In 1972, the Hungarian team won bronze at the Olympics, yet little has been written about the team’s gymnasts in the English language. To give some personality to the names in the record books, I’ve translated newspaper profiles of three gymnasts: Ilona Békesi, Krisztina Medveczky, and Monika Császár.

Ilona Békési was indisputably the top gymnast on the team. At the 1971 Hungarian Nationals, she swept every event, and as you’ll see, she was often portrayed as a tenacious gymnast with great willpower. Krisztina Medveczky was depicted as the young, wide-eyed teammate who was only 14 when she made the team. And Monika Császár was a humble gymnast who did not enjoy the spotlight.

Ilona Békési

Note: Newspapers today would probably avoid the title below.

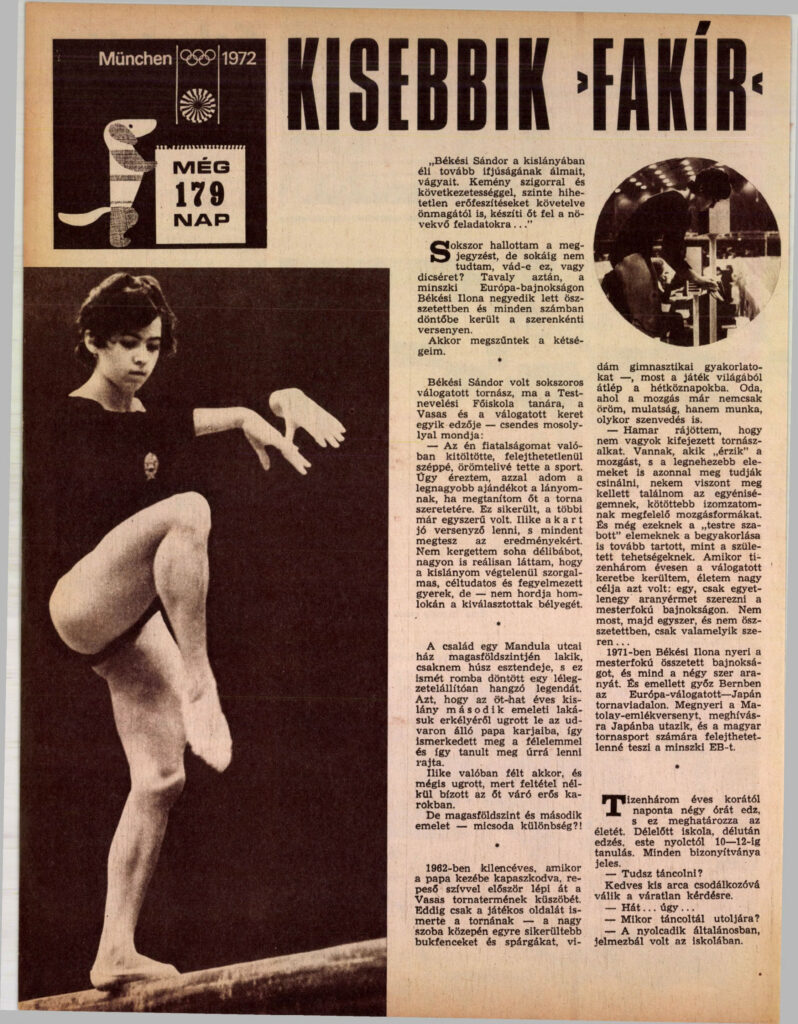

The Younger Fakir

“Sándor Békési’s dreams from his youth live on in his little daughter. He is preparing her for the ever-growing tasks with full stringency and consistency, which require almost unbelievable effort from him as well…”

I heard this comment a lot, but I never knew whether it was meant as an accusation or praise. Then last year Ilona Békési achieved fourth place at the European Championship in Minsk in the all-around competition and she managed to get into the finals in all events.

Then all my doubts were resolved.

Sándor Békési, a former national team gymnast many times, today a teacher at the University of Physical Education, one of the coaches for Vasas and the national team — says with a quiet smile:

— Sport made my youth complete, it made it unbelievably beautiful and joyful. I thought that the biggest gift I could give my daughter is to teach her the love of gymnastics. I managed to do this; the rest was easy. Ilike was the one who wanted to start competing, and she does everything to achieve good results. I never had pipe dreams, I was very realistic when I determined that my daughter is an immensely diligent, determined, and disciplined child, but she does not act as if she were the chosen one.

*

The family has been living in Mandula street on the mezzanine floor for almost twenty years now, which debunks a legend that sounds really breathtaking. According to this legend, the five- or six-year-old daughter jumped from the balcony of their second-floor apartment to the arms of her father standing in the yard. This is how she was introduced to fear and this is how she learned to overcome it. Ilike was of course afraid then, but she jumped anyway because she trusted the strong arms waiting to catch her. But the mezzanine and the second floor — what a difference?!

[Note: The “magasföldszint” (mezzanine level) is above the normal height of the ground floor but lower than the height of the second floor.]

*

She was nine years old in 1962, when, with a joyfully beating heart, she entered the Vasas gym clinging to her father’s arm. Until then she only knew the fun part of gymnastics — she managed to do better and better flips and splits, all kinds of merry gymnastic moves in their living room — but now the sport became part of her everyday life. From now on, moving is no longer just fun and joy, but it also requires work and sometimes even suffering.

— I quickly discovered that I don’t have what you would call the typical gymnast physique. There are those, who simply “feel” the moves, they can immediately do even the harder elements. I, on the other hand, have to find the exercise that fits my personality and tighter muscles. And even these elements “tailored to my body” took more time to master than it does for those natural talents. When I made it to the national team at the age of thirteen, my goal in life was the following: just to win one, only one gold medal at the masters championships. Not now, but sometimes in the future, and not in the all-around rankings, but only in one event…

In 1971, Békési Ilona won the Master all-around championship and also won gold in all events. And the European team won in Bern at the Japanese gymnastics competition.

She won the Matolay Remembrance games, then she was invited to travel to Japan, and she made the European Championship in Minsk an unforgettable event for everyone in the world of Hungarian gymnastics.

*

She trains four hours a day since the age of thirteen and this defines her life. School in the morning, training in the afternoon, then studying from 8 pm until 10 pm or 12 am. She has straight A’s on her report cards.

— Can you dance? There is an amused look on her kind face upon hearing this unexpected question.

— Well… a bit…

— When did you dance the last time?

— When I was in eighth grade, there was a costume ball at school.

— What is your favorite dance?

— Please, don’t laugh… The waltz.

— Do you have a boyfriend?

— Me?! When would I find the time for boys?

— During the breaks between classes for example.

— I study then.

— Ilike! Aren’t you giving up too much for the sake of sports? She bows her head; it is hard for her to say what she wants. She doesn’t like to reveal too much about herself.

— I came back from the European Championship last year. Sometimes I still feel like it was just a dream and that I would wake up one day and realize that I never went to Minsk and I never achieved those unbelievable results…

•

Her mother has a nickname for her daughter and father, she calls them the “two fakirs.” They never get tired.

[Note: In Hungarian, one definition for fakír is to be over-demanding or self-denying.]

The younger “fakir” has a slight smile on her face while sitting in the low armchair, her two arms — from which the plaster was only taken off a few days ago — lay in her lap in a strangely unnatural pose.

— One gets used to the minor and major pain that goes together with gymnastics. The first time I ever had a strange and horrible feeling, that I could not compare to anything, was when I fell off the the upper bar of the uneven bars three weeks ago. I raised my head, I looked to my right side — I just saw how my elbow bounced back. I looked to my left side; I saw a huge “T” letter where my left elbow ought to be. The pain was nothing compared to the feeling I had. What if…

— … the injury is so severe that you can never do gymnastics again or you can’t go to the Olympics? Her face recoiled.

— Please, don’t say something like that! Now I know that this is where the real struggle begins…

•

Ilike now goes to physiotherapy, where they train her arms, and her father massages them at home. So now it’s time for some relaxation, music, and rest? Oh, no! It’s study time, because there is a class exam on the first of March, and then comes the graduation at the end of the month. And then nothing else is left, but the Olympics in Munich.

— What do the doctors say?

— Maybe in a month or even a bit sooner — I can start again.

— Aren’t you going to be afraid after such a severe injury?

— I just wish I could be on the bar again!

Képes Sport, February 29, 1972

Kisebbik Fakir

„Békési Sándor a kislányában éli tovább ifjúságának álmait, vágyait. Kemény szigorral és következetességgel, szinte hihetetlen erőfeszítéseket követelve önmagától is, készíti őt fel a növekvő feladatokra…”

Sokszor hallottam a megjegyzést, de sokáig nem tudtam, vád-e ez, vagy dicséret? Tavaly aztán, a minszki Európa-bajnokságon Békési Ilona negyedik lett öszszetettben és minden számban döntőbe került a szerenkénti versenyen.

Akkor megszűntek a kétségeim.

Békési Sándor volt sokszoros válogatott tornász, ma a Testnevelési Főiskola tanára, a Vasas és a válogatott keret egyik edzője — csendes mosolylyal mondja:

— Az én fiatalságomat valóban kitöltötte, felejthetetlenül széppé, örömtelivé tette a sport. Úgy éreztem, azzal adom a legnagyobb ajándékot a lányomnak, ha megtanítom őt a torna szeretetére. Ez sikerült, a többi már egyszerű volt. Ilike akart jó versenyző lenni, s mindent megtesz az eredményekért. Nem kergettem soha délibábot, nagyon is reálisan láttam, hogy a kislányom végtelenül szorgalmas, céltudatos és fegyelmezett gyerek, de nem hordja homlokán a kiválasztottak bélyegét.

*

A család egy Mandula utcai ház magasföldszintjén lakik, csaknem húsz esztendeje, s ez ismét romba döntött egy lélegzetelállítóan hangzó legendát. Azt, hogy az öt-hat éves kislány második emeleti lakásuk erkélyéről ugrott le az udvaron álló papa karjaiba, így ismerkedett meg a félelemmel és így tanult meg úrrá lenni rajta. Ilike valóban félt akkor, és mégis ugrott, mert feltétel nélkül bízott az őt váró erős karokban. De magasföldszint és második emelet — micsoda különbség?!

*

1962-ben kilencéves, amikor a papa kezébe kapaszkodva, repeső szívvel először lépi át a Vasas tornatermének küszöbét. Eddig csak a játékos oldalát ismerte a tornának — a nagy szoba közepén egyre sikerültebb bukfenceket és spárgákat, vidám gimnasztikai gyakorlatokat —, most a játék világából átlép a hétköznapokba. Oda, ahol a mozgás már nemcsak öröm, mulatság, hanem munka, olykor szenvedés is.

— Hamar rájöttem, hogy nem vagyok kifejezett tornászaikat. Vannak, akik „érzik” a mozgást, s a legnehezebb elemeket is azonnal meg tudják csinálni, nekem viszont meg kellett találnom az egyéniségemnek, kötöttebb izomzatomnak megfelelő mozgásformákat. És még ezeknek a „testre szabott” elemeknek a begyakorlása is tovább tartott, mint a született tehetségeknek. Amikor tizenhárom évesen a válogatott keretbe kerültem, életem nagy célja azt volt: egy, csak egyetlenegy aranyérmet szerezni a mesterfokú bajnokságon. Nem most, majd egyszer, és nem öszszetettben, csak valamelyik szeren …

1971-ben Békési Ilona nyeri a mesterfokú összetett bajnokságot, és mind a négy szer aranyát. És emellett győz Bernben az Európa-válogatott a Japán tornaviadalon. Megnyeri a Matolay-emlékversenyt, meghívásra Japánba utazik, és a magyar tornasport számára felejthetetlenné teszi a minszki EB-t.

*

Tizenhárom éves korától naponta négy órát edz, s ez meghatározza az életét. Délelőtt iskola, délután edzés, este nyolctól 10—12-ig tanulás. Minden bizonyítványa jeles. — Tudsz táncolni? Kedves kis arca csodálkozóvá válik a váratlan kérdésre. — Hát… úgy… — Mikor táncoltál utoljára? — A nyolcadik általánosban, jelmezbál volt az iskolában.

— Melyik táncot kedveled legjobban?

— Ne tessék kinevetni… A keringőt.

— Udvarlód van?

— Nekem?! De hát mikor érnék én rá fiúkkal foglalkozni?

— Például az óraszünetekben.

— Akkor tanulok.

— Ilike! Nem túl sok az, amiről lemondasz a sport kedvéért? Lehajtja a fejét, nehezen mondja ki, amit akar. Nem kitárulkozó természet.

— Tavaly, már hazajöttem az Európa-bajnokságról, néha még mindig úgy éreztem, álmodom, s egyszer csak felébredek és kiderül: nem is én voltam ott Minszkben és dehogyis értem el azokat az elérhetetlennek tűnő eredményeket…

•

A mami csak úgy „becézi” férjét és gyermekét, hogy „két fakír”. Nem fáradnak el soha.

A kisebbik „fakír” most apró mosollyal ül az alacsony fotelben, két karja — amelyekről a napokban vették le a gipszet — még mindig valami furcsán természetellenes pózban nehezedik az ölébe.

— A tornával együttjáró kisebb-nagyobb fájdalmakat könnyen megszokja az ember. Akkor éreztem először valami nehéz, semmihez sem hasonlítható szörnyű érzést, amikor három hete leestem a felemás felső karfájáról. Felemeltem a fejem, jobbra néztem — éppen akkor ugrott vissza a jobb könyököm. Balra néztem, a bal könyököm helyén egy óriásira nőtt „T” betűt láttam. A fájdalom semmi sem volt ahhoz az érzéshez képest, ami belém nyilatt. Mi lesz, ha …

— … ha olyan súlyos a sérülés, hogy nem tudsz többé tornászni, vagy nem mehetsz az olimpiára? Az arca megrándul.

— Ne is tessék ilyeneket mondani! Már tudom, itt kezdődik valahol az igazi szenvedés …

•

Ilike most fizikoterápiára jár, ahol tornásztatják a karjait, odahaza pedig az apa masszírozza. Hogy ilyenkor jöhet a kikapcsolódás, zene, pihenés ? Ó, nem! Jöhet a tanulás, mert március elsején osztályvizsga, s a hónap végén érettségi következik. És aztán már nem lesz más, csak München és olimpia.

— Mit mondanak az orvosok?

— Talán egy hónap múlva, esetleg már valamivel előbb is — újra kezdhetem.

— Nem fogsz félni ezután a súlyos sérülés után?

— Csak már újra megfoghatnám azt a korlátot!

Krisztina Medveczky

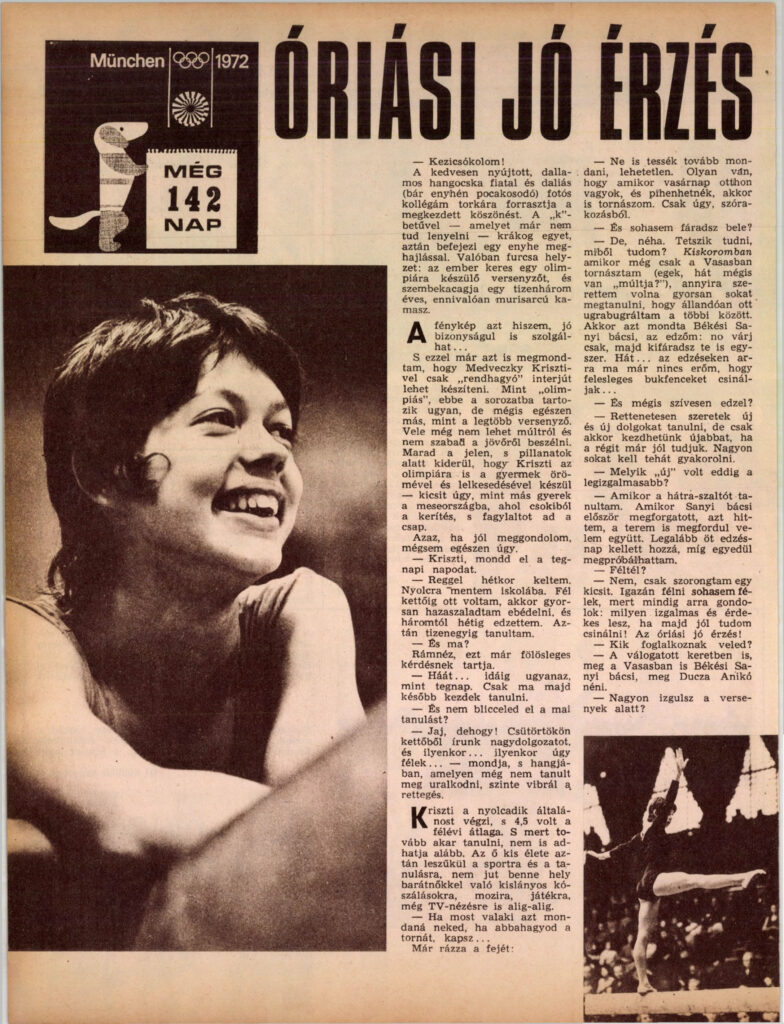

Such a Great Feeling

— Greetings!

The nicely extended, melodic voice leaves my young and charming (although his belly is starting to stick out) photographer colleague speechless. He croaks a letter “g” — as he can no longer withdraw it — and then he just bows a bit. It is a strange situation indeed: one looks for an Olympic contender and then there is this laughing thirteen-year-old teenager with her incredibly cute face.

[Note: This profile was printed shortly before her 14th birthday.]

The photo will testify to what I am saying…

And thus I already disclosed that you can only make an “irregular” interview with Kriszti Medveczky. She belongs to this series as “someone going to the Olympics,” yet she is something entirely different from the other contenders. You can’t talk to her about her past, but you are not allowed to mention the future. The present is what remains, after a second, we already find out that Kriszti is preparing for the Olympics with the joy and enthusiasm of a child — a bit like other kids would prepare for wonderland, where the fences are made of chocolate and ice cream flows from the faucets.

When I think about it, maybe it is not like that at all.

— Kriszti, tell me about your previous day.

— I got up at seven. I had to be at school at eight. I was there until half past one, then I ran home to have lunch and had training from three to seven o’clock. Then I studied until eleven.

— And today? She looks at me, and I see she finds this question unnecessary.

— Well… it was the same as yesterday until now. But I’ll start studying a bit later.

— Don’t you try to get out of studying?

— Oh, no! We’ll have two tests on Thursday, and at times like this I… I worry so much… — says she and in her voice, you can feel the fear vibrating as she has not yet learned to control it.

Kriszti is currently in the eighth grade, at the end of the previous semester her average was 4.5. She wants to continue school, so she can’t get lazy. Her little life comes down to sports and studying. There is no time to fool around with her girlfriends, go to the cinema, plays, she hardly has time for TV.

— If someone would tell you now that if you stop doing sports then you would get …

She is already shaking her head:

— Please, don’t even finish that, it is impossible. Sometimes when I am at home on Sundays and I could rest, I still train. Just for fun.

— And you never get tired of it?

— I do sometimes. Do you want to know how I know it? When I was younger and I was only training in Vasas (my god, so she has a “past” after all?) I wanted to learn a lot in a short time, so I was always jumping around among the others. Then, my coach, Sanyi Békési, told me: well, just wait, you’ll get tired once as well. Well… now I no longer have the energy to just jump around and do flips for no reason…

— Yet you like to train anyway?

— I very much like to learn new things, but we can only start new things once we learned the previous thing. I have to train a lot.

— What “new” thing was the most exciting so far?

— When I was learning how to do a backflip. When Sanyi turned me for the first time I thought the world would flip with me too. I needed at least five days until I could try it on my own.

— Were you afraid?

— No, I just felt a bit anxious. I am never really afraid because I always think of how exciting and interesting it will be when I learn to do it well. That’s such a great feeling! — Who are your trainers?

— Sanyi Békési and Anikó Ducza on the national team and in Vasas as well.

— Are you very excited because of the competitions?

— I don’t have time to be excited, I have to concentrate. I only think about what my trainers said: to keep my hips straight, my head up and… and, well as much as I can — she laughs at this — to make my arms and legs graceful.

Do you have a favorite?

— Tourischeva! She moves so nicely and she is really into what she is doing. She is not my role model, but many other gymnasts think the same of her, because she is nice and very humble.

— How do you know that? This was the first time you met her.

— Ilike told me how nice and friendly she was, like she hasn’t won multiple world and Olympic championships, like she was just like us. And I love and respect Ilike very much. Do you know that she graduated with straight A’s?

— What was your favorite sports event so far?

— The ORT in Katowice [Poland]. Before that we only cheered that someone would get into the finals, I never thought I could be that someone. The fact that I won third place on the beam was a really nice and good feeling.

— Did you ever come up with something for your routines?

— Nah, that’s Sanyi’s and Anikó’s task. But — she adds and her face already foretells her immediate cheerfulness — in the evening when I can’t sleep, I always come up with some ideas for my routines. They’re always so great, but usually they are so fantastical that they could not be performed. Not today at least…

— What do your parents think about you spending so much time doing sports?

— They like that I am doing sports because in their view nothing else would be such a great pastime for me. And now that it went the way it did… maybe they are even proud of me a bit.

— And you? Would you be very upset if you would not get to go to Munich?

— First of all, it is not at all certain that I will be going, as everyone on the national team is working just as hard as I do, and they want it just as much as I do. So, I don’t even think about this. I just do everything that my coaches tell me to. I still know so little about the sport. But one thing is for sure, it is up to me whether I will become a good gymnast or not, or…

And she shrugs her shoulders and lets me finish the sentence. She says goodbye, grabs her bags, and runs home to study. But I am not thinking about that “or” either. I am sure that Kriszti will become a good gymnast…

Képes Sport, April 4, 1972

ÓRIÁSI JÓ ÉRZES

— Kezicsókolom!

A kedvesen nyújtott, dallamos hangocska fiatal és daliás (bár enyhén pocakosodó) fotós kollégám torkára forrasztja a megkezdett köszönést. A „k”betűvel — amelyet már nem tud lenyelni — krákog egyet, aztán befejezi egy enyhe meghajlással. Valóban furcsa helyzet: az ember keres egy olimpiára készülő versenyzőt, és szembekacagja egy tizenhárom éves, ennivalóan murisarcú kamasz.

A fénykép azt hiszem, jó bizonyságul is szolgálhat …

S ezzel már azt is megmondtam, hogy Medveczky Krisztivel csak „rendhagyó” interjút lehet készíteni. Mint „olimpiás”, ebbe a sorozatba tartozik ugyan, de mégis egészen más, mint a legtöbb versenyző. Vele még nem lehet múltról és nem szabad a jövőről beszélni. Marad a jelen, s pillanatok alatt kiderül, hogy Kriszti az olimpiára is a gyermek örömével és lelkesedésével készül — kicsit úgy, mint más gyerek a meseországba, ahol csokiból a kerítés, s fagylaltot ad a csap.

Azaz, ha jól meggondolom, mégsem egészen úgy.

— Kriszti, mondd el a tegnapi napodat.

— Reggel hétkor keltem. Nyolcramentem iskolába. Fél kettőig ott voltam, akkor gyorsan hazaszaladtam ebédelni, és háromtól hétig edzettem. Aztán tizenegyig tanultam.

— És ma? Rám néz, ezt már fölösleges kérdésnek tartja.

— Háát… idáig ugyanaz, mint tegnap. Csak ma majd később kezdek tanulni.

— És nem blicceled el a mai tanulást?

— Jaj, dehogy! Csütörtökön kettőből írunk nagydolgozatot, és ilyenkor… ilyenkor úgy félek… — mondja, s hangjában, amelyen még nem tanult meg uralkodni, szinte vibrál a rettegés.

Kriszti a nyolcadik általánost végzi, s 4,5 volt a félévi átlaga. S mert tovább akar tanulni, nem is adhatja alább. Az ő kis élete aztán leszűkül a sportra és a tanulásra, nem jut benne hely barátnőkkel való kislányos kószálásokra, mozira, játékra, még TV-nézésre is alig-alig.

— Ha most valaki azt mondaná neked, ha abbahagyod a tornát, kapsz …

Már rázza a fejét:

— Ne is tessék tovább mondani, lehetetlen. Olyan van, hogy amikor vasárnap otthon vagyok, és pihenhetnék, akkor is tornászom. Csak úgy, szórakozásból.

— És sohasem fáradsz bele?

— De, néha. Tetszik tudni, miből tudom ? Kiskoromban amikor még csak a Vasasban tornásztam (egek, hát mégis van „múltja?”), annyira szerettem volna gyorsan sokat megtanulni, hogy állandóan ott ugrabugráltam a többi között. Akkor azt mondta Békési Sanyi bácsi, az edzőm: ne várj csak, majd kifáradsz te is egyszer. Hát… az edzéseken arra ma már nincs erőm, hogy felesleges bukfenceket csináljak …

— És mégis szívesen edzel?

— Rettenetesen szeretek új és új dolgokat tanulni, de csak akkor kezdhetünk újabbat, ha a régit már jól tudjuk. Nagyon sokat kell tehát gyakorolni.

— Melyik „új” volt eddig a legizgalmasabb?

— Amikor a hátraszaltót tanultam. Amikor Sanyi bácsi először megforgatott, azt hittem, a terem is megfordul velem együtt. Legalább öt edzésnap kellett hozzá, míg egyedül megpróbálhattam.

— Féltél?

— Nem, csak szorongtam egy kicsit. Igazán félni sohasem félek, mert mindig arra gondolok , milyen izgalmas és érdekes lesz, ha majd jól tudom csinálni! Az óriási jó érzés! — Kik foglalkoznak veled?

— A válogatott keretben is, meg a Vasasban is Békési Sanyi bácsi, meg Ducza Anikó néni.

— Nagyon izgulsz a versenyek alatt?

— Nem érek rá izgulni, mert nagyon kell összpontosítanom. Csak arra gondolok, amit az edzőim mondtak: hogy egyenesen tartsam a derekam, fel a fejemet és… hát, már amennyire én tudom — és ezen jót mulat — kecsesen a kezem meg a lábam.

Van kedvenced ?

— Turiscseva! Mert olyan nagyon szép a mozgása, s úgy átéli, amit csinál. Nemcsak nekem, még sok tornásznak ő a példaképe, mert kedves és nagyon-nagyon szerény.

— Honnan tudod, hiszen most találkoztál vele először?

— Az Ilike mesélte el, hogy milyen aranyos és közvetlen, mintha nem is többszörös világ- és olimpiai bajnok volna, csak olyan mint… mint mi. És nagyon szeretem és tisztelem Ilikét. Tetszik tudni, hogy jelesen érettségizett?

— Melyik az eddigi legkedvesebb sportélményed ?

— A katowicei ORT. Előtte csak azért szurkoltunk, hogy valaki bekerüljön közülünk a döntőbe, arra nem is gondoltam, hogy az én is lehetek. Aztán, hogy harmadik lettem gerendán, az nagyon szép és jó érzés volt.

— Találtál már ki te is valamit a gyakorlataidhoz?

— Áh, az Sanyi bácsi, meg Anikó néni dolga. De — teszi hozzá, s az arca előre kiabálja a hirtelen felgyűlő jókedvet — este, amikor nem tudok elaludni, mindig el-elgondolok magamnak egy gyakorlatot. Mindig nagyon jól néznek ki, de rendszerint olyan fantasztikusak, hogy nem lehetne őket megcsinálni. Ma még nem…

— Szüleid mit szólnak ahhoz, hogy ilyen sok időt vesz el tőled a sport?

— Örülnek hogy sportolok, mert úgy gondolják, hogy semmi más nem lenne ilyen hasznos időtöltés számomra. És, hogy most még így is sikerült … talán büszkék is egy kicsit.

— És te? Egyáltalán, nagyon el lennél keseredve, ha nem jutnál ki Münchenbe?

— Először, még egyáltalán nem biztos, hogy kijutok, hiszen a keretben mindenki épp oly szorgalmas, és épp úgy akar, mint én. Ezért én erre nem is gondolok, csak egyszerűen megcsinálok mindent, amit az edzőim mondanak. Mert keveset tudok még nagyon a sportból, de azt mégis, hogy elsősorban rajtam múlik, hogy jó tornász leszek-e, vagy…

És megrántja a vállát, rám bízza a befejezést. Köszön, fogja a „cucc-táskásárt”, és rohan haza tanulni. A ,,vagy”-on azonban én sem gondolkodom. Biztos, hogy Kriszti nagyon jó tornász lesz…

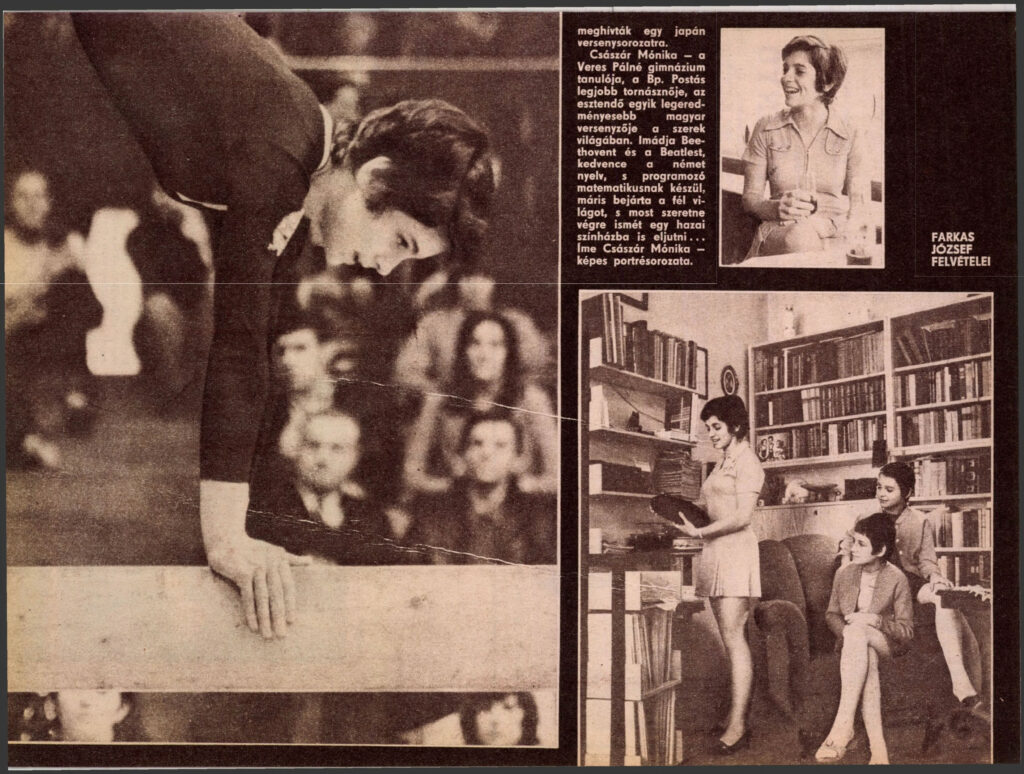

Monika Császár

Note: Sometimes, Monika’s first name is spelled with an accent over the o (Mónika). In other places, it is not.

Pastel Colors

We talked about the ideal competitor types with the coaches. In this imaginary “photo montage,” Ili Békési’s willpower and tenacity, Márta Kelemen’s moxie (in a good sense), Anikó Kéry’s wonderful “legs,” Zsuzsa Matulay’s muscles, Kriszta Medveczky’s age and abandon, Ági Bánfai’s competitive spirit, Gréti Horváth’s sharp mind, Mónika Császár’s poetic moves and flexibility were mentioned.

We usually talk about the ideal only hypothetically. But the facts seem to prove that our gymnasts are skillful and talented, and not many countries can afford to think about the ideal at the competitions.

•

Let’s talk about Monika Császár with a short “o” letter as it stands on her birth certificate. We know her, yet we may not know as much as her skills would require. Her exercises on the balance beam and the floor seem almost artistic with a high level of strength, it’s continuous, smooth, chic, and feminine. She is a calm competitor, she can deliver at the competitions as well, and she doesn’t have bigger “mishaps” in the events she prefers. It’s a calming experience to watch her, but it is also true that, in today’s women’s gymnastics, the shocking programs, the enhanced acrobatics, and the sparkling performances are the things necessary to be called an excellent gymnast. But as long as there is gymnastics in sports one has to be prepared for the different kinds of performers.

What could be the reason for the fact the selectors did not pay attention to her before? Well, it may be because of the pastel color gymnastics she seems to represent.

•

It’s not the name that defines a person, but we are still inclined to some associations. And we seem to imagine Mónika just as she is.

She is quiet with a pleasant demeanor. Smart and a great student. So far, she only had A’s in her reports, but now at the end of the third she has a B from Chemistry in the Veres Pálné Grammar School, but she doesn’t like it when we say that it is no joke to have an exam in the morning and then give her best at a championship in the afternoon. She is humble — maybe a bit too humble. Her answer to this is that Ili Békési is even more humble and tougher than her because she can do gymnastics with the extreme pain she feels in her elbows. There is no doubt that she does not necessarily want to be in the first row. When I ask her to talk about herself, she talks rather about her four siblings and about the coaches who helped her along the way.

[Note: Veres Pálné Grammar School is one of the most prestigious secondary schools in Budapest.]

•

Her parents wanted her lanky brother to become a gymnast, and then at the age of five, she was the one who got to know this sport at Kaposyné’s gym for kids. She talks about aunt Flóra like an adult talks about their first teacher. From there, she went to Vasas at such a young age that other people had to push the buttons for her on the bus. Bp. Postás was the third station, which is where she competes today. When she talks about her improvement then she mentions Györgyi Balikó the most. In 1968, she won the all-around and three events (only vault was left out) in the pioneer Olympics, and she became the pioneer athlete of the year. The years went by quickly in the junior team, in Gottwaldov [Zlín, Czechoslovakia] at the ORT she won 3rd place on beam, and on the national team, she was introduced against the Czechoslovaks. She got her breakout in Konstanca against the Romanians, where on the beam, she was only 5 hundredths of a point behind the best, Ceampelea. She could not go to Minsk; her leg was in a cast. But from January on, her form became better, she had great results at home and abroad as well, she won 3rd place in the masters, and she was second in two other events.

•

We reach the present day where Sándor Békési and Anikó Ducza form and polish the exercises, which she brought with her from Postás.

— There need to be some improvements on beam and floor exercise, but vaulting is the most critical, where I have a hard time with the stuck landing, on the uneven bar I am still trying to find my rhythm because of the problems I have with flexibility and strength, Sanyi has a tough time with me… — as she evaluates herself.

— With which exercise do you have a chance to reach the finals?

— I am not looking that much ahead, although Vali [Valerie Nagy, the head coach of the Hungarian women’s team and Vice President of the Women’s Technical Committee at the time of publication] said that I should concentrate on beam. But my first concern is that the team has good results.

Népsport, July 4, 1972

Pasztellszínek

Az ideális versenyző típusáról beszélgettünk tornaedzőkkel. A képzeletbeli „fotomontázsban” Békési Ili akaratereje és szívóssága, Kelemen Márta jó értelemben vett vagánysága, Kéry Anikó remek „rugói”, Matulay Zsuzsa izomzata, Medveczky Kriszta kora és önfeledtsége, Bánfai Ági versenyfutorja, Horváth Gréti éles esze, Császár Mónika poétikus mozgása és hajlékonysága szerepeltek.

Az ideálisról általában feltételes módban beszélünk. A tények valóságos világa viszont azt mutatja, hogy ügyesek, tehetségesek a mi tornásznőink, s kevés ország engedheti meg magának, hogy a megméretésnél az ideálist helyezze az egyik serpenyőbe.

•

Beszéljünk most Császár Mónikáról, így rövid o-val a keresztnevében, ahogy az anyakönyvi kivonatban szerepel. Ismerjük őt, s talán mégsem tudunk róla annyit, amennyit képességei megérdemelnek. Gerenda- és talajgyakorlata művészi élményt nyújt, magas erősségi fokú, folyamatos, gördülékeny, sikkes és nőies. Nyugodt versenyző, hozni tudja a versenyen is edzésformáját, erős szerein nincsenek nagy „fejreállásai”. Őt nézni megnyugtató élmény, bár az is igaz, hogy ma a női tornavilágban a sokkoló versenyprogramra, a felfokozott akrobatikára, a sziporkázó előadásmódra nyomják az igazi klasszistorna bélyegét. De amíg létezni fog a torna a sport arénáiban, addig egymástól különböző stílusokkal is számolni kell.

Mi lehet az oka annak, hogy viszonylag későn irányult rá a válogatók figyelme? Talán bizonyos fokig éppen ez a pasztellszínű torna és képviselőjének egyénisége.

•

Nem a név határozza meg az embert, mégis hajlamosak vagyunk az asszociációkra. És a Mónikát valahogy éppen olyannak képzeljük, amilyen ő.

Halkszavú és kellemes a modora. Okos és kitűnő tanuló. Mindeddig csak ötöst ismert a bizonyítványban, most harmadikban év végén csúszott be egy négyes kémiából a Veres Pálné Gimnáziumban, de elhárítja, amikor azzal akarjuk magyarázni: nem gyerekjáték délelőtt vizsgázni, délután pedig a szereken a legjobbat nyújtani a mesterfokú bajnokságon. Szerény — talán túlságosan is. Az a válasza rá, hogy Békési Ili sokkal szerényebb és keményebb is, mint ő, mert képes kegyetlenül fájó könyökkel is tornázni. Kétségtelen, hogy nem akar mindenáron elől állni a sorban. Ha róla magáról kérdezem, szívesebben beszél négy testvéréről és azokról az edzőkről, akik pályafutásában segítették.

•

Nyurga bátyjából akartak szülei tornászt nevelni , s ő lett az ötéves korban Kaposyné gyerektornáján ismerkedett alapfokon ezzel a sporttal, s úgy beszél Flóra néniről, mint a felserdült ember az első tanítónőről. Onnan a Vasasba vezetett az útja még abban a korban, amikor más nyomta meg helyette az autóbusz jelzőgombját. A harmadik állomás a Bp. Postás volt, s az ma is versenyzői otthona. Balikó Györgyi nevét említi legtöbbször, amikor a fejlődésről beszél. 1968-ban összetettben és három szeren (csak ugrásban nem) úttörő-olimpiát nyert, s az év úttörő sportolója lett. Szaladtak az övek ifi-válogatottsággal, Gottwaldovban az ORT-n gerendán szerzett 3. helylyel, tavaly pedig a nagyválogatottban mutatkozott már be a csehszlovákok ellen. A kiugrást Konstanca hozta a románok elleni viadalon, ahol gerendán 5 századponttal maradt el a legjobbnak ítélt Ceampeleától. Minszkbe már nem jutott el , gipszbe került a lába. De januártól már ismét felfelé ível formája, megbízhatóan szerepelt itthon és külföldön, a mesterfokon 3. lett összetettben, két erős szerén pedig második.

•

Itt vagyunk a mánál, amikor a válogatottban Békési Sándor és Ducza Anikó formálja, erősíti, csiszolja a gyakorlatokat, amelyeket a Postásból hozott magával.

— Gerendán és talajon is kell javítani, de főként ugrásban, ahol nehezen megy a biztos beállás, felemáskorláton pedig éppen a hajlékonyságon, meg az erőben jelentkező hiányosságok miatt még mindig keresem a megfelelő ritmust, s nem egyszerű a dolga Sanyi bácsinak … — értékeli tennivalóit.

— Mélyült szeren lehet remény a döntőbe jutásra?

— Nem nézek olyan messzire, bár Vali néni mondta, hogy komolyan gondoljak a gerendára. Én azonban elsősorban a csapat jó szerepléséért szeretnék megtenni mindent.

More on 1972