In July of 1973, after Viktor Klimenko won his second European all-around title, Stadión, a weekly Czechoslovak sports magazine, published a profile on him. It offers details about his early years in the sport, his rivalries within the Soviet team, his coaching changes, his recovery from an Achilles tear that occurred during the 1971 European Championships, and more.

Enjoy!

Note: You can read a much shorter profile of the Klimenko brothers from 1972 here.

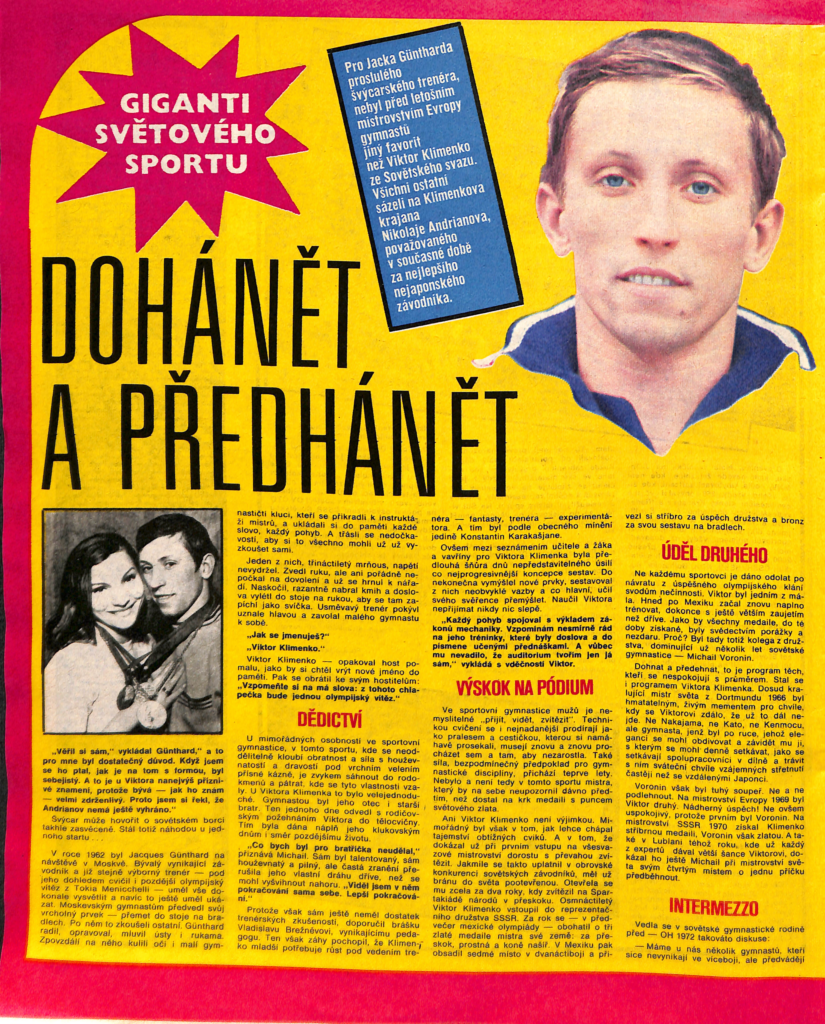

Catching up and Overtaking

“He believed in himself,” Günthard explained, “and that was a sufficient enough reason for me. When I asked him how his form was, he was confident. And that is a most favorable sign in Viktor because he is — as I know him — very reserved. That’s why I said to myself that Andrianov has not won yet.”

The Swiss can talk about the Soviet athlete in such an insider’s way. He happened to be standing at one of the competitions…

In 1962, Jack Günthard visited Moscow. The former excellent athlete and already excellent coach — even the later Olympic champion from Tokyo Menichelli trained under his supervision — was able to explain everything perfectly and he was also able to show it. He showed the Moscow gymnasts his top element — back toss to handstand on parallel bars. After him, the others tried it. Günthard advised, corrected, and spoke with his mouth and hands. From afar, the little boy gymnasts who had crept up on the masters’ instruction kept their eyes on him, memorizing every word, every movement. And they were trembling with eagerness to try it all out for themselves.

One of them, a little boy of thirteen, couldn’t stand the suspense. He raised his hand, but without even waiting for permission, he was already rushing to the apparatus. He jumped up, took a quick swing, and literally flew up to a handstand and stopped there like a candle. The smiling coach nodded his head approvingly and called the little gymnast over to him.

“What’s your name?”

“Viktor Klimenko.”

“Viktor Klimenko,” the guest repeated slowly as if he wanted to memorize a new name. Then he turned to his hosts, “Remember my words: this little boy will be an Olympic champion one day.”

Heritage

It is customary for extraordinary personalities in gymnastics, a sport in which agility and strength are inseparably combined with tenacity and predation under the supreme command of strict discipline, to reach into their family trees and inquire where these qualities came from. In the case of Viktor Klimenko, it was very simple. His father and his older brother were both gymnasts. One day, with his parents’ blessing, he took Viktor to the gym. This set the tone for his boyhood days and the direction of his later life.

“There’s nothing I wouldn’t have done for my little brother,” Mikhail admits. He was talented and hard-working himself, but frequent injuries interrupted his own career before he could rise to the top. “I saw in him a continuation of myself. A better continuation.”

However, since he himself did not have enough coaching experience, he recommended his brother to Vladislav Brezhnyev, an excellent teacher. However, he soon understood that Klimenko Jr. needed to grow under the guidance of a fantasist coach, a coach-experimenter. And this, according to the general opinion, was only Konstantin Karakashyants.

[Note: Karakashyants was Sergei Diomidov’s coach who helped him invent the Diomidov on parallel bars. Mikhail Voronin wrote about Karakashyants in his autobiography.]

However, between the moment when the teacher and the pupil were introduced to each other and the laurels for Viktor Klimenko, there was a long string of days of unimaginable effort to conceptualize the most progressive routines. He was endlessly inventing new elements, assembling them into unusual links, and, most importantly, teaching his athletes to think. He taught Viktor never to accept anything blindly.

“He connected every movement with the interpretation of the laws of physics. I remember his training sessions, which were literally and to the letter sophisticated lectures. And he did not mind at all that I was the only one in the audience,” says Viktor with gratitude.

Vaulting on the Podium

In men’s gymnastics, it is unthinkable to “come, see, conquer.” Even the most gifted ones are pushing their way through the skill like through a forest, and the path they have painstakingly cut must be traversed again and again to keep it from becoming overgrown. Also, strength, a prerequisite for gymnastics disciplines, only comes years later. So there has not been, and is not, a champion in this sport who did not draw attention to himself long before he had a world gold medal around his neck.

Viktor Klimenko is no exception. What made him exceptional, however, was how easily he understood the secrets of difficult exercises. Also exceptional was the fact that he was able to win the first time he entered the All-Union Youth Championships. As soon as he had made his mark in the huge competition of Soviet competitors, the gate to the world was already open. It opened completely two years later when he won the Spartakiad of Nations on vault. Eighteen-year-old Viktor Klimenko joined the USSR national team. A year later — on the eve of the Mexican Olympics — he gained additional three gold medals as the champion of his country: for vault, the floor exercise, and pommel horse. Then, in Mexico, he took seventh place in the all-around and brought home silver for his team success and bronze for his routine on parallel bars.

The Role of the Other

Not every athlete can resist the temptations of inactivity after returning from a successful Olympic event. Viktor was one of the few. Immediately after Mexico, he started training again, with even more dedication than before. It was as if all the medals he had won up to that point were a testament to defeat and failure. Why? Because there was a teammate who had dominated Soviet gymnastics for several years — Mikhail Voronin.

To catch up and surpass, that is the agenda of those who are not satisfied with the average. It has also become Viktor Klimenko’s program. The reigning world champion from Dortmund 1966 [i.e. Voronin] was a tangible, living memento for the moments when Viktor thought he could not go on. Not Nakayama, not Kato, not Kenmotsu, but a gymnast who was close at hand, whose elegance he could admire and envy, with whom he could meet daily, as co-workers meet in the workshop, and spend festive moments of mutual encounter with him more often than with distant Japanese.

Voronin, however, was a tough opponent. He simply would not succumb. At the 1969 European Championships, Viktor came second. A wonderful achievement! But not a satisfactory one, because Voronin was first. At the 1970 USSR Championships, Klimenko won the silver medal, but Voronin won the gold. And also in Ljubljana the same year, where every expert gave Viktor more chances, Mikhail managed to overtake him by one place with his fourth place at the World Championships.

Intermezzo

There was a discussion in the Soviet gymnastics family before the 1972 Olympics:

– We have several gymnasts who do not excel in the all-around, but they show unique elements on individual apparatus. For example, if Katkov from Moscow had been included in the team, he could have won gold in the event final on vault.

– The basis of gymnastics is versatility, execution in the all-around, and without that, no one gets to the finals. If we put together a team of clowns, we could lose our traditional second place. We have to combine one with the other.

– The Japanese don’t have anything particularly original or new either, as we saw recently during the pre-Olympic tour in Japan. They are focusing on the stability of performance.

– Yes, that’s true. However, several years ago, Japanese coaches created routines that were said to be ahead of their time. However, they were already thinking about Munich then and used those few years so that the athletes could gain confidence and sharpen their execution. Now, their routines may be familiar, but in Munich, they will still be the most progressive and also perfectly practiced. When this Olympics is over, they will be reinventing things in Japan.

– We need that kind of perspective too. Today we can catch up with the Japanese in terms of difficulty, but we don’t have time for perfect training.

– So the Japanese will be going for the 1976 Olympics?

– They and others. And we should care about them too.

Step into the Sun

Karakashyants again peppered Viktor’s already difficult routines with additional elements of the highest difficulty. They resembled acrobatic performances. When, after they were polished and polished, Klimenko presented them to the strict European judges, everyone understood that this was the modern concept of gymnastics. Karakashyants’s prescient efforts bore fruit.

But the careful orchardist no longer harvested the fruit together with his disciple. He switched to scientific and pedagogical work at the university, and Viktor returned to the one who had brought him to gymnastics, his brother Mikhail. Both have since become masters of their field, the elder a deserving coach, the younger a star of Soviet gymnastics.

“Many people were afraid that Misha could not be tough with me like Karakashyants was,” Viktor recalls. “That didn’t happen at all. He relentlessly insisted that the routines had to be even more challenging, but at the same time he reminded me of the softness of the exercises, the spectacular finishes, and the purity of the execution.”

Viktor went to Madrid for the 1971 European Championships together with his biggest rival. True, he did not yet have Voronin’s elegance, but he surpassed him in courage, originality, and the riskiness of his exercises. And he deservedly won for the first time over his compatriot and the whole European elite.

Fall and Crutches

After the joyful moment came the drama. The day after he had grasped the European Cup in his hands, he had to go through the six stages of the optional program again, where the medals for the individual disciplines were to be decided. Klimenko was not without a chance here either. However, while warming up for the first of the event finals, he suddenly collapsed on the carpet after a flip. There was silence in the hall as the new overall European champion was carried away on a stretcher.

Doctors diagnosed a ruptured Achilles heel. Few athletes have been able to return to major sports after this injury. Wasn’t Viktor Klimenko supposed to be on the podium? Was this to be the end of his sporting career? At the age of twenty-two?

[Note: There had been a few gymnasts who were able to come back. Ikeda Keiko, for example, returned to the 1966 World Championships after tearing her Achilles, and Kato Sawao won the all-around in 1972 after tearing his Achilles in 1970.]

Klimenko’s leg was in the hands of one of the best sports surgeons, Vladimir Bashkirov, head of the surgical department of the First Moscow Clinic. They say Bashkirov can do the impossible. He did. In addition to helping Viktor to complete anatomical tissue restoration, he restored his faith in his own capabilities. While still in his hospital bed, Klimenko decided to start over.

Ten days after his release from the hospital, Viktor Klimenko could be seen in the gym again. Still with his leg in a cast and on crutches. Two months later he asked — yes, literally asked — to be included in the Moscow team and to compete in at least four disciplines.

“They allowed it. I know it was more out of compassion, out of friendship, because nobody believed in my return at that time,” Viktor says without bitterness. “Only my brother Mikhail, my wife Larisa [Petrik], and Dr. Bashkirov trusted me implicitly. And, of course, myself.”

Eight months after the injury, Viktor started to get back to his former form. When he resumed training in February 1972, he was still shy, but he had already won three gold medals at the USSR Championships. He was thus given complete confidence and, most importantly, a place on the Olympic team.

Victory, Not Just Participation

In Munich, the gymnasts competed for the first time for four days instead of the previous three. This required extraordinary physical endurance. Viktor Klimenko was undoubtedly in the worst situation. His brother and coach, Mikhail, knew this and therefore tried by all means to trick the strict guardians of the Olympic order and sneak up on Viktor to massage his — not injured, but healthy — leg, which was aching after the increased exertion. Moreover, a callus had burst on his palm. A trivial gymnastic injury, but very painful, for which there is only one effective cure — stop training. Was that possible?

Before Klimenko took the final fight on our horse, to fight the favored Japanese Kato and Kenmotsu, he opened the half-healed wound himself.

“It was the only solution for that moment. Otherwise, I would have had to wait, at least subconsciously, for the callus to burst again. This way I had no choice but to accept the pain and I could forget about it,” the athletes have to be tough on themselves.

The pommel horse is a special discipline that has its own criteria. Iron will is no less important in this exercise than physical strength and technique. That is why Boris Shakhlin and Miroslav Cerar won so often on this apparatus. That’s why Viktor Klimenko also won on it. Fourteen months after his injury, he won Olympic gold, proving the strength of his character. He didn’t go to Munich just to be there, he went there to win.

Reprise

Again, however, Klimenko was not the first in his homeland. The Soviet “Japanese” Nikolai Andrianov, with youthful audacity, made his way to the top position and even in Munich settled on the Olympic ranking just behind the Japanese trio. Viktor once again had an opponent at home who would not let him rest even after the Olympics. He only occasionally swapped the gym for the tennis court and stole a few hours from gymnastics for his other great love — soccer. Although he has never had stands of fans cheering him on, eyewitnesses say that the soccer team may have had a second Yevryuzhikhin in him. He could have been the second Yevryuzhikhin, but he hasn’t. Because gymnastics still needs its Klimenko.

For Jack Günthard, there was no other favorite before this year’s European Championships in Grenoble…

It was written in the comments afterward that Viktor Klimenko clearly proved his superiority only on parallel bars with his super difficult routine. He was said to have been helped to the all-around title by Andrianov’s mistakes and errors. However, isn’t the knowledge of tactics, the art of benefiting from the opponent’s wobbles, a part of primacy? Doesn’t maturity help one to become the champion? Klimenko is reaping what he sowed years ago and has been cultivating for years. That’s why, at twenty-four, gymnastics is still his future.

All the more so because today — in the full bloom of his powers — the graduated teacher Viktor Klimenko has also embarked on the path of gymnastics science. The topic of his post-graduate thesis is: “Extremely difficult finishes of routines on rings.”

He lives gymnastics, he lives with a gymnast — Larisa, known as Petrik, was a long-time USSR national gymnast before she switched to a professional group. He lives in a circle of people who understand him, who understand and help him. Who are silent when he needs silence and listen when he talks. Or when he plays the guitar and sings his favorite wistful songs…

Author: Ludmila Dobrovová, Moscow, Expressly for Stadión

Stadión, July 10, 1973, No. 28

Dohánět a předhánět

„Věřil si sám,” vykládal Günthard, “a to pro mne byl dostatečný́ důvod. Když jsem se ho ptal, jak je na tom s formou, byl sebejistý́. A to je u Viktora nanejvýš příznivé znamení, protože bývá — jak ho znám — velmi zdrženlivý́. Proto jsem si řekl, že Andrianov nemá ještě vyhráno.”

Švýcar může hovořit o sovětském borci takhle zasvěcené. Stál totiž náhodou u jednoho startu …

V roce 1962 byl Jacques Günthard na návštěvě v Moskvě. Bývalý vynikající závodník a již stejně výborný́ trenér — pod jeho dohledem cvičil i pozdější olympijský́ vítěz z Tokia Menicchelli — uměl vše dokonale vysvětlit a navíc to ještě uměl ukázat. Moskevským gymnastům předvedl svůj vrcholný́ prvek — přemet do stoje na bradlech. Po něm to zkoušeli ostatní. Günthard radil, opravoval, mluvil ústy i rukama. Zpovzdálí na něho kulili oči malí gymnastičtí kluci kteří se přikradli k instruktáži mistrů, a ukládali si do paměti každé slovo, každý́ pohyb. A třásli se nedočkavostí, aby si to všechno mohli už už vyzkoušet sami.

Jeden z nich, třináctiletý́ mrňous, napětí nevydržel. Zvedl ruku, ale ani pořádně nepočkal na dovolení a už se hrnul k nářadí. Naskočil, razantně nabral kmih a doslova vylétl do stoje na rukou, aby se tam zapíchl jako svíčka. Usměvavý́ trenér pokývl uznale hlavou a zavolal malého gymnastu k sobě.

„Jak se jmenuješ?”

„Viktor Klimenko.”

Viktor Klimenko — opakoval host pomalu, jako by si chtěl vrýt nové jméno do paměti. Pak se obrátil ke svým hostitelům: „Vzpomeňte si na má slova: z tohoto chlapečka bude jednou olympijský́ vítěz.”

Dědictví

U mimořádných osobnosti ve sportovní gymnastice, v tomto sportu kde se neoddělitelně kloubí obratnost a síla s houževnatostí a dravostí pod vrchním velením přísné kázně, je zvykem sáhnout do rodokmenů a pátrat, kde se tyto vlastnosti vzaly. U Viktora Klimenka to bylo velejednoduché. Gymnastou byl jeho otec i starší bratr. Ten jednoho dne odvedl s rodičovským požehnáním Viktora do tělocvičny. Tím byla dána náplň jeho klukovským dnům i směr pozdějšímu životu.

„Co bych byl pro bratříčka neudělal,” přiznává Michail. Sám byl talentovaný́ a pilný́, ale častá zranění přerušila jeho vlastní dráhu dříve, než se mohl vyšvihnout nahoru. „Viděl jsem v něm pokračování sama sebe. Lepší pokračování.”

Protože však sám ještě neměl dostatek trenérských zkušeností, doporučil brášku Vladislavu Brežnyěvovi, vynikajícímu pedagogu. Ten však záhy pochopil, že Klimenko mladší potřebuje růst pod vedením trenéra — fantasty, trenéra — experimentátora. A tím byl podle obecného mínění jedině Konstantin Karakašjanc.

Ovšem mezi seznámením učitele a žaka a vavříny pro Viktora Klimenka byla předlouhá šňůra dnů nepředstavitelného úsilí co nejprogresivnější koncepce sestav. Do nekonečna vymýšlel nové prvky, sestavoval z nich neobvyklé vazby a co hlavní, učil svého svěřence přemýšlet. Naučil Viktora nepřijímat nikdy nic slepě.

„Každý́ pohyb spojoval s výkladem zákonů mechaniky. Vzpomínám nesmírně rád na jeho tréninky, které byly doslova a do písmene učenými přednáškami. A vůbec mu nevadilo, že auditorium tvořím jen Já sám,” vykládá s vděčnosti Viktor.

Výskok na pódium

Ve sportovní gymnastice mužů je nemyslitelné „přijít, vidět, zvítězit”. Technikou cvičení se i nejnadanější prodírají jako pralesem a cestičkou, kterou si namáhavě prosekali, musejí znovu a znovu procházet sem a tam, aby nezarostla. Také sila, bezpodrnínečný předpoklad pro gymnastické disciplíny, přichází teprve lety. Nebylo a není tedy v tomto sportu mistra, který by na sebe neupozornil dávno předtím, než dostal na krk medaili s puncem světového zlata.

Ani Viktor Klimenko není výjimkou. Mimořádný byl však v tom, jak lehce chápal tajemství obtížných cviků. A v tom, že dokázal už při prvním vstupu na všesvazové mistrovství dorostu s převahou zvítězit. Jakmile se takto uplatnil v obrovské konkurenci sovětských závodníků, měl už bránu do světa pootevřenou. Otevřela se mu zcela za dva roky, kdy zvítězil na Spartakiádě národů v přeskoku. Osmnáctiletý Viktor Klimenko vstoupil do reprezentačního družstva SSSR. Za rok se — v předvečer mexické olympiády — obohatil o tři zlaté medaile mistra své země: za přeskok, prostná a koně našíř. V Mexiku pak obsadil sedmé místo v dvanáctíboji a přivezl si stříbro za úspěch družstva a bronz za svou sestavu na bradlech.

Úděl druhého

„Ne každému sportovci je dáno odolat po návratu z úspěšného olympijského klání svodům nečinnosti. Viktor byl jedním z mála. Hned po Mexiku začal znovu naplno trénovat, dokonce s ještě větším zaujetím než dříve. Jako by všechny medaile, do té doby získané, byly svědectvím porážky a nezdaru. Proč? Byl tady totiž kolega z družstva, dominující už několik let sovětské gymnastice — Michail Voronin.

Dohnat a předehnat, to je program těch, kteří se nespokojují s průměrem. Stal se i programem Viktora Klimenka. Dosud kralující mistr světa z. Dortmundu 1966 byl hmatatelným, živým mementem pro chvíle, kdy se Viktorovi zdálo, že už to dál nejde. Ne Nakajama, ne Kato, ne Kenmocu, ale gymnasta, jenž byl po ruce, jehož eleganci se mohl obdivovat a závidět mu ji, s kterým se mohl denně setkávat, jako se setkávají spolupracovníci v dílně a trávit s ním sváteční chvíle vzájemných střetnutí častěji než se vzdálenými Japonci.

Voronin však byl tuhý soupeř. Ne a ne podlehnout. Na mistrovství Evropy 1969 byl Viktor druhý. Nádherný úspěch! Ne ovšem uspokojivý, protože prvním byl Voronin. Na mistrovství SSSR 1970 získal Klimenko stříbrnou medaili, Voronin však zlatou. A také v Lublani téhož roku, kde už každý z expertů dával větší šance Viktorovi, dokázal ho ještě Michail při mistrovství světa svým čtvrtým místem o jednu příčku předběhnout.

Intermezzo

Vedla se v sovětské gymnastické rodině před — OH 1972 takováto diskuse:

— Máme u nás několik gymnastů, kteří sice nevynikají ve víceboji, ale předvádějí unikátní prvky na jednotlivých nářadích. Kdyby například Katkov z Moskvy byl zařazen do družstva, mohl by ve finálovém závodě v přeskoku zavadit o zlato.

— Základem gymnastiky je všestrannost, výkon ve víceboji, a bez toho se nikdo do finále nedostane. Sestavíme-li družstvo z klaunů, můžeme přijít i o naše tradičně druhé místo. Musíme spojovat jedno s druhým.

— Ani Japonci nemají nic mimořádně originálního a nového, jak jsme viděli nedávno při předolympijském turné v Japonsku. Zaměřují se na stabilitu provedení.

— Ano, to je pravda. Ovšem už před několika lety vytvořili japonští trenéři sestavy, o kterých se tehdy říkalo, že předběhly dobu. Oni však už tehdy mysleli na Mnichov a nechali si těch několik let, aby závodníci mohli získávat jistotu a brousit provedení. Teď jsou sice jejich sestavy známé, ale v Mnichově budou přesto nejprogresivnější a zároveň perfektně zacvičené. Až skončí tato olympiáda, budou se v Japonsku vymýšlet znovu nové věci.

— Také bychom potřebovali takovou perspektivnost. Dnes už můžeme dohonit Japonce co do obtížnosti, ale nezbývá nám čas na dokonalý nácvik.

— Japoncům tedy už půjde o olympijské hry 1976?

— O ně i o další. A nám by o ně mělo jít také.

Krok na slunce

Karakašjanc znovu prošpikoval již tak obtížné Viktorovy sestavy dalšími prvky nejvyšší obtížnosti. Podobaly se už akrobatickým výstupům. Když se poté, co byly vypilovány a vyblýskány, s nimi Klimenko představil přísným evropským rozhodčím, všichni pochopili, že toto je moderní pojetí sportovní gymnastiky. Prozíravé Karakašjancovo úsilí vydalo své plody.

Starostlivý sadař však už nesklízel ovoce společně se svým žákem. Přešel k vědecké a pedagogické práci na vysoké škole a Viktor se vrátil k tomu, jenž ho ke gymnastice přivedl, k svému bratru Michailovi. Oba se zatím stali mistry svého oboru, starší zasloužilým trenérem, mladší hvědou sovětské gymnastiky.

„Mnozí se obávali, že Miša nedokáže být ke mně tvrdý, jako byl Karakašjanc,“ vzpomíná Viktor. „K tomu vůbec nedošlo. Nelítostně trval na tom, že sestavy musí být Ještě náročnější, ale zároveň připomínal měkkost cvičení, efektní závěry a čistotu provedení.“

Do Madridu odjel Viktor na mistrovství Evropy 1971 spolu se svým největším rivalem. Pravda, neměl ještě Voroninovu eleganci, zato však ho předčil odvahou, originalitou, riskantností svého cvičení. A po zásluze poprvé vyhrál nad svým krajanem a vůbec nad celou evropskou elitou.

Pád a berle

Po radostné chvíli přišlo drama. Den poté, co uchopil do svých rukou evropský pohár, měl znovu projít po šesti stupních volného programu, kde se mělo rozhodnout o medailich za jednotlivé disciplíny. Klimenko nebyl ani tady bez šancí. Při rozcvičování na první z finálových závodů se však náhle po saltu zhroutil na koberec. V sále nastalo ticho, když na nosítkách odnášeli nového absolutního mistra Evropy.

Lékaři konstatovali přetržení achilovky. Po tomto zranění se jen málo sportovců dokázalo vrátit do velkého sportu. Neměl už ani Viktor Klimenko vstoupit na pódium? Měl to být konec jeho sportovní kariéry? Ve dvaadvaceti letech?

Klimenkova noha se dostala do rukou jednoho z nejlepších sportovních chirurgů, Vladimíra Baškirova, přednosty chirurgického oddělení První moskevské kliniky. Říká se, že Baškirov dokáže i nemožné. Dokázal. Kromě toho, že Viktorovi pomohl k úplné anatomické obnově tkání, vrátil mu i víru ve vlastní možnosti. Ještě na nemocničním lůžku se Klimenko rozhodl, že začne znovu.

Deset dnů po propuštění z nemocnice už bylo vidět Viktora Klimenka znovu v tělocvičně. Ještě s nohou v sádře a o berlích. Dva měsíce nato požádal, ano — doslova požádal, aby byl zařazen do družstva Moskvy a mohl závodit aspoň ve čtyřech disciplínách.

„Povolili ml to. Vím, že to bylo spíše ze soucitu, z přátelství, protože tehdy v můj návrat nikdo nevěřil,“ říká už bez hořkosti Viktor. „Bezvýhradně ml důvěřoval jen bratr Michail, manželka Larissa a doktor Baškirov. A samozřejmě Já sám sobě.“

Za osm měsíců po úrazu se Viktor začal dostávat do bývalé formy. Při obnovené premiéře v únoru 1972 cvičil ještě jakoby ostýchavě, ale už při mistrovství SSSR získal tři zlaté medaile. Dostal tedy plnou důvěru a hlavně místo v olympijském družstvu.

Vítězství, nejen účast

V Mnichově gymnasté poprvé bojovali čtyři namísto dřívějších tří dnů. To vyžadovalo mimořádnou fyzickou odolnost. V nejhorší situaci byl nesporně Viktor Klimenko. Jeho bratr a trenér Michail to věděl, a proto se snažil všemi prostředky obelstít přísné strážce olympijského pořádku a připlížit se k Viktorovi, aby mu namasíroval — ne zraněnou, ale zdravou nohu, která ho po zvýšené námaze bolela. Navíc mu praskl na dlani mozol. Banální gymnastické zranění, ale velice bolestivé, na které je jen jeden účinný lék — přestat cvičit. Což to bylo možné?

Než nastoupil Klimenko k finálovému boji na koni našíř, k boji s favorizovanými Japonci Katem a Kenmocuem, otevřel si sám polozahojenou ránu.

„Bylo to jediné řešení pro onen okamžik. Jinak bych byl musel aspoň podvědomě čekat, až mozol znovu praskne. Takhle mi nezbývalo, než se smířit s bolestí a mohl jsem na ni zapomenout,“ sportovci musejí umět být k sobě tvrdí.

Kůň našíř je zvláštní disciplína, která má svá vlastní kritéria. Železná vůle je při tomto cvičení neméně důležitá než fyzická síla a technika. Proto na tomto nářadí vyhrával tak často Boris Šachlin a Miroslav Cerar. Proto na něm vyhrál i Viktor Klimenko. Čtrnáct měsíců po svém zranění získal olympijské zlato, dokázal sílu svého charakteru. Do Mnichova totiž nejel jen s přáním být při tom, jel tam, aby zvítězil.

Repríza

Znovu však Klimenko nebyl první ve své vlasti. Sovětský „Japonec“ Nikolaj Andrianov se s mladistvou drzostí prodral na přední pozici a i v Mnichově se usadil na olympijském žebříčku hned za japonskou trojicí. Viktor měl znovu doma soupeře, který mu nedovolil ani po olympiádě odpočinout. Jen občas vyměnil tělocvičnu za tenisový kurt a gymnastice ukradl pár hodin pro svou další velkou lásku — kopanou. Nikdy mu sice ještě nejásaly vstříc tribuny fanoušků, ale očití svědkové tvrdí, že v něm mohla mít fotbalová sborná druhého Jevružichina. Mohla, ale nemá. Protože gymnastika svého Klimenka pořád ještě potřebuje.

Pro Jacka Gůntharda nebyl před letošním evropským šampionátem v Grenoblu jiný favorit…

Psalo se potom v komentářích, že jen na bradlech prokázal Viktor Klimenko svou supertěžkou sestavou jasně své prvenství. K absolutnímu titulu mu prý pomohl Andrianov svými chybami a chybičkami. Což však nepatří k prvenství i znalost taktiky, umění těžit ze zakolísání soupeře? Což si mistrovství nepodává ruku i se zralosti? Klimenko sklízí, co před lety zasel a po leta pěstuje. Proto ve čtyřiadvaceti letech je mu gymnastika stále ještě i budoucností.

Tím spíš, že už dnes — v plném rozkvětu svých sil — se promovaný pedagog Viktor Klimenko vydal ij na cestu gymnastické vědy. Téma jeho aspirantské práce zní: „Mimořádně obtížné závěry sestav cvičení na kruzích.“

Žije gymnastikou, žije s gymnastkou — Larissa, známá pod jménem Petriková, byla dlouholetou reprezentantkou SSSR, než přešla k profesionální skupině. Žije v kruhu lidí, kteří mu rozumí, kteří ho chápou a pomáhají mu. Kteří mlčí, když potřebuje ticho, a naslouchají, když povídá. Nebo když hraje na kytaru a zpívá své oblíbené zádumčivé písně…

More Interviews and Profiles