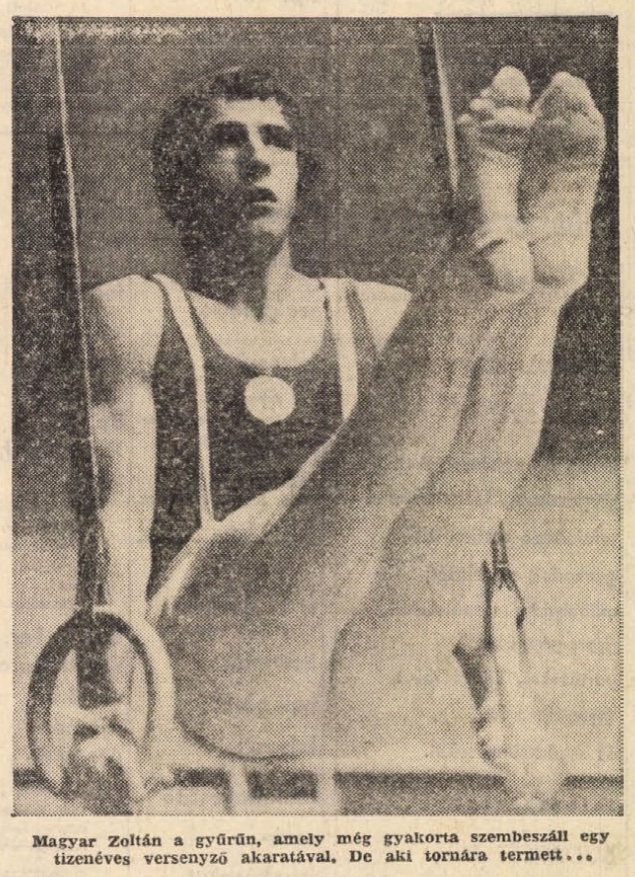

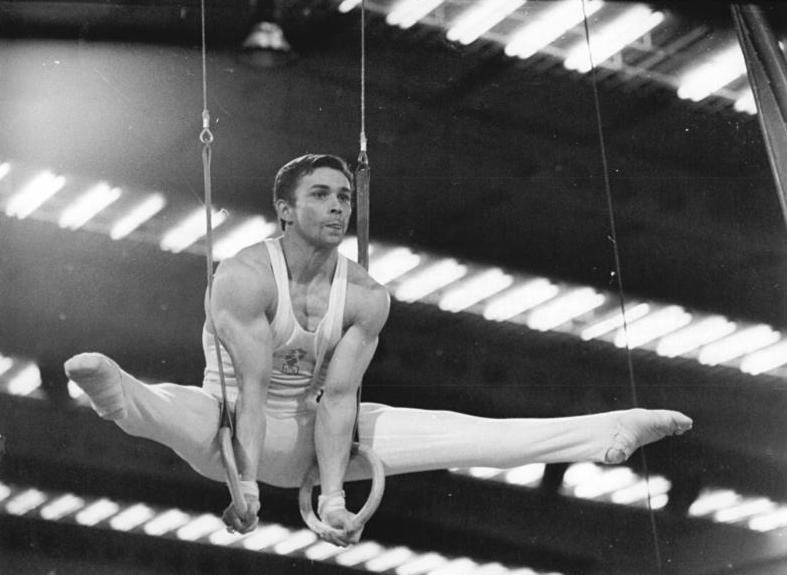

After the 1972 Olympics, the Hungarian sports newspaper Népsport ran a profile of Zoltán Magyar. It portrays the teenager as an angsty and absent-minded gymnast who sometimes forgets to show up for practice. But it recognizes that Magyar had the potential to become one of the best pommel workers in the world.

Note: For those who don’t know much about pommel horse, Magyar was known for his ability to travel down the pommel horse while touching the saddle of the horse (the leather part between the pommels). It’s challenging to use this part of the horse because you have to lift your legs above the pommel in the front and above the pommel in the back.

So, with no further ado, here’s the profile on Magyar.