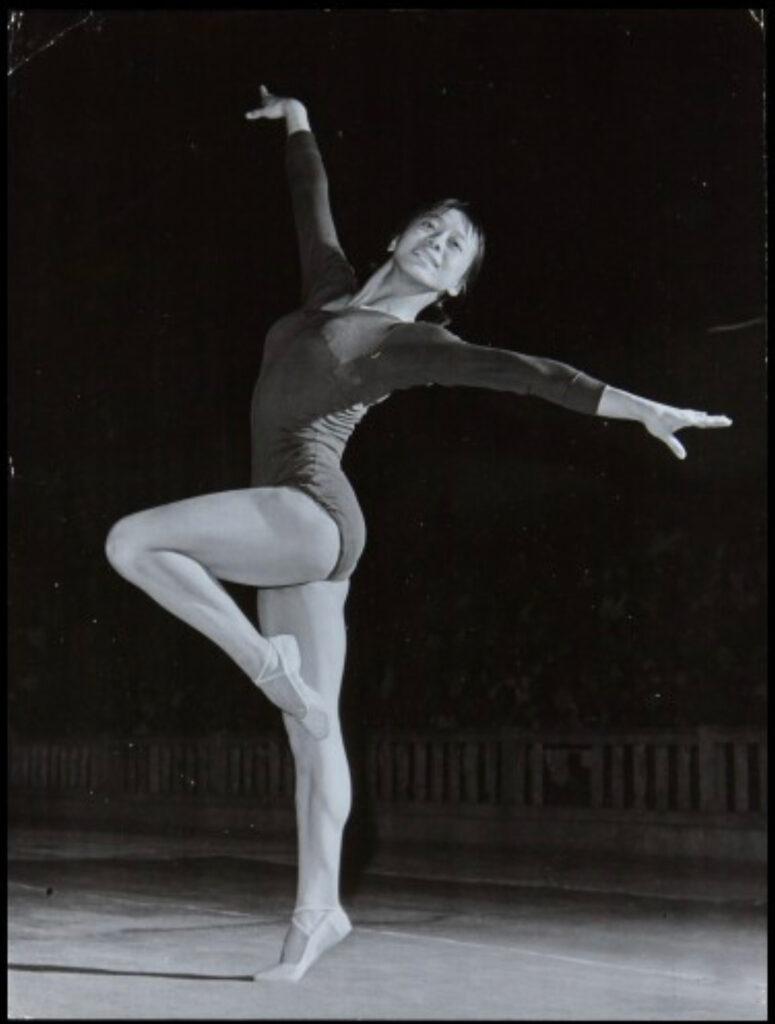

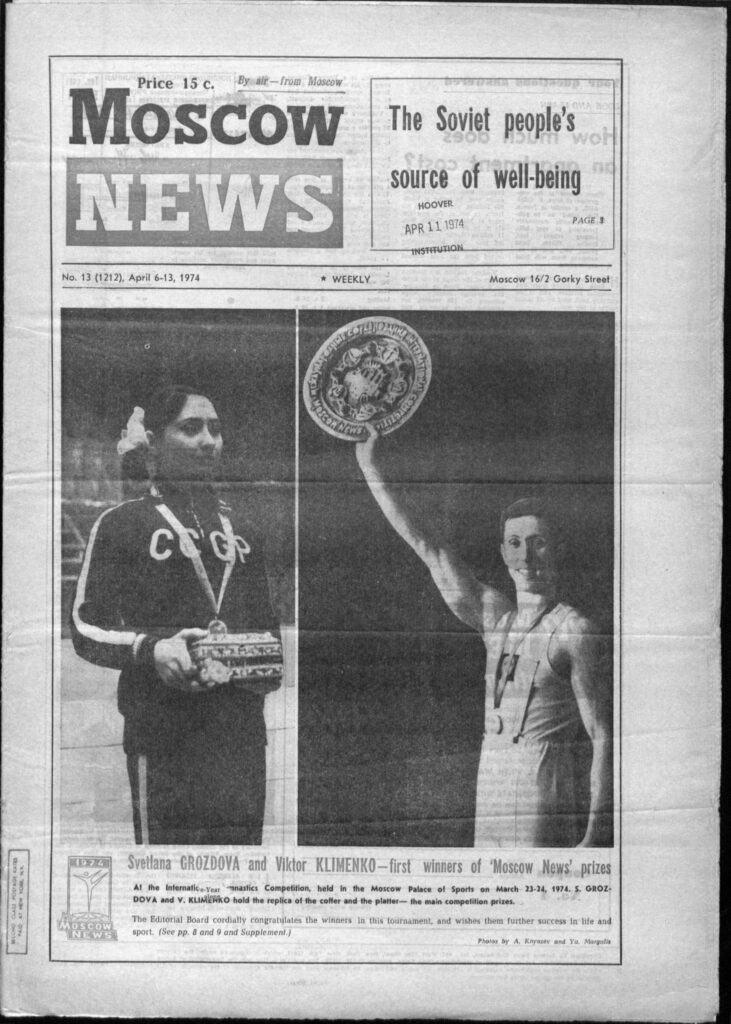

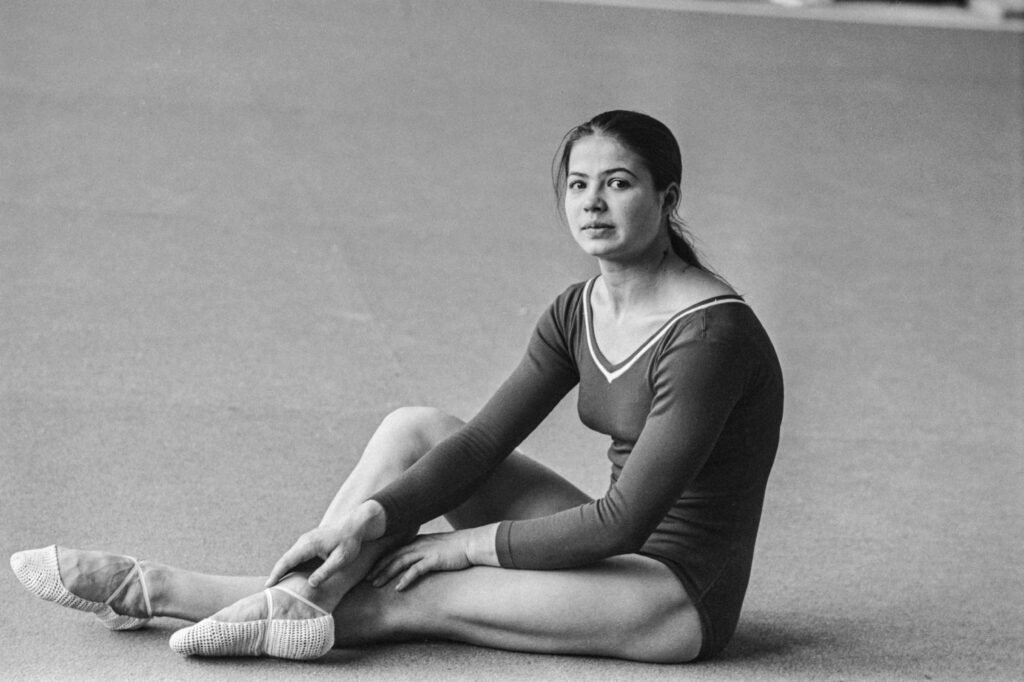

In 1974, Ludmilla Tourischeva won her second-straight all-around title at the World Championships and proved what some, including head coach Larisa Latynina, believed to be true: Tourischeva would always trump Korbut in the all-around.

One month before the World Championships, the Soviet magazine Yunost published an article about Tourischeva and Korbut. Here’s an excerpt:

“Can Korbut finally win against Tourischeva?” they ask.

My answer is: “No, she can’t.”

On one apparatus – sure she can. On two. On three. But not in the big all-around with twelve apparatus (three times four), where the main title of the all-around champion is at stake.

Latynina once put it well into words: “Korbut will surprise, but Tourischeva will win.”

You have to be Tourischeva — steel in work, deaf to the temptations of the world, unquestioningly submissive to her own will as well as her coach’s. Tourischeva is a stayer, she possesses an ideally patient and stubborn all-around character.

And Olya Korbut is a person-explosion, a person of moods. Imagine a sprinter running ten thousand meters — this is Korbut in the all-around.

Stanislav Tokarev, Yunost, September, No. 9, 1974

That said, Korbut, among others, felt that the judges had crowned Tourischeva as the champion even before the competition in Varna began.

Interestingly, the highest score in the competition did not go to either Tourischeva or Korbut. Instead, it went to Annelore Zinke, who scored a 9.95 on bars.

Note: Since there were four judges for each event with the high and low scores being dropped, this meant that two judges gave Zinke a 10.0 for her routine. One 10.0 was dropped, and her counting scores were a 9.90 and a 10.0 for a 9.95 average.

Here’s what happened on Friday, October 25 during the women’s all-around final.

Reminder: This was the first World Championships with an all-around final. (The Munich Olympics were the first Olympic Games to include an all-around final.)

Reminder #2: In 1973, the Women’s Technical Committee tried to ban Korbut’s skills.