The Soviet Union, like the rest of the world, wasn’t immune to Korbut mania. She appeared in numerous newspaper articles and photographs. The country’s media followed along as the Women’s Technical Committee considered banning Korbut’s famous skills, and the newspaper Izvestiia portrayed Korbut as the star of the Soviet gymnasts’ British tour. There even was a short film about Korbut in 1973. It was titled The Joys, the Sorrows, and the Dreams of Olga Korbut (Радости, огорчения, мечты Ольги Корбут).

Below, you’ll find a small collection of Soviet media about Korbut, including the aforementioned film and an article from Soviet Woman, a bimonthly illustrated magazine out of Moscow.

Note #1: There will be references to Knysh below. It should also be mentioned that Korbut has alleged that Knysh sexually assaulted her. Knysh denied the allegations. He died in 2019.

Note #2: There will be references to weight and weight-shaming in this article.

The Joys, the Sorrows, and the Dreams of Olga Korbut

The Russian-Language Version

The Version with English Subtitles

Like many puff pieces on gymnasts from the time, the focus was on the coach as much as the gymnast. The piece presents Knysh, Korbut’s coach, as a brilliant innovator, and Korbut attributes her success to him in the film, saying:

If there wasn’t Renald Ivanovich, there would be no me. I didn’t quite realize it before.

But the piece doesn’t dive into Korbut’s origins in the sport. As Korbut tells it later in her autobiography, My Story, if it hadn’t been for Olympic champion Elena Volchetskaya, there would have been no Korbut, who was almost passed over. But Volchetskaya selected her to train. In fact, Knysh originally thought that Volchetskaya was wasting her time with Korbut. (More on that subject at the end of the post.)

Interestingly, Soviet Woman published a more complete origin story, including Volchetskaya’s role in Korbut’s early career. The article was published simultaneously in multiple languages, including Russian, English, German, and French. You can find the English version of the Korbut article below.

Note: As we saw with Nadia Comăneci, it was not uncommon to simplify gymnasts’ origin stories in some publications while telling more complete stories in others.

The Soviet Woman Profile

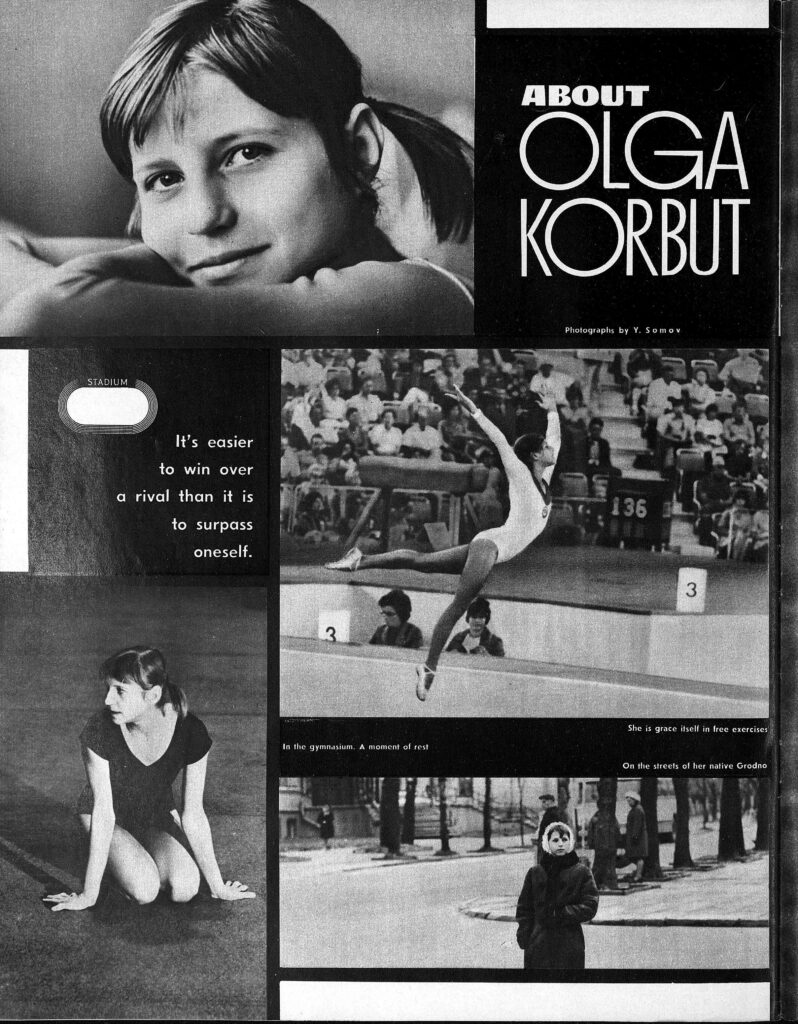

About Olga Korbut

It is customary, when answering a question, to tell everything in sequence. I have to violate this custom here, because chance brought me in contact with Olga Korbut when the successes of this 13-year-old girl in gymnastics were so considerable that she was invited to train together with the members of the USSR National Team. That was four years ago, in Moscow, at the Palace of Sports.

I like to attend these training sessions, to sit on a bench in the farthest corner of the gymnasium and watch how an exercise is repeated ten, fifty, a hundred times. And then, during a competition, when the gymnast smilingly ascends the estrade and, as it seems, playfully performs fantastic flips, turns and leaps—you feel especially keenly the intense will and patience needed by that same gymnast who charms millions of her fans.

Olga attracted attention immediately. Not only because she was a “newcomer,” and not even because of her age—she was a child compared to the leading figures. Olga had an amazing ability to concentrate, was not diverted by anything taking place around her, when time after time she swung from the top to the lower of the parallel bars in an attempt to hang suspended from it, her body for a split second parallel with the mat. An hour before I could not even imagine that anything of the kind could be accomplished, but Olga already clearly pictured the combination from beginning to end with all the flips, turns, and flights from top to bottom bars.

This exercise, born of the fantasy of the gymnast and her trainer, just like a living thing, resisted, and stubbornly refused to turn from a vision into reality.

I know what work in gymnastics means. I have witnessed exploits of diligence. I had the good luck to be present when Larisa Latynina, Natalia Kuchinskaya, Zinaida Voronina and Larisa Petrik were training. Olga works a bit differently. Her work is just as resolute, but it is also so inspired as though she was at a competition and not at a training session.

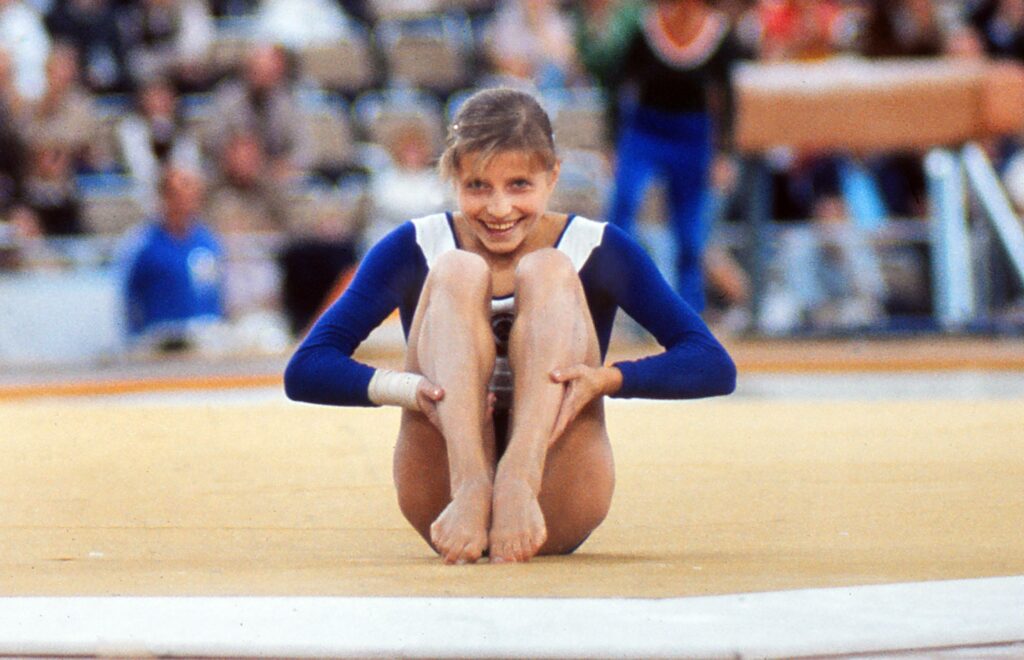

Two years later the many thousands seated in the grandstands of the Palace of Sports (and even the grey-haired, worldly-wise referees) gasped and then broke into stormy applause, when apprehension was replaced by admiration, as a blonde girl, with the emblem of the Byelorussian SSR on her uniform, swung down from the top bar, became stock still, and soared down from under the lower pole like a seagull over the sea. Not a single gymnast in the world had ever executed such a fantastically complicated combination before.

Not only on the parallel bars but also in her exercises on the beam—that most crafty of all apparatus—did she do “the impossible” somersault, amazing everyone by her bold courage. Olga also succeeded in excelling the recognized leaders—Zinaida Voronina and Larisa Petrik—in the vault.

I was again at a training session. Olga was no newcomer in the National Team any more; she was USSR Champion, But everything was just the same. Perhaps her gestures and movements were more finished, more graceful. Now Olga had an added concern—to watch over Nina Dronova, a 13-year-old school girl from Tbilisi. She, just like Olga two years ago, had been invited to train with the members of the National Team. Olga prompted and advised this “Mozart of gymnastics,” who had impudently stormed championship heights without taking into account the titles of her older friends.

Now we were sitting with Olga in the corner of the gym, watching Nina, and Olga was answering my questions.

Yes, she was born in the Byelorussian town of Grodno. Her father is a building engineer. He loves sports very much—he’s an expert shot. Her two sisters—lrina and Zemfira—like volleyball, and her third sister—Ludmila—is also a gymnast. She holds the Master of Sport title. It was Ludmila who brought Olga to the children’s sports school when she was 9 years old. Ex-World Champion Yelena Volchetskaya trained her that first year. Then Renald Knysh, one of the country’s most prominent trainers, took over.

“My teachers impressed on me from the very beginning, before I had learned to somersault or do handstands, that gymnastics. recognizes only one love and demands everything of you. I suppose that’s why the process of training and everyday work attract me as much as competitions do. Only not competing with rivals—but with myself. It’s easier to win over a rival than it is to surpass oneself.”

“What contests do you remember most of all?”

“The Junior Championships of Byelorussia—I was 12 years old then, and the USSR Spartakiade for School Children which took place a year later.”

“You became Champion in the vault, and in exercises on the beam and the parallel bars?”

“Yes. I had a hard time with my free exercises though.”

I call to mind this conversation of 1970 because it gives answers to many questions sent in to our editorial offices and, primarily, about how Olga understands the responsibility a gymnast has towards gymnastics.

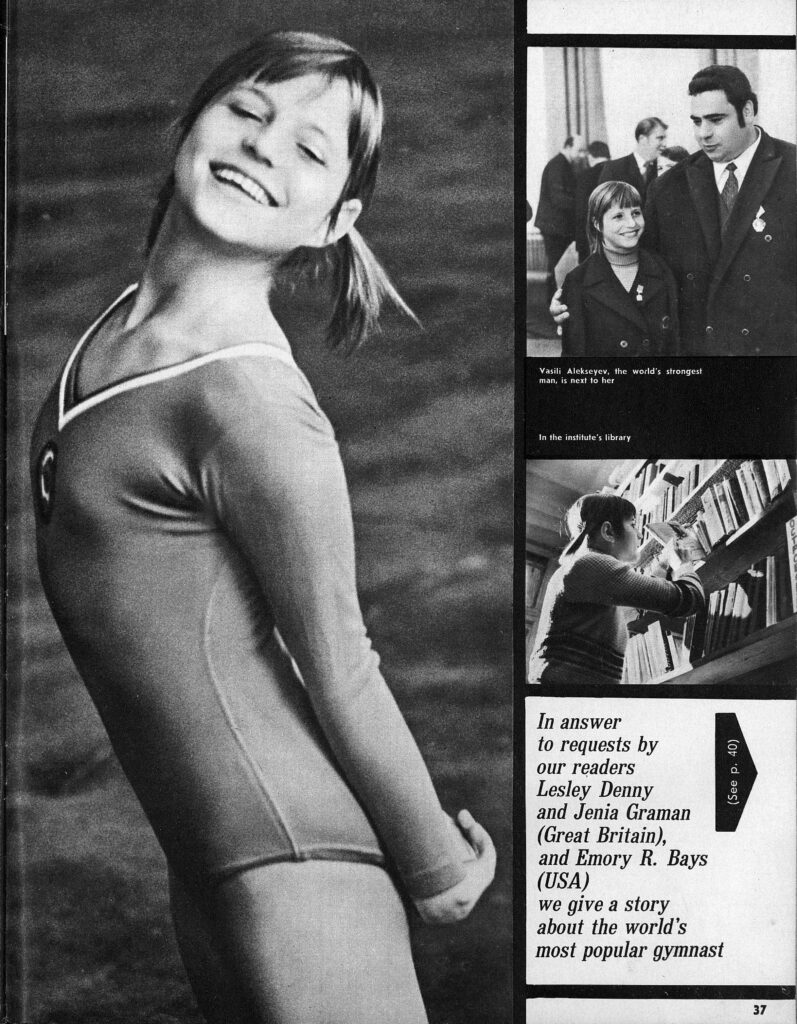

Olga loves sweets but does not indulge in them. She adores the theatre, but time is so short that in the main she looks at plays on TV. But what Olga does really indulge in is books and music. Her tape-recorder is always on at home or in her hotel room during competitions. Her favourite poet is Andrei Voznesensky and her favourite composer—Rodion Shedrin.

The Olympic year was a genuine changing medley of events for Olga. In the beginning she went to Japan. There were three matches held there with Japanese gymnasts, in which Nina Dronova and Ludmila Turisheva took part together with her. In the first match Olga lost the Cup to Nina, in the second—she won, while in the third—she lost again, this time to Ludmila. Then she was not included in the team which represented the USSR at the European Championship. But she created such a brilliant composition of free exercises that she could have easily competed with the best gymnast—Ludmila Turisheva.

Olga’s attitude to victories was as it should be. Defeats did not seem to affect her self-esteem. She remained calm, responsive to her friends in gymnastics and to her comrades in School No. 10 in Grodno where she was studying in the last grade. As before she preferred the humanities, reading one book after another on history, geography, philosophy, and the best-sellers. As for mathematics and chemistry she studied only what was needed.

Just before she left for Munich, Olga came to our editorial offices. I then asked what she thought her performance would be like at the Olympic Games.

“The main thing is that our team should win,” she answered. She did.not say a word about her chances in individual competitions.

The days in the Sporthalle in Munich became Olga’s days. She won in the free exercises, and by the beginning of the contests on the parallel bars she was already a general favourite, the most popular sportswoman at the Olympics! And then—a combination of elements inconceivable for boldness and complexity! The hall knew this and the hall was stunned … and then burst into an ovation even before the exercise was finished. Now a simple shift from the lower to the top bar… and the impossible took place. Her hand slipped on the pole and Olga lost her balance. The TV lens caught this moment in every detail. Olga did not smile, nor did tears fill her eyes. She bit her lip slightly as she does whenever anything is difficult, and continued the combination, finishing it with an unusually risky turn, which had never been done before. There probably is no reason to say what went on at the Sporthalle then! Even the judges, abandoning their impartiality, decided not to pay any attention to her “flaw”—they were enchanted by her brilliant execution of the whole composition. Half an hour later Olga was standing on the highest step of the Olympic podium. And the national anthem of the USSR rang out. She tried to be serious, but could not hide her joy.

The golden glint of the Olympic medals is flattering to their owners. But they are not blinded by it. And if you walk along the streets of Grodno early in the morning you will meet a blonde girl with a student’s portfolio—yes, Olga Korbut is now a student of the faculty of history at the Pedagogical Institute— and she carries a big bag with her sports togs. Every day before lectures she has a training session…

BORIS SEMYONOV

Soviet Woman, no. 13, March 31, 1973

Appendix: Korbut’s Start in Gymnastics

In her autobiography, My Story, Korbut recalls her start in gymnastics. After her first competition, Volchetskaya, 1964 Olympic gold medalist, selected Korbut.

“Weight?” the coaches would ask. “Height? Date of birth? All right, please come to such and such a place at such and such a time…”

It was humiliating. They selected girls the way ranchers choose livestock at a horse auction: examining teeth, tapping at joints, and paying attention to the groin area. Most importantly, though, none of them was paying the slightest attention to me.

Then I had a stroke of luck. Elena Volchetskaya herself, a former Olympic champion – the idol of us all — came up to me and spoke the words I had only dreamed of hearing.

“Well, ‘fatty,’” she said. “Want to go to a sports school?”

My Story

And according to Korbut, Knysh thought that Volchetskaya was wasting her time.

The work at the gym progressed at full swing. I was too young to think about what might happen next, and had no idea that only some of us would be allowed to move on to the advanced group. The rest would be labeled “unpromising,” and forgotten.

Nor did I know that Renald Ivanovich Knysh himself, who supervised all the coaches, saw absolutely no reason to keep me in the school. Ren was strongly against the idea of Volchetskaya wasting her time on me. His reasoning was simple: there was no way to make a gymnast out of this “fatty.”

After he had watched us working for some time, he approached Volchetskaya. “I can’t understand it, Lenka,” he said sternly, but using her nickname. “Why do you keep her? Don’t you have better things to do? Why do you need this dumpling?

“First of all, this ‘small ball’ works like a mule,” Volchetskaya said with controlled anger. “And second, she immediately carries out anything you show her. I won’t expel her.”

The outcome of this ongoing dispute would determine my whole future. I came very close to being expelled from the school, and it is ironic that the person who argued most strongly in favor of it was to become my coach.

My Story

More on 1973

More Interviews and Profiles