On Wednesday, October 23, 1968, the Olympians in women’s artistic gymnastics competed in the optionals portion of the competition. As far as gold medals were concerned, there weren’t any surprises. The Soviet team was leading after the compulsories, and they ended up with gold. Čáslavská was leading the all-around after compulsories, and she won gold.

But the competition had its fair share of drama, especially on the podium. Let’s take a look at what happened.

Results | Judging Assignments | Skills Competed | Competition Notes

Results

Reminder: There wasn’t a separate team final or a separate all-around final. Both the team medals and all-around medals were determined on the same day — based on the compulsory scores and the optionals scores.

Here were the top 5 teams after compulsories:

- Soviet Union – 191.15

- Czechoslovakia – 190.20

- East Germany – 189.40

- Japan – 187.10

- United States – 185.70

Here were the top 5 individuals after compulsories:

1. Čáslavská, TCH – 38.85

2T. Voronina, URS – 38.35

2T. Petrik, URS – 38.35

4. Janz, GDR – 38.25

5. Zuchold, GDR – 38.20

Final Team Results

| Country | Rank after Comp. | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Soviet Union | 1 | 191.15 | 191.70 | 382.85 |

| 2. Czechoslovakia | 2 | 190.20 | 192.00 | 382.20 |

| 3. East Germany | 3 | 189.40 | 189.70 | 379.10 |

| 4. Japan | 4 | 187.10 | 188.35 | 375.45 |

| 5. Hungary | 6 | 184.75 | 185.05 | 369.80 |

| 6. United States | 5 | 185.70 | 184.05 | 369.75 |

| 7. France | 7 | 182.85 | 178.90 | 361.75 |

| 8. Bulgaria | 10 | 175.80 | 179.30 | 355.10 |

| 9. West Germany | 8 | 177.95 | 176.70 | 354.65 |

| 10. Poland | 9 | 177.50 | 176.35 | 353.85 |

| 11. Canada | 11 | 171.75 | 171.65 | 343.40 |

| 12. Norway | 12 | 167.50 | 170.65 | 338.15 |

| 13. Cuba | 14 | 153.10 | 169.75 | 322.85 |

| 14. Mexico | 13 | 156.45 | 154.80 | 311.25 |

Final All-Around Results – Top 20

| Gymnast | Country | Rank after Comp. | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 1 | 38.85 | 39.40 | 78.25 |

| 2. Voronina | URS | 2T. | 38.35 | 38.50 | 76.85 |

| 3. Kuchinskaya | URS | 11T. | 37.75 | 39.00 | 76.75 |

| 4T. Petrik | URS | 2T. | 38.35 | 38.35 | 76.70 |

| 4T. Zuchold | GDR | 5 | 38.20 | 38.50 | 76.70 |

| 6. Janz | GDR | 4 | 38.25 | 38.30 | 76.55 |

| 7T. Řimnáčová | TCH | 6 | 38.00 | 38.00 | 76.00 |

| 7T. Karaseva | URS | 7T. | 37.85 | 38.15 | 76.00 |

| 9T. Skleničková | TCH | 7T. | 37.85 | 38.00 | 75.85 |

| 9T. Krajčírová | TCH | 19 | 37.55 | 38.30 | 75.85 |

| 11. Lišková | TCH | 9T. | 37.80 | 37.85 | 75.65 |

| 12. Bauerschmidt | GDR | 15 | 37.65 | 37.80 | 75.45 |

| 13. Hanyu | JPN | 21 | 37.50 | 37.80 | 75.30 |

| 14. Bánfai | HUN | 19T | 37.55 | 37.55 | 75.10 |

| 15. Kubičková | TCH | 25T | 37.25 | 37.80 | 75.05 |

| 16. Rigby | USA | 18 | 37.60 | 37.35 | 74.95 |

| 17. Matsuhisa | JPN | 28 | 37.10 | 37.80 | 74.90 |

| 18. Nakamura-Mitsukuri | JPN | 11T. | 37.75 | 37.10 | 74.85 |

| 19T. Letourneur | FRA | 14 | 37.70 | 37.10 | 74.80 |

| 19T. Ducza-Jánosi | HUN | 15T. | 37.65 | 37.15 | 74.80 |

| 19T. Oda | JPN | 24 | 37.35 | 37.45 | 74.80 |

There was a lot of movement in the standings. Most notably, Kuchinskaya moved from 11th after compulsories to 3rd.

But we shouldn’t ignore Krajčírová, who was in 19th after compulsories and finished in 9th, and Kubičková, who was in 25th and finished 15th. The compulsory bar routine had gotten the best of both the aforementioned Czechoslovak gymnasts.

Watch Čáslavská relive her all-around gold medal.

From Věra ’68. All her emotions!

Judging Assignments

Here’s the work plan for the 1968 optionals competition. Keep in mind that these are the judges who were scheduled, but the working plan could change at the venue.

Vault

Superior Judge: Andreina Gotta (ITA)

Éva Romák (HUN)

Anette Stapleton (GBR)

Carin Delden (SWE)

Sylvia Hlaváček (GDR)

Uneven Bars

Superior Judge: Käthe Wiesenberger (AUT)

Irma Walther (GDR)

Radka Pentscheva (BUL)

Hana Vláčilova (TCH)

Maria Medveczky (CAN)

Balance Beam

Superior Judge: Valerie Nagy-Herpich (HUN)

Larisa Latynina (URS)

Jackie Uphues (USA)

Janina Skirlińska (POL)

Ingeborg Hermann (GDR)

Floor Exercise

Superior Judge: Taissia Demidenko (URS)

Michèle Thiébault (FRA)

Anna Anikina (URS)

Teresa Oliva (CUB)

Yoshida Natsu (JPN)

Note #1: You may recognize Anna Anikina’s name because she was one of Olga Mostepanova’s coaches.

Note #2: I already commented on some of the conflicts of interest in the post about the 1968 compuslories.

(Thanks to Hardy Fink for providing the assignments.)

A Few Skills Competed

Dale Flansaas of the United States documented some of the more exciting skills in the November/December issue of Mademoiselle Gymnast. We’ll look at the video footage from the 1968 event finals in the next post, but there are some skills that won’t appear in the footage.

Bars

The Burda twirl: “One of the Russian girls did a sole circle 1½ twist on the high bar recatching the high bar which was probably the most current new stunt thrown in the competition.”

- “Colleen Mulvihill used a front flip over the low bar from a front support to a recatch on the high bar”

- Colleen Mulvihill: “A free hip, ½ turn on high bar to an immediate double knee circle on the low bar”

- “Joyce Tanac uses a straddle vault to a bounce off closed legs on the high bar to an immediate back Somi.”

You can see the Tanac flip or the slapback dismount below. (Video from 1969)

Beam

Here are some of the skills that Flansaas recalls:

- Back handsprings

- Diving cartwheels

- Cartwheel immediate back handspring (not used in competition)

- 1-arm walkovers

- Handspring walkout to an immediate aerial dismount (Zuchold)

- A front aerial with a full twist dismount

- A back handspring to a chest roll down

The last bullet point should make you stop and wonder, “Wait, someone did that skill before Korbut?” Apparently so. Unfortunately, the gymnast’s name was not recorded by Flansaas.

Competition Notes

The Saga of Věra Čáslavská’s Beam Score

Here are the basics:

- During the optionals competition (IB), Čáslavská received a 9.65 for her beam routine.

- The crowd protested for over 10 minutes.

- Villancher, who was the president of the Women’s Technical Committee, interceded.

- Her beam score was raised to a 9.80.

- Since Čáslavská won by 1.4 points, the score change didn’t impact the final all-around results.

To get into the nitty-gritty on this subject, head over to this post.

Zuchold: The rightful bronze medalist?

Kuchinskaya was able to bounce back from 11th place in order to win the all-around bronze. Some felt that she received gift scores, which knocked Zuchold (and Petrik) down to fourth place by 0.05. Nick Stuart, the coach of the British men’s team, remarked:

This was an extraordinary case in Mexico. I think the crowd has conducted the marking to a considerable degree. Kuchinskaya was lucky. She was overmarked on her floor exercises. Caslavska received a similar gift on the beam, this was not so big a mistake in the overall context. But in fact, it worked itself out. I feel sorry for Zuchold of East Germany. She rated the bronze in my opinion.

The Times, Oct. 25, 1958

Nick Stuart wasn’t the only person who thought Kuchinskaya was overscored. A Japanese newspaper filed a similar report:

The crowd whistled and stomped its disapproval when Meyjid [sic] Kuchinskaya was credited with a 9.85 score in her floor exercise performance. A perfect score is 10 points and the crowd made it plain it felt the Russian girl was vastly overrewarded. But the score wasn’t changed.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 25, 1968

Čáslavská: Overscored because of the Crowd?

As Nick Stuart noted above, the crowd was guiding the scores. Some felt that this extended to Čáslavská, as well:

In general, the public, which in gymnastics should be extremely prepared, not only with regard to the aesthetics of the sport but also the degree of difficulty of the routines, was scandalous and annoying. They damaged the spectacle with inadequate protests and clearly favored Vera, who, being the best gymnast of the Games, saw her triumph tarnished with high scores where she was barely good.

El público por lo general, que en la gimnasia debería ser de lo más preparado, no solamente en lo que respeta a la estética del deporte sino al grado de dificultad de las rutinas, fue de lo más escandaloso y molesto, perjudicando al espectáculo con protestas inadecuadas y tomando claro partido a favor de Vera, que siendo la mejor gimnasta de los Juegos, vio empañado su triunfo con puntuajes altos donde apenas estuvo bien.

El Informador, October 27, 1968

My thought bubble: I am of two minds. On the one hand, the judges shouldn’t kowtow to the spectators — if the judges are doing their jobs. On the other hand, were the spectators’ boos and hisses a way of stopping cheating and score fixing?

Japan’s Fall from the Podium

In 1964, the Japanese women’s team had finished third. Coming into the competition, the Japanese media didn’t expect Japan’s women’s team to contend for a gold medal:

In the women gymnastics, Japan has no gold medal hopes in competing against the top-ranking gymnasts from the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia.

The Yomiuri, Sept. 28, 1968

However, when the team finished off the podium, there was overt disappointment in the Japanese press:

Japan, with a disappointing performance today failed to defend its 1964 Olympic bronze medal, and wound up in fourth place in team competition.

The Japanese girls compiled 375.45 points — 187.10 for the compulsory exercises Monday and 188.35 for the optional exercises today.

Little Kazue Hanyu, 17-year-old high school co-ed from Fukui, competing in her first international meet, was Japan’s top performer. She collected 37.50 points in the compulsory exercises and 37.80 in the free exercises for an overall total of 75.30. But it was not enough to place her among the top 10 world lady gymnast finalists.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 25, 1968

I wrote a post about the training conditions for Hanyu Kazue here.

Head Coach Latynina: Elated for Team Gold

But mixed feelings about Kuchinskaya.

Away from the podium stood the champion of the last three Olympiads, now the coach of the USSR national team. She was happy for her wonderful girls, rejoicing at her first victory in a new sports role.

L. LATYNINA, Honored Master of Sports:

– I’m happy for our glorious girls, who not only won with mastery, but also won over the hospitable Olympic hosts with charm.

Of course, the victory would have been more complete if we were first in the individual all-around. The failure of Natasha Kuchinskaya on the uneven bars practically deprived her of the opportunity to fight for the championship in the all-around, and she was ready for this. But even in spite of the disappointing failure, Natasha was able to take an honorable third place after the Czechoslovak athlete Věra Čáslavská and our Zina Voronina.

В стороне от пьедестала почета стояла чемпионка трех последних олимпиад, ныне тренер сборной СССР, и радовалась за своих замечательных девчат, радовалась своей первой победе в новом спортивном амплуа.

Л. ЛАТЫНИНА, заслуженный мастер спорта:

— я счастлива за наших славных девушек, которые покорили не только мастерством, но и обаянием гостеприимных хозяев Олимпиады.

Конечно, победа была бы более полной, если бы и в личных состязаниях мы были первыми. Неудача Наташи Кучинской на брусьях практически лишила ее возможности бороться за первенство в многоборье, а она была к этому готова. Но даже, несмотря на досадный срыв. Наташа смогла занять почетное третье место вслед за чехословацкой спортсменкой Верой Чаславской и нашей Зиной Ворониной.

Izvestiia, Oct. 24, 1968

Thanks to Nico for his help with the translation.

Tension and Questionable Etiquette on the Team Podium

Gymnastics fans have heard of Čáslavská’s protests on the podium during event finals. What has been forgotten is that the tension started on the team podium. Here’s what was reported at the time:

By the way, the contact between the Russian and Czech girls did not go as it should in sports.

Het contact tussen de Russische en de Tsjechische meisjes verliep trouwens niet zoals het in de sport behoort.

De Tijd , Oct. 24, 1968

The Mexican newspaper El Informador offered more details, highlighting a complete lack of interaction between the Soviet and Czechoslovak gymnasts:

During the team awards ceremony, the Soviet gymnasts did not exchange a single word with the Czech gymnasts, nor did they offer a handshake. On the contrary, they conversed happily with the East German gymnasts, the winners of the bronze medal.

The Czechoslovak gymnasts held a firm stance on the Olympic podium, looking straight forward, while the Soviet national anthem played. When the music finished, they kept their rigid stance to the acclamations of the spectators, while the Soviet gymnasts and German gymnasts waved to the public.

Durante la entrega de las medallas por equipos, las gimnastas soviéticas no intercambiaron ni una palabra ni estrecharon la mano a las gimnastas checas. Al contrario, conversaron alegremente con las alemanas del este, ganadoras de la medalla de bronce.

Las checoslovacas se mantuvieron en posición de firmes en el Podio Olímpico, mirando al frente, mientras sonaban las notas del himno soviéitco. Al terminar la música, asistieron también en rígida posición a las aclamaciones de los espectadores, mientras soviéticas y [alemanas] saludaban al público.

El Informador, Oct. 24, 1968

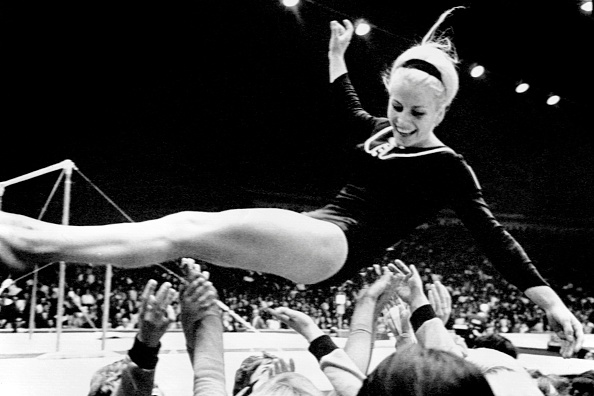

And you can see the contrast of the teams’ reactions in this photo:

Čáslavská’s Wedding Announcement

After the optionals competition, Čáslavská announced that she and Josef Odložil would marry in Mexico City on October 28. The couple had discussed this prior to the competition: If she repeated as the all-around champion, they would get married in Mexico. She also announced that she would retire from gymnastics.

Met haar overwinning op de achtkamp heeft de 26-jarig Vera Caslavska het „Ja-woord” bespoedigd aan haar landgenoot Jozef Odlozil, want Vera had zich voorgenomen in Mexico-city te trouwen, indien zij de gouden medaille zou halen.

Vera behaalde op de achtkamp in totaal 78.25 punten. Haar naaste concurrenten, de Russinnen Sinaida Voronina en Natalla Kutsinskaja konden dat puntentotaal met respectievelijk 76,85 en 78.75 niet eens benaderen.

Vera heeft met deze mooie overwinning haar carrière afgesloten. Zij is van plan na haar huwelijk op 28 oktober in Mexico-city met turnen te stoppen.

De Tijd, Oct. 24, 1968

The Times of London shared similar details about her retirement:

The East Germans could soon be passing the Czechs as Miss Caslavska announced that this is to be her last Olympics. She wants to marry and have children.

My thought bubble: Though it may have been unintentional, you have to smile at the juxtaposition. Kuchinskaya was known as “The Bride of Mexico” (“La novia de México”) in the Mexican press during the Olympics. Meanwhile, Čáslavská became a literal bride in Mexico.

Interesting enough, when Čáslavská passed away, the obituaries rewrote history, calling her “La novia de México” instead of Kuchinskaya.

The wedding was quite the spectacle. It was worldwide news. You can see scenes from this snippet of Věra ‘68.

Team Canada improved upon its rankings from the World Championships.

The Canadian girls placed 11th as a team, meaning that we jumped up four places from our 15th place at the World Games. Besides that, our top girl was Jennifer Diachun, Toronto, who was 51st all-around, (total 70.45). I was 62nd (total 69.75). My highest scoring event was balance beam (40th place). However, I felt my best events I had ever done, were floor exercise and vaulting.

Sandra Hartley, Modern Gymnast, March 1969

Team Canada continued to have problems finding a pianist.

It was an ongoing saga in the 1960s. In 1962, Poland’s pianist saved the day. In 1966, Bulgaria’s pianist saved the day. In 1968, Bulgaria’s pianist would again save the day.

A second handicap was the lack of a pianist. Seven days before the competition, we found out that our pianist was unable to come. We had been waiting two weeks for her arrival and had been practicing very little floor exercise because we had no music. The tape recorder would not work in Mexico. Finally, we were forced to work without music anyway. Not having a pianist was extremely damaging to my spirit especially. Music means everything to my work, and consequently, it was like working with a dislocated arm, from which I was already recovering. The Bulgarian pianist hastily learned our music, and played for us in the competition. He was a talented pianist, but under the circumstances, he had to cover up a lot on the spot.

Sandra Hartley, Modern Gymnast, March 1969

Amateurism, as required by the IOC, was becoming difficult for Canadian gymnasts.

In fact, in Sandra Hartley’s opinion, some countries had professional gymnasts.

Thirdly, I feel that we needed a training camp immediately prior to leaving for Mexico. The U.S.A. team trained at Lake Tahoe for three to four weeks prior to leaving, and had become extremely unified at that time. It was difficult for us to feel trained to maximum, as we were living in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. School, of course, made this an impossibility. The only alternative would have been to drop school for one year. This, another problem. To be a devoted gymnast, one must forsake work, school, social activity, and family life. As Canadians, we are brought up to maintain these very things. In other countries, athletes seem to have less trouble maintaining a livelihood on their own, and in this sense could be considered professional. Thus you may look at it this way — Canadian amateurs are competing against professionals. You can see why this would make winning for our country difficult.

Sandy Hartley, Modern Gymnast, March 1969

Note: “To be a devoted gymnast, one must forsake work, school, social activity, and family life.” This attitude existed in the 1960s already.

Amateurism was a big topic at the 1968 Olympics.

The Romanian press was also questioning amateurism at this Olympics.

As Új Élet, a Hungarian-language journal from Romania, noted,

Even the strictest rules [of amateurism] have been circumvented, and today the situation is that the concept of amateurism has expanded so much that, with the exception of certain sports, almost every competitor can fit.

A legszigorúbb szabályokat is kijátszották, s ma az a helyzet, hogy az amatőrség fogalma annyira kitágult, hogy egyes sportágaktól eltekintve, szinte minden versenyz belefér.

Új Élet, 19, Oct. 10, 1968

The article also alludes to capitalism’s culpability in expanding the definition of amateurism:

Initially, sports were amateur even without amateur regulations. It was played for pleasure and entertainment, but when the competitions spread, the capitalists noticed that “you can do business here,” and they did it.

A sport kezdetben amatőr-szbályzat nélkül is amatőr volt, kedvtelésből, szórakozásból űzték, a versenyek terjedésével egyidejűleg azonban a tőkések észrevették, hogy “itt üzletet lehet csinálni” s csináltak is.

Új Élet, 19, Oct. 10, 1968

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

Up next: The drama continues during the women’s event finals at the 1968 Olympics.

Spoiler alert: The majority of the event finals were debated.

More on 1968

3 replies on “1968: The Women’s Optionals Competition in Mexico City”

Antirussian, anti soviet article! The Russians were the best! Caslavska was really overscored. She was never very clean and was such an opportunistic person! She benefited from the political situation, which was terrible, but the Soviet gymnasts were not to blame. Petrik really deserved her gold medal. Such elegance and artistry!

If you can find articles from the late 1960s that make this argument, I’d be happy to include them in this post.

Kuchinskaya should not have even been on the all around podium – and it’s not because she fell in compulsories. She did make a big comeback – but she should have 6th at best. The floor routine used to be on YouTube and at 9.85 it is grossly overscored – as she stumbled out of her 2nd pass a full twist, then she left out the layout-stepout on the last pass so she only did a RO-FF for that pass. Anyone else on another team would have been ripped apart. At best it should have been a generous 9.5 or even more generous at 9.6. But it was 9.85 to ensure she made the podium and eked ahead of Zuchold/Petrik. So – she should NOT have been in the floor final either – and bronze there should rightfully be Voronina, who was underscored in team and event final in floor.