is holding up superbly! All respect.

Ruda’s long-time colleague Ivan Ivanovich, the pianist of the Soviet gymnasts, sat down at the second piano (the Mexicans were so comfortably equipped that in some gymnasiums they had three or four pianos) and started a somewhat familiar march. The Soviet girls marched onto the carpet and Fučík’s March of the Gladiators was inserted into Dvořák’s New World Symphony—I know it now. It was an original gesture and Bohunka had a reason to leave the carpet early. Who knows what the blood cells would say?

We gained valuable experience with today’s training. It’s not possible to do the whole floor exercise in such a hard way. That’s just a killer. Easy and slowly, as Dr. Macha says, the body is not ready for such a load. Never mind, tomorrow we’ll start again from the start, in quarters, then in halves, slowly but surely, it always pays off. And in four or five days, we’ll get started. Mexican Rhapsody awaits its premiere.

BE HAPPY, MAN!

Pepík and I complement each other very well: Initially, we were both worried that—although we were trying hard—we would do more harm than good. It’s not so easy to be on fire and scream that it doesn’t burn you when you have some worries, nerves, disappointments, and disillusionment every day. A person, oversaturated with daily impressions, needs to react somehow.

And who better to confide in than a close one? Like me, Pepík has his moods, and no pre-race fever could be without them. But fortunately, he knows how to deal with them much better, in a tougher, manly way.

The closer the competition gets — but not only mine, the worse it gets for me. No one would believe what a nervous wreck I can be, and most of all, how confused I can get. I can alarm everyone around me so perfectly before a competition, they almost believe I can’t do anything. I don’t even know why it always comes out like that — maybe it’s a way of relaxing. But I can be most calm when everyone else is alarmed.

And because Pepík has such a hard time with me, because he has so much understanding and patience for me, because he serves as the hollow willow tree that I can talk to any time that I need so much to calm me down, I want to help him somehow. I go to the stadium with him every day to time him, to cheer him on. And encouragement is needed like salt here in this ungodly high altitude. I wouldn’t change him at all — just the memory of yesterday’s floor exercise gives me the creeps. And the floor exercise is only ninety seconds of intense exertion.

“So it seems to me that you’re running kind of hard today. Would you like to stretch your body a bit?” I say as he comes over to the bench to get a towel.

“Oh, doctor, watch what happens when a woman gets involved!” he complained casually to Dr. Fischer. The latter smiled indulgently and tapped Pepík on the shoulder, “Be glad, man!”

“Really, Pepík, let me tell you. You know very well that Clarke* does gymnastics training too — I saw him yesterday with my own eyes — he was splitting his legs up to his ears!”

[*This is most likely a reference to Ronald William Clarke of Australia, who took bronze in the 10,000m in 1964.]

“Věra, are you exaggerating again? Tell that to the pigeons, not me. Clarke and legs up to his ears! Who ever saw that? It must be some kind of oversight — Clarke’s quite a decent man, not a gymnast. So don’t slander him!”

“Pepík,” says Dr. Fischer, “maybe it’s not so silly. There are special exercises that stretch the muscles perfectly. But they must be done every day.”

“Well, that’s it, doctor! That’s the kind of exercises I know, really,” I seized the opportunity, and happy to be of some use, I persuaded Pepík to sit down on the floor.

“For me — I’m done for the day anyway,” he waved his hand and sat down resigned on the grass.

The first time since we have known each other, he listened to me. When I bent him down, a strange cracking noise came out suddenly. He hissed in pain and crawled to the bench. He was white as chalk.

Oh, my God, I messed up again! If he has a torn muscle, it’s over. I immediately started reassuring him that it wasn’t serious and talked a lot. “I’ve had so many torn muscles! And I’ve done somersaults with them,” I waved my hand casually, as a sign that it wasn’t worth mentioning. But I felt like crying. I know best what the slightest injury, fear, insecurity means to an athlete. And also — he will now have to go off for a day or two. A day or two of the most precious training. I’d rather receive a few slaps than this.

WHY?

For the second time in the Auditorium! Last time before the competition.

“So Věra, be cheerful and smart! It’s about to get tough.”

“I know. Corrida again… “

“Please, if anything happens to you, don’t give in to your melancholy! That would be the grave.”

“I obediently declare, Mrs. Matloch, that I shall not fall into my own or any other man’s melancholy! I have already freed myself from everything and have got the irritating red color for my leotard,”—I try to turn the conversation into a joke, for I feel a chill running down my back again.

*

“Věra-Věra-ra-ra-ra,” the hall welcomed me again. Natasha was not left out either. I looked for her on the stage among the Soviet gymnasts. In vain. At one of the countless calls of “Natasha-Natasha-ra-ra-ra” a fair-haired girl stood up near us. She waves to the audience.

Why isn’t Kuchinskaya training today? Does she want to peruse me in peace and quiet? Just to kill her last chance to get a proper feel for the competition environment?

You wouldn’t believe how big a role space plays in the exercise on the apparatus. It only takes an unusual ceiling height and one has to look for a more accessible landmark. And the lights? They can raise hell! Especially on bars. The bars fade quite a bit in the harsh light, you have to rely mostly on instinct. You practice by memory — gymnasts don’t like it that way. The bars are a chapter unto themselves. If they are attached to a more flexible floor — and the Mexican podium is flexible as hell — they immediately move differently, give different impulses than you’re used to. Or the bars! Too soft a bar is not suitable for an explosive, dynamic type of athlete. She has to wait a long time for every movement, deliberately slow down. Those who can’t make friends with the bars before a competition, those who don’t estimate what they are capable of, can get hit by them really badly. And also the hardness of the springboard! Knowing exactly the best place to bounce. Some springboards catapult you so fantastically that it is then an art to be able to steer yourself in flight to catch up to the horse. Other springboards, even with the strongest bounce, can’t return the inserted energy. And so it is with every apparatus, carpet, bar, or beam, everything has its glitches.

And that’s why we have these get-to-know training periods and why I’m confused that Kuchinskaya is ignoring the option.

But why?

That leaves the second option: that Kuchinskaya is so perfectly prepared that there is no need to try the apparatus.

It makes me nervous.

Kuchinskaya stayed in the stands until the end of the training of her orphaned teammates. We finished shortly after them because other participants were already waiting.

When we were returning to the village on the Olympic bus, they sat right behind me. Kuchinskaya and her psychologist.

They laughed and talked, chattered, and, most importantly — laughed and laughed. I understood that they were not afraid. But I was! I made it more than spectacularly clear.

Then I met our boys, the gymnasts, in the village. And so as the water runs and talk is made, the talk turned to our public training. I made no secret of my concerns. And then one of the boys told me something I hadn’t thought of before: “Věra, she’s afraid of you.”

THE GAME

And then things began to move quickly. With the start of the Olympic competitions, time was given wings.

Pepík is counting down the start of the race only for hours, he will have to start the race in the afternoon. I’m sick to my stomach.

“Do you need anything? Do you want some vitamins, fruit, or a massage?” I offer him my services, but he doesn’t say anything, he says he can do it all by himself. So I don’t get distracted and nervous. He’s getting less and less talkative as the race gets closer, I’d like to do the 1500m race instead of him.

“You’re not going to the stadium, you understand! Not even secretly! And I’d like you to ignore the TV coverage, too.” Then he came up with an idea that I liked. It was so childish. “You’ll wait in the village, you won’t find out anything, I’ll tell you the result myself. Deal?”

So I obediently waited at our agreed place, but it was worse than anyone would have thought. The hour and a half took forever. But all things must come to an end, the bus brought the first athletes… From a distance, I saw him run around the corner of the building and jump over the railing. I could tell right away that he had advanced. But then he saw me, and he slowed down and walked with a sad, sad face. I didn’t want to spoil his boyish joy:

“So? How did you do?”

“Badly… ” He leaned dejectedly against the railing. His face was drawn, his eyes sunken, and he was bland.

“Actually, I had a bad run today … “

Maybe he didn’t actually succeed…

I’ve succumbed to real skepticism… He couldn’t take it and started laughing. Oh, come on! I knew right away.

The next day we were in the semi-finals, and we had a similar agreement … However, a coincidence intervened in the scenario of our game in the form of Bohunka. She came to tell me that she had seen on TV a while ago that Pepík had advanced again. I was happy, our shared wish — to be in the final — came true. I was allowed to go to the finals after that. But I guess I’m bad luck to others. That Keino and his friend Jipcho were running like someone was screaming bloody murder, not even the fantastic Ryun could keep up. I was sad for Pepík…

[Note: Ken Keino of Kenya won the 1500 in Mexico. Ryun, the world record holder from the United States, finished second. Odložil, Čáslavská’s soon-to-be-husband, finished 8th, a disappointing finish for him since he took silver in 1964. Ben Jipcho of Kenya finished 10th.]

LAST TIME

So today for the last time…

In an hour, the Olympic bus will take us to the Auditorium National and there my last competition will begin. My last Olympics.

How many times has this uneasy feeling come up? This uncertainty? And nerves! Two more days, three with the final competition, and it’s over. Once and for all. The repetitive, yet always different, will be over. Today, tomorrow. Maybe the day after tomorrow…

The time was up, the evening had come. The Auditorium Nacional was lit up with a thousand piercing lights, the seats filled to capacity. Gymnastics has become a highly attractive affair for Mexicans, and few are willing to volunteer to spend the fight for Olympic gold in front of the TV only.

Poor Pepík! He stayed outside and it was beyond my power to get him inside. The promoter was adamant. After a long, arduous explanation, he understood, saluted smartly and the situation was saved. Pepík’s presence always makes me very strong in competitions. And how could it not! Perhaps every girl wants to show off a little in front of her boy.

The start is inevitably approaching; the judges are sitting at their tables, the counting committee seems to be fully ready.

Eighteen thousand spectators and silence like a church… Here and there a seat creaks in the auditorium; someone coughs stifledly. Such a strangled mood that doesn’t bode well. Full of tension.

The organizer lines us up in a dark, uninviting corridor in a four-way line. Everything that until yesterday seemed nice and fascinating is now unwelcoming and black. How is it possible that I have allowed myself to fall into such a ‘gloomy mood’?

I am nervously pacing, every now and then raising my hands or pausing to check that these or those parts of my body really belong to me and that they have not yet completely obeyed me.

Final preparations and inspection. The Soviet athletes are standing in a closed circle and listening attentively to their coach Sofia Muratova. They’re ahead of us by a slim margin and we’re determined to do all we can just to hold on to our World Championship title in Dortmund. At the results ceremony—as silver medalists—they congratulated us with the addition:

“Only to Mexico!”

[Reminder: The Czechoslovak team defeated the Soviet team in 1966.]

There was a fanfare, then the Olympic theme song. The dressed-up military band started marching.

My throat constricted and a strange chill spread around my stomach.

This competition will take two hours. T w o l o n g h o u r s… In the whole of life, that’s a drop in the ocean. And yet, sometimes this time means so much.

We are unable to catch up with the Soviet gymnasts in the team competition. No matter how hard we try, the vision of a medal is slowly but surely melting away. Before the last event, the uneven bars, it’s clear. I have no choice but to do my best to make sure that the hope for gold in the individual event is not wasted either. I have a double responsibility and it’s hard. Extremely difficult.

“…we take turns with Vitek Matlocha in describing the individual exercises and wait for the arrival of Věra Čáslavská.

I accept the microphone and they focus on one thing: “keep Věra Čáslavská on the uneven bars. On tricky bars that can be risky and can mean defeat. Not that we don’t trust Věra, no. But she has a number of difficult elements in her routine that can cause a fall.

We remember well the World Gymnastics Championships in Prague and Věra’s accident on this apparatus that cost her the gold medal. At the same time, we know that if our gymnast can perform on this apparatus with any average performance, but without falling, she will become an Olympic champion.

Věra knows that we are broadcasting home, to Czechoslovakia, she knows that one single wrong move can disappoint millions of listeners who are awake and dreaming at this moment.

Věra slowly, one could say even timidly, steps on the podium, presents herself to the judges … She stands in front of the uneven bars, in front of the last discipline of her journey to the Olympic title… She has lowered her head to forget the world and become the instrument of a single will. She raises her eyes from the ground, looking intently at the bars. One second… two… three… It’s as if at this point, she’s not even a normal human being, accessible to the perception of her surroundings… Her usual complexion has turned green, two deep chasms instead of eyes, without a glimmer of life, only the darkness of desperate inhuman concentration for a few tens of seconds; to come.

She took a deep breath… She steps out, bounces off the springboard, flies through the air, already on the lower bar, does a quick spin forward… One loop, second loop, exercises on the bar, leaves it, risky full turn… falls to the lower bar…

My God, she didn’t fall!, I shout into the microphone and a huge boulder falls from my heart. I repeat, relieved:

She didn’t fall, she didn’t fall.

I will probably never forget the moment when Věra left the upper bar of the bars to turn into a space flyer, who is not subject to the weight of the earth. Nor will I ever forget the “My God” that slipped out of my mouth in a moment of excitement. Nor the most wonderful moment an athlete, spectator and reporter can experience when the Czechoslovak national anthem is played over the sports field. Can there ever be a happier moment? And does a reporter even have the right to change in that moment from a slick, handsome, above-it-all man of beautiful words to an ordinary Czechoslovak fan who tears up like those around him and who sings the Czechoslovak anthem in a hoarse, tired and false voice?”

Czechoslovak reporter of the XIX Olympic Games

Karel Malina

A sprig of laurel, a touch of gold medal on a burgundy ribbon… The certainty that no one will ever take it from you again.

But a few hours ago?

I felt like a little ant, who is putting straw to straw — and yet with one mistake, his construction can collapse. I checked off one apparatus after another — first balance beam, then floor exercise, even vault. There was one last, decisive round left – uneven bars. I had the gold medal in the all-around, the most valuable and most coveted, within my grasp. But it only took one wobble for my hopes to collapse like an ant’s building. At times like this, it’s no longer just physical readiness that makes the difference…

[Reminder: At the time, there wasn’t an all-around final. The all-around champion was declared at the same time as the team champion, after compulsory and optional. Also, Čáslavská does not mention that Kuchinskaya had fallen during her compulsory routine on uneven bars and, in effect, took herself out of contention for the gold medal. Kuchinskaya was able to climb her way back to a bronze medal in the all-around.]

The first two days of the Olympic battles are happily behind us—the final competition on individual apparatus remains.

I am the only one competing in all four disciplines. Today, however, I feel incomparably better than yesterday. I’m like, “I will, I will, I won’t, I won’t. But that’s just to push away the gloom, the stage fright and the fear that comes up every now and then and tells me that I can’t defend yesterday. In the corner of my soul, however, the worm of Mrs. Matlochová is also beginning to gnaw at me: ‘Mrs. Čáslavská, I have a feeling… Four medals! Remember? That damn four won’t leave me alone—it’s still haunting me… I have a strange chill down my spine—a kind of primal feeling. I’m looking forward to it!”

Suddenly she was there and she winked at me. Ceremoniously and with recorded importance, she lined up four porcelain pigs next to me, on the competition bench.

The first discipline was vault, I’m the last to get on, a perfect situation for me. There’s nothing stopping me from vaulting the best I can. It’s the last time!

The indicator light says 9.90 the first time, 9.90 the second time.

I’m getting my first gold of the night.

I’m up third on uneven bars. I get another 9.90 and the military music plays our national anthem again.

…remembering Mommy, Daddy…

Also Eva Bosáková.

[Reminder: In addition to being a legend of Czechoslovak gymnastics, Bosáková was Čáslavská’s first coach.]

I also remember the coach Vladimír Prorok. If only he knew that I sent him congratulatory telegrams with fictitious names after the famous Tokyo Games! I was sorry he was forgotten in all the glory. After all, he deserved the same admiration and recognition as I did. Few people realized at the time that there was also a piece of his honest work in all this.

Or the doctor from the Stresovice hospital, Dr. Eiselt! Where would I be today without his help! And also the optimism of the psychologist Dr. Vanek, the care of our masseur Dr. Stejskal.

And finally, Slávka! She is deservedly reaping her fruits. She’s happy…

Memories are more and more attached to home, to people who wrote me nice letters, shook my hand encouragingly, smiled when they met me… I thank them today too, because I have never been so brave as to look for strength only in myself.

It’s time to say goodbye. Tonight, I’m putting away my gymnastics leotard forever. Tomorrow I’ll wear my wedding dress. I used to go to the closet to look at it in my most tired moments. Dreamily, as all brides do. There’s so much in me already. I long so much for peace, for rest. For a fairly normal life of simple people, to have children and ordinary family happiness.

Twice for the last time today. Both as a representative and as Věra Caslavska.

“… today a bride, tomorrow a woman…”*, Slávka sang, breaking me out of my pleasant reverie. She dryly stated that she was going to the balance beam.

[*These are lyrics from the song “Ej od buchlova větr věje” (“Hey, the wind is blowing from Buchl”).]

The clock says 20 hours, 20 minutes.

At this point all reverie is there, there is again only a narrow strip of wood that came alive. From somewhere in the distance comes the melody of the Farewell Waltz,* creeping into my consciousness and carrying me away from the stiff judges, from the counting machines, from reality. I’ve practiced like in a dream… It was my most powerful experience in recent times, and as it turned out, it also swept away the audience.

[*”Valčíku na rozloučenou” has the same melody as Auld Lang Syne. You can hear a version here.]

The 9.85 score is received by the audience with a storm of disapproval. The judges sit at their tables with the flag as a banner of honor and justice. The announcer calls for quiet and the hall falls silent. Everyone waits for the last athlete, Natasha Kuchinskaya. She’s nervous too. She’s performing tentatively today, so she doesn’t fall during the pirouette. 9.85 is the indicator. Natasha Kuchinskaya has won!

After the silver beam—floor. My favorite discipline. I perform last, pretty much at the end.

My Mexican Rhapsody belongs first and foremost to the Mexicans. I want to thank them for their sympathy, for the appreciation with which they have accompanied me throughout the competition, but above all, I want to thank them for the immeasurable sense of justice that moves me so, so much. There are times when words fail, when feelings can only be expressed through music, singing, or dancing…

The dramatic piece ends. My whole body, my hands, and my face, I’m glued to the ground. I end up curled up in a ball…

The agitated silence turns into endless cheers.

The lights in the hall have gone out, the little thread will not unfurl.

I’m getting gold on floor exercise too. My fourth gold of the Olympics.

[Note: She tied for Larisa Petrik of the Soviet Union for gold. In her autobiography, Čáslavská does not mention her protest, but in a film about her performance in Mexico City, she discusses it. You can see a clip below.]

It’s a nice feeling—to win!… Flowers, handshakes, congratulations, photographers… It’s so easy to smile at the moment, the tiredness, the exhaustion, the thousands of difficult moments and millions of doubts, the endlessness of all the days and sleepless nights of waiting, it’s all finally over. I am standing on the top step, the red and blue flag rises to the vault of the hall, and everyone listens to our anthem with me.

Where is my home…*

[*The phrase in Czech is “Kde domov můj…,” which is a reference to the national anthem of the Czech Republic.]

After the competition, it will be written that it was a great drama. Mine, the internal one, was not complicated.

I wanted to win, and I had to win. I wanted to be first because I knew it wasn’t just about me.

Addendum: Čáslavská’s Protest from the film Věra ’68

More Excerpts from Autobiographies

One reply on “Čáslavská on Defending Her All-Around Title in The Road to Olympus”

Thanks for sharing this! I really enjoyed it!