After the 1972 Olympics, the Hungarian sports newspaper Népsport ran a profile of Zoltán Magyar. It portrays the teenager as an angsty and absent-minded gymnast who sometimes forgets to show up for practice. But it recognizes that Magyar had the potential to become one of the best pommel workers in the world.

Note: For those who don’t know much about pommel horse, Magyar was known for his ability to travel down the pommel horse while touching the saddle of the horse (the leather part between the pommels). It’s challenging to use this part of the horse because you have to lift your legs above the pommel in the front and above the pommel in the back.

So, with no further ado, here’s the profile on Magyar.

The Business Card of a Teenager

When, during the end of preparations for the Olympics, we approached the Hungarian experts to find out what we could expect from the male gymnasts, they were a bit secretive, and all that said was this: there is hope that one of our competitors will get into the finals. Two people had the chance for this: Imre Molnár, our best gymnast, and Zoltán Magyar. Whoever thought it was the former thought about his versatility, while whoever thought it to be the latter still remembered the international expectations, and the Romanian-Hungarian-Swiss competitions held in Bucharest during the summer, where the Swiss newspaper said the following: “Magyar Zoltán has a big chance to become a world-class sportsman on the pommel horse.”

At the Olympics in Munich, we found out that he indeed has the chance to become one.

Strange Hopes

[Context: In Munich, Magyar scored a 9.05 during compulsories, a 9.05 during the optionals, and a 9.50 during the all-around final. The article incorrectly listed Magyar’s pommel horse score as a 9.55 during the all-around finals.]

The big questions in August at home were the following: how well can a teenage gymnast handle the stress of the biggest competition there is? Is he mature enough to show his best performance when millions are watching, when he already showed at a smaller-scale competition that his muscle movement is not yet perfect? Magyar Zoltán proved a lot of things: With his 18 years, he finished 26th in the individual all-around competition. And if he would have not messed up the compulsory pommel horse routine and if he would have completed his optional routine during the team competition as he did in the individual all-around part — his score was [9.50] —, then there would have been hope that, in the finals, we could have cheered for a Hungarian competitor as well. Responsibility has a crushing weight, but this weight was not put on him by the Hungarian experts. They never told him what they were expecting from him. This hasty statement was published in a West German gymnastics newspaper in this form: “Only one gold medal may be taken from the Japanese, the one for the pommel horse and our number one candidate for this is Zoltán Magyar.” The Olympic village was not big enough to keep something like this a secret. And the “young rider” could not bear the weight of these hopes on his shoulders.

He did not get crushed by this. But his head kept spinning. After their return, they started working with him again, they are improving his exercises, and they are slowly leading him to the path where he can stand with more confidence and move forward. Ultimately it is because of his talent and the international interest in him that he, along with Imre Molnár, was invited to the Sihltal Cup in Switzerland. They are going there on Friday morning.

Take the Reins!

Zoltán Magyar is not a competitor yet and he is not an easy man to be around. But in the fiery mood that characterizes the world of gymnastics, the ones, who know him and also know that he has the talent try to — and not without results — take the reins. Let’s look at a few scenes to present his personality.

He does an incredible dismount off the high bar. His leg gets stuck between two mats. He wails. He does not want to continue. The next day he is asking to have his requirements lightened, yet he does a perfect double twist off the rings. He is complaining. His coach, László Vigh asks him during his shower: “Does your leg hurt still?” He answers with a big grin: “It didn’t really hurt in the first place.”

He is on the bar. “Why aren’t you pointing your toes, Zoli?” — says head coach, István Sárkány. “Because my palm hurts!” — he answers. Well, this is what it is like with a teenage gymnast, who is still struggling with his temper…

But if somebody was born to be a gymnast, it is hard to get out. In the beginning József Harmath, the head coach of the FTC, had to bring him back twice until he finally stayed there. Now he only needs to be reminded of the fact that he is a gymnast when he forgets about the practices from time to time… Even though there are eight practices a week!

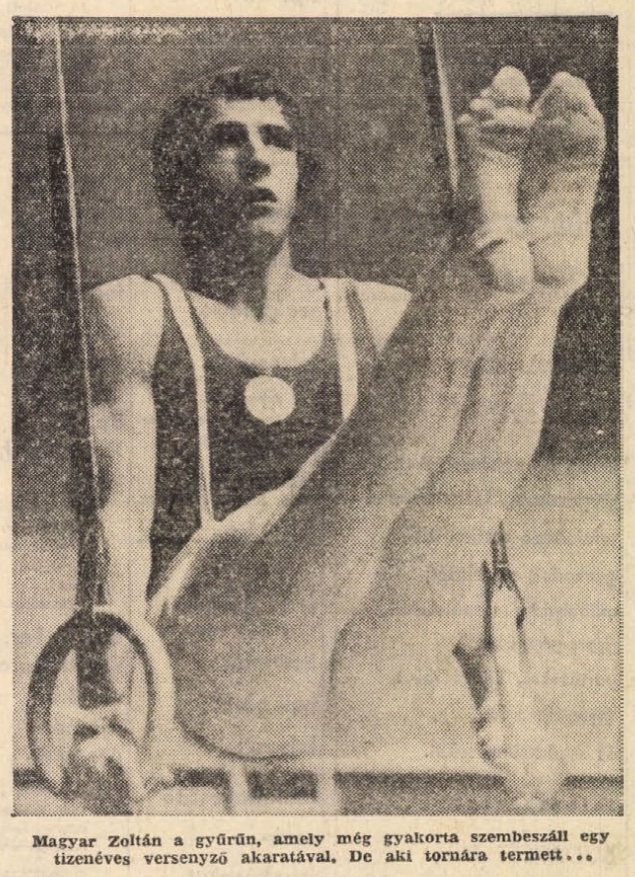

He is a versatile gymnast, there is nothing he is bad at, he can’t do a proper iron cross on the rings, but he is always ready to amaze. He can do a double twist on floor, he dismounts from rings with a double salto, when he vaults, he can do a handspring salto, on parallel bars, he can do two back tosses to handstand, on the bar, he does an underswing into a front salto, on the pommel horse… He not only ‘rides’ all sides of the horse — but this is something only he can do — but the middle part as well!

— It was hard to make him try to do this new idea — László Vigh thinks back to these “heroic times” while sighing. — In the beginning, we put a mat between the two sides, maybe the 12 cm hole seems less scary like that. We practiced a lot on the floor as well, where we drew a horse. Then we went back on the equipment — with a prickly doormat… I happened to find one just like that… It hurt Zoli’s hand very much, he threw it out and he has been doing without it ever since…

The Journey Continues

This is how the exercise, which incorporates the hardest elements and which grabbed the whole world’s attention, was born.

An almost 19-year-old is still living out his teenage rage. He is not ready to be reined in, but he slowly seems to realize that he is at the beginning of his journey, and in Munich he only showed his name card. His first real Olympics will be in Montreal…

If he wants it as well.

Népsport, November 30, 1972

Egy tizenéves névjegye

Amikor az olimpiai előkészületek hajrájában szólásra kértük a magyar szakembereket azzal a céllal, hogy mit is várhatunk férfi tornászainktól, némileg titokzatosságba burkolózva jelentették ki: remény van arra, hogy valamelyik versenyzőnk bekerül a szerenkénti döntőbe. Két esélyes lehetett erre a megtisztelő szerepre: Molnár Imre, első számú tornászunk és Magyar Zoltán. Aki az előbbire gondolt, sokoldalúságából indult ki, aki az utóbbira, annak még fülében csengtek a nemzetközi várakozás hangjai, s köztük is a nyári, bukaresti román—magyar—svájci verseny, amely után a svájci tornaszaklap így cikkezett: „Lólengésben Magyar Zoltán személyében nemzetközi klasszis van születőben.”

Ahogy azután a müncheni olimpia bizonyította: valóban születőben van.

Idegen remények

Az augusztus eleji kérdőjeleket így fogalmazták itthon: vajon egy tizenéves tornász menynyire tudja lelkileg-idegileg elviselni a versenyek legnagyobbikának terhét? Megérett-e már arra, hogy milliók figyelő szeme előtt a legjobbat nyújtsa, amikor kisebb jelentőségű versenyen is bizonyította, hogy a mozgásbeidegződés még nem tökéletes? Magyar Zoltán sok mindent igazolt odakint: 18 éves fejjel a 26. helyen végzett az egyéni összetettben. S ha nem rontja el lólengésben a kötelezőket, s úgy teljesíti híressé vált szabadprogramját a csapatversenyben is, ahogy az egyéni öszszetett során — [9.50]-öt kapott rá —, akkor megalapozott lett volna a remény, hogy a szerenkénti döntőben magyar versenyzőnek is szurkolhattunk volna. A felelősség nyomasztó súly, de ezt a terhet nem a magyar szakemberek rakták a vállára. Ők gondosan titkolták előle azt, hogy mit várnak tőle. A meggondolatlan kijelentés a nyugatnémet tornaszaklapban látott napvilágot, olyan megjegyzés formájában, miszerint „A japánoktól egyetlen aranyérmet lehet elvenni, mégpedig lólengésben, s erre az első számú jelölt Magyar Zoltán.” Az olimpiai falu nem volt eléggé nagy ahhoz, hogy az ilyesmit el lehessen titkolni. S „a kis lovas” valósággal meggörnyedt a rázúduló remények súlya alatt.

Nem roppant össze — szó sincs ilyesmiről! Csak éppenséggel kóválygott kissé. Hazatérve újra megfogták a kezét, erősítik gyakorlatanyagát, s rávezetik fokról fokra arra az útra, amelyen lassan mind magabiztosabban áll majd és halad tovább. Végeredményben tehetségének és az iránta tanúsított nemzetközi érdeklődésnek szól az is, hogy Molnár Imrével emiatt meghívták Svájcba, a Sihltal Kupára, ahova pénteken reggel indulnak.

Gyeplőt a kézbe!

Magyar Zoltán nem kész versenyző és nem könnyű ember. De a tornaszerek izzó hangulatú világában igyekeznek — s nem is eredménytelenül — kézben tartani a gyeplőt fickándozásai közben azok, akik ismerik és tudják, hogy sok, nagyon sok van benne. Villantsunk fel néhány képet, hogy megvilágítsuk egyéniséget.

Csinál egy ragyogó nyújtóleugrást. Két szőnyeg közé szorul a lába. Jajgat. Felmentést kér a folytatás alól. Másnap is könnyítésért esedezik, de közben tökéletes duplacsavarral jön le a gyűrűről. Zsörtölődik. Zuhanyozás közben megkérdezi tőle edzője, Vigh László: „Fáj még a lábad?” Kamaszos vigyor közepette érkezik a válasz: „Á, nem is fájt olyan nagyon!”

A nyújtón dolgozik. „Miért nem feszíted a lábfejed, Zoli?” — csattan Sárkány István vezetőedző hangja. „Mert sajog a tenyerem!” — felel készségesen. Hát ilyen egy tinédzser tornász, aki a fiatalkor vadhajtásaival küszködik…

Ha azonban valaki tornára termett, nehezen tud megszökni előle. Úgy kezdődött ugyanis, hogy Harmath József, az FTC vezetőedzője, aki felfedezte, kétszer hozta vissza a terembe, amíg megragadt. Most már csak olyankor kell emlékezetébe idézni, hogy ő tornász, ha időnkint elfelejtkezik az edzésekről … Pedig hetenkint nyolc is van belőle!

Sokoldalú tornász, nincs „lyukas” szere, bár gyűrűn nem képes ma még végrehajtani a szabályos keresztfüggést, de bravúrra mindig készen áll! Talajon tudja a duplacsavart, a gyűrűről duplaszaltóval érkezik le, ugrásban másfélszaltót csinál, korláton duplaléghengerből kézállást, nyújtón nyílugrásból bicskaszaltót előre, lovon pedig… Nem pusztán a ló minden oldalát „lovagolja meg”, hanem — egyedülállóan a világon — a kápa közötti részt is!

— Nehezen lehetett rávenni, hogy megpróbálja megvalósítani ezt az új elképzelést — emlékszik a „hősi időkre” nagy sóhaj kíséretében Vigh László. — Úgy kezdtük, hogy a két nyeregkápa közé lábtörlőt tettünk be, hátha így nem hat olyan félelmetesnek a 12 centis mélyedés. Sokat gyakoroltunk a földön is, ahová lerajzoltuk a lovat. Azután visszamentünk a szerre — szúrós lábtörlővel… Úgy adódott, hogy egy olyan akadt a kezembe… Sértette kegyetlenül a Zoli kezét, kivágta a lóról és azóta anélkül csinálja .. „

Az út folytatása

Így született az a gyakorlat, amely zsúfolja a legnehezebb elemeket, s amelyre felfigyelt a vili.

Egy 19. évéhez közeledő fiatalember forrongó korszakát éli. Tépi meg a fegyelem zablását, de alakul benne a hónapokkal párhuzamosan az a tudat is, hogy még csak az út elején áll, s Münchenben pusztán a névjegyét adta le. Az ő első igazi olimpiája , Montreal lesz …

Ha ő is úgy akarja.

Note: After the 1972 Olympics, Magyar would go on to win almost every major pommel horse title during the 1970s:

- 1973 European Championships

- 1974 World Championships

- 1975 European Championships

- 1976 Olympic Games

- 1977 European Championships

- 1978 World Championships

- 1979 World Championships

- 1980 Olympic Games

More on 1972