In 1972, Cathy Rigby was the “it girl” in the United States. Not only had she won a silver medal on beam at the 1970 World Championships; the American public and media were enamored with her (and her looks). The Tribune out of San Luis Obispo printed:

Cathy Rigby looks more like a windup doll than a world-class athlete. She has a pixie face, large brown eyes, and her blond hair is usually tied in bows. Furthermore, she is only 4’11”, and weighs a mere 92 pounds, a stature that earns her the title “Peanut” from her coach, Bud Marquette, of the Southern California Acro Team of Long Beach. At 19, Cathy may be the finest all-around female gymnast in the world.

May 6, 1972

Famously, Rigby posed nude for Sports Illustrated in 1972 — a move that received backlash from both the FIG and her fellow teammates on the Olympic team. Linda Metheny reportedly was not pleased with the photos. The Dispatch out of Moline, IL, wrote:

There is even an interesting little squabble taking place among members of the United States women’s gymnastics team. Linda Metheny of Champaign, Ill., and Cathy Rigby of California are vying for the honor of being known as the nation’s outstanding female gymnast, and they aren’t friendly. When Miss Rigby’s nude photo appeared in a gymnastics pose in Sports Illustrated magazine this weekend, Miss Metheny — and presumably others — took offense.

At least that isn’t a political issue, and the gals may have scratched at each other and fought that issue out on the weekend plane ride to Germany.

The Dispatch, August 21, 1972

Even before the photos came out, the topics of nudity and gymnasts’ bodies were discussed in the same breath. In an article about the U.S. women’s performance in a dual meet with Japan, Ginny Coco stated:

“You want all the curves to be there in the right places,” said Mrs. Ginny Coco, women’s coach for the meet here, “but not at the level Hugh Hefner might want for the Playboy image. Voluptuous girls don’t win in gymnastics. You want lean, strong girls, the race horse type.”

Warren Times-Mirror and Observer, Feb. 3, 1972

When the articles focused on Cathy Rigby’s gymnastics rather than her appearance, they tended to portray her as a fearless trickster, who had a knack for learning skills quickly.

Here’s a small collection of profiles on Cathy Rigby from 1972…

Note: The articles below will mention Rigby’s weight and eating habits. Rigby would later discuss her struggles with bulimia.

Quick Links:

- Joyous, Bouncy Lot of Teenagers on United States Gymnastic Team

- Top U.S. Woman Gymnast Has Minimal Fear Factor

- Fearless Whirl on a 4-Inch Beam (Life)

- Sugar and Spice — and Iron (Sports Illustrated)

- Foot Injury Puts Cathy Rigby Out of U.S. Gymnastic Trials

- Note: Rigby was injured during the Olympic Trials, but she was voted onto the team. (Rigby is part of a long line of U.S. gymnasts who were added to teams through alternate paths.)

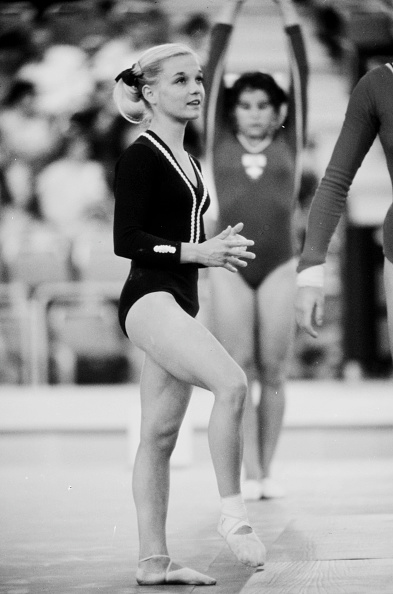

- As you can see in the photo above, her foot was still taped in Munich.

Joyous, Bouncy Lot of Teenagers on United States Gymnastic Team

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Blonde ponytail held by a ribbon of pink yarn. America’s best-known gymnast scuffed her practice slippers in resin and stepped nimbly across a blue mat to the balance beam.

“Now you’re going to see something, “ said B. D. Marquette, the personal coach of Cathy Rigby. “The balance beam makes ‘em or breaks ‘em. You can always throw a fairly decent vault. You can stay on the bars. In floor exercises, you can run a dance. It’s the balance beam that tests ‘em.”

With what seemed like one fluid motion, Cathy was up onto the beam in a flash of blue leotards, as effortlessly as a bird flitting to a higher branch. A simple leap, straddle, and press handstand had put her in standing position on the 16-foot-long, 4-inch-wide beam of laminated fir 4 feet above the mat-cushioned floor.

It was Friday, and nearby other teenage female gymnasts who will represent the United States in this year’s Olympics practiced for a weekend match here at Penn State’s Recreation Hall with Japan’s celebrated national team.

The United States National Gymnastic Squad won the women’s competition and lost the men’s as the two-day match with Japan ended Saturday night.

The Japanese men beat the Americans 286.20 points to 277.90. In the women’s events, the Americans, led by Cathy Rigby, defeated the Japanese 188.95 to 187.20.

At 19 Cathy Rigby of Long Beach, Calif., who won the balance beam and all-around events and tied for second in the floor exercise in the weekend meet, probably will be the oldest of the six American girls selected to compete in Munich.

They are a joyous, bouncy lot, some of them as young as 14 and still wearing braces on their teeth. They practice as much as seven hours a day, totally committed to a glamorous but relatively neglected sport that combines gym class sweatiness with daring circus showmanship and ballet elegance. They need little or no makeup, and they have just the right amount of curves.

“You want all the curves to be there in the right places,” said Mrs. Ginny Coco, women’s coach for the meet here, “but not at the level Hugh Hefner might want for the Playboy image. Voluptuous girls don’t win in gymnastics. You want lean, strong girls, the race horse type.”

Though only 4 feet 11 inches tall and 96 pounds, Miss Rigby meets the requirement of evenly distributed curves. She’s also the team’s most relaxed member, the girl with the minimal fear factor.

On Friday, Cathy won the uneven parallel bars on the opening program, sharing applause from a standing-room crowd of 7,200, including such legendary Japanese stars as Akinori Nakayama, a triple gold medal winner at the 1968 Olympics.

Sixth on the balance beam in the Olympics at Mexico City and second in that event at the 1970 World Championships, Miss Rigby reflects the leaps and bounds progress American gymnasts have made in recent years.

“We’ve bot [sic] 10 times as many kids competing in gymnastics as some of the countries that beat us,” said Gene Wettstone of Penn State, the national coach this year. “The trouble is, our kids are scattered all over the place, training under different coaching systems. The other countries trap their best gymnasts.”

Wettstone sees Japan easily winning its fourth straight Olympic men’s team title at Munich. With the Soviet Union second and North Korea third. He gives the United States men an outside chance for fourth, and thinks the women could finish third back of the Soviet Union and East Germany.

One of the major reasons is Miss Rigby, who demonstrated her maneuvers on the balance beam in practice on Friday afternoon. First, an aerial walkover, twisting in a slow pinwheel without using the hands. Then back handsprings, one-arm walkovers, a needle scale, and whip handstand, straddling the beam with legs at right angles to the torso before whipping the legs straight into the air with a handstand. Finally, a one-and-one-half-twisting aerial dismount.

“Good,” said Marquette, moving over to massage his protege’s neck muscles.

Cathy spit delicately on the palms of her hands, rubbed more chalky magnesium into them, scuffed her slippers again with resin. “You have to have it kind of sticky in this game. You can’t afford to slip.”

Kim Chace wandered over, a 16-year-old from Palm Beach, Fla., rubbing her swollen finger. “Oh, gross! I think it’s infected. I think there’s pus in it.”

The difficulty would not prevent Kim from competing in Friday night’s opening program of the international match. Pain, fear, and fatigue are a routine part of the gymnast’s world.

“They’re subjected to pain on a daily basis,” said the coach, Mrs. Coco. “They get blisters on their hands, the blood runs out. They pull muscles, rip skin, crunch joins, sprain things. After all, gymnasts have the greatest range of movement in sport.”

In Mrs. Coco’s opinion, the result is worth the pain. “Gymnastics means grace and beauty and body control. It’s artistic, and the women’s events are quite feminine. But we have a cultural problem. Parents would rather have their daughters taking ballet or music lessons. We’ve got to convince them that this is not a joke thing for women.”

The women’s events, stressing gracefulness more than sheer strength, are the balance beam, the sidehorse, the uneven parallel bars, and the floor exercises that combine tumbling and dance. The men, required to demonstrate considerable strength as well as coordination, compete in the [long-horse], floor exercises, pommel horse, rings, parallel bars, and horizontal bar.

Every gymnast must take part in every event, and there is a special all-round title for the highest combined scorer.

“Girl gymnasts show much more personality variations than the men,” said Dr. Joseph Massino, the team’s psychologist.

Warren Times-Mirror and Observer, Feb. 3, 1972

Top U.S. Woman Gymnast Has Minimal Fear Factor

LONG BEACH, Calif. (AP) — Cathy Rigby, blonde pigtails flying, cartwheels on a four-inch-wide beam of wood and hurls her 90-pound body around rods of steel.

This 19-year-old, 4-foot-11 fearless female is the greatest hope the United States has had for its first Olympic medal in women’s gymnastics.

“Her fear factor is so minimal,” said Coach Bud Marquette. “That’s what makes her so good. Just… It’s unbelievable. Maybe it’s born in her, who knows? It’s just one of those things.”

She’s not afraid of anything he asks of her on the balance beam or the uneven parallel bars.

“First time and she’ll do it,” he said. “There’s no hesitation. Other girls will stand up there and say, ‘Oh, I don’t know.’ They’ll chicken out. They’ll start crying. It might be three weeks before they’ll even try it.”

“One of the biggest things you have to overcome in gymnastics is fear or you just don’t get very far,” said Cathy, who dropped out of college to devote seven hours a day to working out at a small gym.

Cathy, who lives at home with her parents, a younger brother, a younger sister, a cousin, and a menagerie that once included a snake and monkey, enrolled in a city recreation gymnastics class when she was 10.

She was 14 when she first competed internationally, a pre-Olympics meet in Mexico. Although she made the Olympic team, she was only an alternate in the finals.

However, two years ago, she took home a silver medal in balance beam competition from the World Games in Yugoslavia—the first international medal for a U.S. woman in the sport.

[Note: This is not exactly true. The U.S. women’s team won bronze at the 1948 Olympic Games.]

Marquette said he knew Cathy was something special three months after she joined his recreation department program.

“She’s a pro as far as I’m concerned,” he said. “She’s the best I’ve had. Oh, by far.”

Cathy is optimistic about her chances for a medal at the Munich Olympics but remains realistic.

“There’s a lot of things involved,” she said. “You don’t see a lot of your competition sometimes. Balance beam is difficult. It’s easy to fail anytime. It’s unpredictable a lot of the time.

“But as far as our chances, it’s the best chance we’ve had since gymnastics started, I think.”

Daily workouts with only an occasional Sunday to herself sometimes become a chore, admits Cathy, now a veteran of 11 international competitions.

“But then I remember I have a big competition coming up at the end of the summer and I have to practice,” she said.

Besides, her coach won’t allow her to relax.

“Once you think you’ve got your routines down, he starts finding things wrong with everything,” she added.

Cathy sits through about four interviews and photo sessions a month. Marquette welcomes the exposure “hard to come by for a minor sport.

“She’s been very fortunate because she is very photogenic and a pretty kid, but it hasn’t affected her ego in any way. If it does, I’ll just have to turn her over my knee.”

After practice, Cathy cooks dinner for her family each night.

“Cooking is my hobby, and my mother and father both work,” she said. “I don’t see them, and they don’t see me too much, but they try to help me.”

Her father is a laid-off aeronautical engineer who does odd jobs for the city of Long Beach. Her mother is a calculator for an aerospace firm.

“I do get to travel around a lot and meet people from different countries,” Cathy said. “That’s a social life. I think I’d rather do that right now than go to a dance or something like that.”

Although Cathy appears more like 16 than 19, she “is mature competitively,” said Marquette. “When she’s geared up for a meet, you can’t touch her with a 10-foot pole.

“The judges like her because she’s a good picture of a girl. She’s very feminine and well-mannered.”

Cathy said she might return to college after the Olympics to study physical education or public relations. She wants to have her own gymnastics school.

Meantime, she said, “I have to work on my compulsories—a set routine everyone does—and I just have to be steady. I can’t have any wiggles or wobbles or any kind of break in my routines.”

Ron Roach

The Morning Call, April 2, 1972

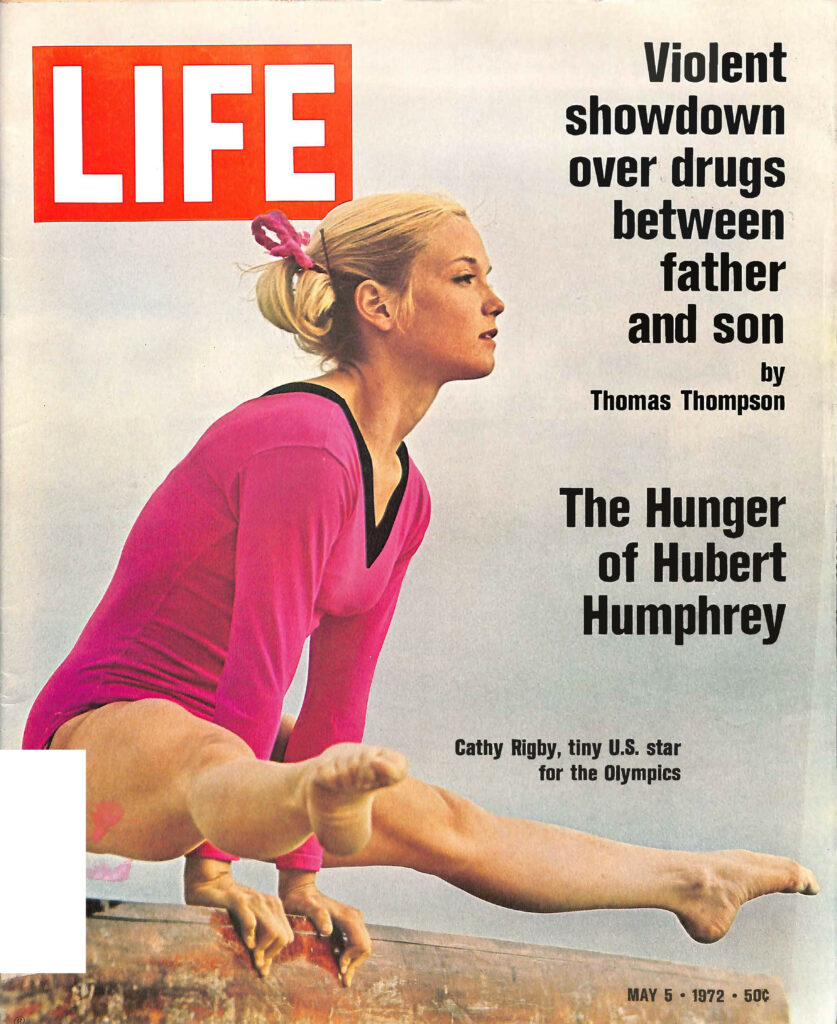

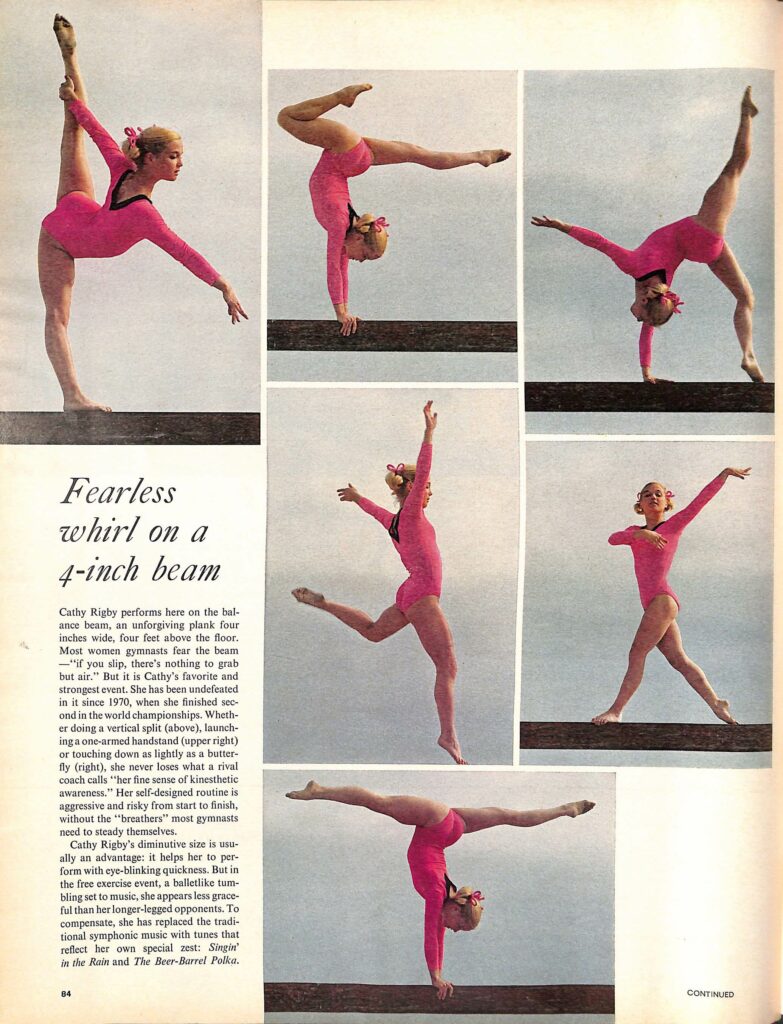

Fearless Whirl on a 4-Inch Beam

Cathy Rigby performs here on the balance beam, an unforgiving plank four inches wide, four feet above the floor. Most women gymnasts fear the beam — “if you slip, there’s nothing to grab but air.” But it is Cathy’s favorite and strongest event. She has been undefeated in it since 1970, when she finished second in the world championships. Whether doing a vertical split (above), launching a one-armed handstand (upper right) or touching down as lightly as a butterfly (right), she never loses what a rival coach calls “her fine sense of kinesthetic awareness.” Her self-designed routine is aggressive and risky from start to finish, without the “breathers” most gymnasts need to steady themselves.

[Note: The photographs mentioned in the paragraph above appear below.]

Cathy Rigby’s diminutive size is usually an advantage: it helps her to perform with eye-blinking quickness. But in the free exercise event, a balletlike tumbling set to music, she appears less graceful than her long-legged opponents. To compensate, she has replaced the traditional symphonic music with tunes that reflect her own special zest: Singin’ in the Rain and The Beer-Barrel Polka.

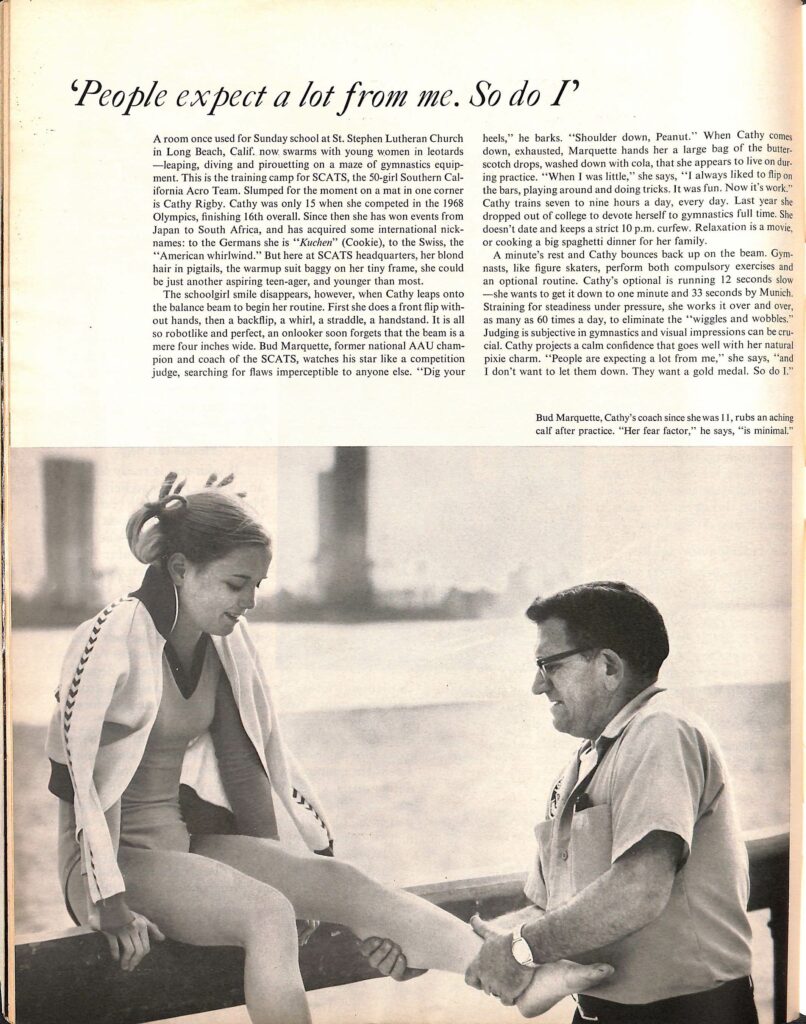

A room once used for Sunday school at St. Stephen Lutheran Church in Long Beach, Calif. Now swarms with young women in leotards — leaping, diving, and pirouetting on a maze of gymnastics equipment. This is the training camp for SCATS, the 50-girl Southern California Acro Team. Slumped for the moment on a mat in one corner is Cathy Rigby. Cathy was only 15 when she competed in the 1968 Olympics, finishing 16th overall. Since then she has won events from Japan to South Africa, and has acquired some international nicknames: to the Germans she is “Kuchen” (Cookie), to the Swiss, the “American whirlwind.” But here at SCATS headquarters, her blond hair in pigtails, the warmup suit baggy on her tiny frame, she could be just another aspiring teen-ager, and younger than most.

The schoolgirl smile disappears, however, when Cathy leaps onto the balance beam to begin her routine. First she does a front flip without hands, then a backflip, a whirl, a straddle, a handstand. It is all so robotlike and perfect, an onlooker soon forgets that the beam is a mere four inches wide. Bud Marquette, former national AAU champion and coach of SCATS, watches his star like a competition judge, searching for flaws imperceptible to anyone else. “Dig your heels,” he barks. “Shoulder down, Peanut.” When Cathy comes down, exhausted, Marquette hands her a large bag of butterscotch drops, washed down with cola, that she appears to live on during practice. “When I was little,” she says, “I always liked to flip on the bars, playing around and doing tricks. It was fun. Now it’s work.” Cathy trains seven to nine hours a day, every day. Last year she dropped out of college to devote herself to gymnastics full time. She doesn’t date and keeps a strict 10 p.m. curfew. Relaxation is a movie, or cooking a big spaghetti dinner for her family.

A minute’s rest and Cathy bounces back on the beam. Gymnasts, like figure skaters, perform both compulsory exercises and an optional routine. Cathy’s optional is running 12 seconds slow — she wants to get it down to one minute and 33 seconds by Munich. Straining for steadiness under pressure, she works it over and over, as many as 60 times a day, to eliminate the “wiggles and wobbles.” Judging is subjective in gymnastics and visual impressions can be crucial. Cathy projects a calm confidence that goes well with her natural pixie charm. “People are expecting a lot from me,” she says, “and I don’t want to let them down. They want a gold medal. So do I.”

Life, May 5, 1972

Photographs: John Dominis

You can order the photos on art.com.

SUGAR AND SPICE—AND IRON

Gymnastics may be the one sport—diving might be the other—which should be performed in the nude. Gymnastics is simply and wholly grace, beauty, strength, a glorification and exaltation of the human body. Thus, Cathy Rigby, the best U.S. Hope for a medal at the Olympics

A week before the final Olympic women’s gymnastic trials in Long Beach, Calif., Bud Marquette, coach of the Southern California Acro Team—or SCATs—whose best and most publicized member is Cathy Rigby, received an anonymous letter.

It read in part: “PLEASE quit cramming Rigby down our throats! To you, she is your baby, to us, she is just another gymnast—nothing more. You have built her up so—big, it is getting to be pretty ridiculous….

“We, as a group…are planning a trip to Long Beach, but for God’s sake don’t ruin our trip by making the competition a one-deal thing—namely, Rigby. Remember, there IS Metheny, Pierce, and Chace. Where does that leave Rigby…? It would be too bad if she broke a leg, etc.—what would you do then…? Rigby is a smart aleck. She can’t even speak to people anymore. You have made her that way…. You should teach your team (what team?)…respect for other people. They walk out on the floor and think they can take over any piece of equipment….

“As far as we are concerned, Metheny will be (and is) No. 1—but, with the politics involved, I imagine Rigby has already been nominated.

“We will be there—and watching. Maybe Rigby will break her big toe—oh, too bad.”

—A group of FED-UPS

Last March, Cathy Rigby won the semi-final Olympic Trials at Terre Haute, Ind., beating Linda Metheny, a 25-year-old veteran of two Olympics. Last May, in the finals at Long Beach, she fell during her dismount in the compulsory bar exercises on the second day of competition. As usual, she stalled her straddle on the high bar longer than anybody else, but this time too long. Her toe slipped under the bar and she fell 7½ feet headfirst. The spotter, who was on his knees instead of standing ready to catch, was able to put a hand on her and save her neck. Cathy had never fallen on her dismount before. Instead of 9.8 points she received 8.3 and lost her lead to Linda.

On the third day she made up points in each event, regaining the lead on the beam when Linda lost her balance. Then, in the floor exercises, the last event of the day, Cathy started out with an Arabian, a half-turned front flip. “When I landed, I heard something pop in my ankle,” she says. “It didn’t hurt right away, but I felt weak, I couldn’t really push.” When the event was over, she was still in first place by one-tenth of a point. She limped off the floor and was taken to a hospital where X rays revealed she had pulled the ligaments in her right ankle. She could not compete on the fourth and final day. Roxanne Pierce won the trials, Metheny was second, Kim Chace third. After deliberating, the U.S. Olympic Gymnastics Committee decided that Rigby would be one of the six regular members on the Olympic team. One week after the trials, she was training again.

Bud Marquette likes to say about Cathy, “I never had anyone like her, and I guess I’ll never find another one, either. She is the typical little American girl. A nice, clean kid. The American ideal. Something like Shirley Temple.”

Cathy’s palms are calloused from working out on the bars. She picks at the calluses and she bites her nails. “I can’t wear rings,” she says, “because my hands are so ugly.”

“She sucked her thumb until she was 11,” says her mother.

Cathy Rigby falls asleep on airplanes and jerks in her seat. “I dream about my routines,” she says, “and I guess I jerk when I fall.”

Ostensibly, Cathy has not been allowed to date until after the Olympics, but this week she disclosed her engagement to Tommy Mason, 33, the former All-Pro running back who now plays for the Washington Redskins. “I met him two years ago,” Cathy says. “We hardly ever went out. We always had dinner at home with my parents. I thought Bud didn’t know, and I was afraid to tell him.”

“I’ve known about it for nearly a year,” says Marquette. “The other day we had a real good daughter-daddy talk and I said, you have to bring it out into the open, but it can’t interfere with your training. Since we had that talk her workouts have been out of sight.”

Cathy will not see Mason again until after the Olympics. “He’s in training camp,” she says, “and he has a 10 o’clock curfew, too.”

In June, 1971, Cathy graduated from high school where she had a B average. She briefly attended Long Beach City College. “If you go to school you have to get up so early,” she says.

When she was a child, her parents wanted her to play the piano. “I was supposed to practice one hour a day,” she says, “but I could never sit still for that.”

Cathy Rigby trains eight hours a day, seven days a week. Because of her total commitment to gymnastics, her “great control over mind and body,” as one teammate puts it, and her lack of fear—complemented by the coordination without which no one should ever try a flip-flop—she has, at age 19, become the finest female gymnast in the U.S. Four years ago, at the Mexico City Olympics, she was suspected of being merely the mascot of the American team; she is 4’11”. At Munich she will be a contender in two of the four women’s events and America’s No. 1 hope for an individual gold medal on the beam or the bars or both. “In 1968, it was all fun and games,” says Cathy, who placed 16th in the all-around. “This time it’s serious business.”

Cathy is the third child of Anita Rigby, who is Cathy’s size, and Paul Rigby, who is 6’1″. Cathy was born two months prematurely on Dec. 12, 1952. At birth she weighed four pounds. She had collapsed lungs, and during the first five years of her life she was often critically ill with bronchitis and pneumonia. “We almost lost her several times,” says her mother, “but she always came back. Cathy and I are very close and a lot alike. I don’t admit defeat in anything, and neither does she.”

Cathy roller-skated when she was 18 months old. At five she wanted to ride a bicycle but could not stay on. “She fell off all the time,” says Mrs. Rigby, “but she never gave up.”

When the SCATs compete away from home, Cathy’s teammates like to go to a movie on the eve of the competition. She prefers to watch television in her hotel room and eat candy. She likes Milk Duds and M & M’s.

“Cathy has a list of things she wants to do after Munich,” says Mrs. Rigby. “She wants to go skiing and horseback riding, and she wants to make a quilt.”

“After the Olympics I might try skydiving,” says Cathy. “That would really scare me. They would probably have to push me out of the plane, and I would hope they’d push me. You know Bud would already have told everybody, ‘She can do it.’ “

Marquette frequently talks with amazement of Cathy’s lack of fear. “When she does a trick,” he says, “she never stops halfway. She always follows through. I could tell her to jump out of a fifth-floor window, and she would do it. Of course, she would expect me to be there to catch her.”

Cathy Rigby weighs between 89 and 93 pounds. Her measurements are 32-23-31. She has 17″ thighs. She wears a size three junior petite. Marquette calls her “Peanut” or “Shrimp.”

“He doesn’t want me to grow up,” says Cathy.

“It changes the center of gravity,” says Marquette, “and she may never regain her former sense of balance. Cathy still looks the way she did nine years ago when she joined the SCATs.”

If Cathy Rigby had to write a composition entitled “What Gymnastics Means to Me,” it would read like this: “Gymnastics has been my whole life. The best of it is that it has kept me from being bored. It has helped me set goals for myself and become a better person. Because I have to discipline myself and go down to the gym every day, I am happy with myself. It also helps me to do something for other people—for my coach and my family. I can make them be happy with me. I am getting an education out of it, just by being able to see what goes on in other countries, instead of reading about it. Because of gymnastics I am probably, right now, living the best part of my life. I don’t think I will ever get a chance again to do as much as I do now.”

However, she never had to write such a composition, which is the penalty imposed by Marquette upon any SCAT “who breaks the contract.”

Marquette has set up such obvious rules as “no alcoholic beverages” and “no smoking,” but the contract also includes a 10:30 p.m. curfew which is sometimes hard to observe. Therefore, he makes a point of calling up parents at night to make sure their daughters are home. “There is never any trouble with Cathy,” he says.

Journalists have called Cathy Rigby “Pixie,” “Kewpie doll” and “Barbie doll,” much to her embarrassment. Still, since her blonde hair began to darken, she has dyed it regularly “to keep up the image” she says. “I would like to let my hair grow, but Bud wouldn’t let me.” Long hair is frowned upon by gymnastics judges. Cathy keeps her pigtails pinned back and fastened so tightly with ribbons that she gets headaches.

Cathy used to be a specialist on the balance beam. Now she is just as proficient on the uneven bars. In the floor exercises and side-horse vaulting, where taller women have an advantage, she is working on new, difficult moves to compensate for her lack of height.

“I think that Beer Barrel Polka music she has chosen for her floor ex is dreadful,” one coach said recently. “It will be a flop in Europe. It’s just too cute.” Rigby points out that Vera Caslavska of Czechoslovakia, who won four gold I medals in 1968, did her floor exercises to the Mexican Hat Dance. “The Mexicans loved it,” she says, “so I thought the Germans would like a polka.”

In Munich, Rigby’s competition will be East Germany’s Karin Janz and Erika Zuchold and Russia’s Ludmila Turishcheva and Tamara Lazakovitch.

In the 1970 World Games at Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, Rigby won the first medal ever by an American woman, a silver on the beam. She beat Janz in that event and also Turishcheva who became all-around world champion. Cathy has won in Tokyo, Johannesburg and London. Last spring she competed against Russian and Czechoslovakian teams in Riga and won the beam over Lazakovitch. She also placed third in both the bars and the all-around.

Recently, Linda Metheny was quoted as saying, “I beat Cathy every time we competed before the 1968 Olympics, and two out of three since then. Her coach wouldn’t let her compete against me, except when he thought I was ill or injured.”

To read the rest of the story online, head over to the Sports Illustrated website.

Anita Verschoth

Sports Illustrated, August 21, 1972

Foot Injury Puts Cathy Rigby out of U.S. Gymnastic Trials

An injury Saturday sidelined Cathy Rigby, regarded as America’s best hope for its first Olympic gymnastics medals, during the U.S. women’s gymnastic trials at the Long Beach Arena.

Miss Rigby, 19, from Long Beach had been leading the competition when she had to cancel after pulling a tendon in the arch of her right foot Friday night during a tumbling stunt.

She received emergency treatment later and was released from the hospital but her coach ruled against letting her compete in [the] final competition Saturday.

With a margin of less than one point over her nearest competitor, sources said there was no doubt she would finish out of the top six places needed to qualify for the Olympics.

However, Vannie Edwards, chairman of the U.S. Women’s Gymnastics Committee, said a vote was taken permitting Miss Rigby to join the U.S. team. He said she will be considered a regular member of the team and not an alternate. Edwards said now only the top five placers will automatically make the team, as well as Miss Rigby.

With Miss Rigby out of the competition, Roxanne Pierce, a 17-year-old high school student from Kensington, Md., wound up first with a fine score of 151.05 points out of a possible 160. She held off veteran Linda Metheny, who scored well in the evening after a mediocre afternoon performance.

The 25-year-old Miss Metheny, a two-time Olympian, scored two spectacular routines, earning 9.6 on the balance beam and 9.75 — the highest score in four days of competition — in the floor exercise. Her final total was 150.85.

Third was Kim Chace of Riviera Beach, Fla., with 149.65.

Miss Pierce’s scores in the evening were 9.30 on the balance beam and 9.55 in floor exercise.

Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1972

More on 1972